A Fried Pie and a Fish Dish: A Follow-Up

A year and a half ago I wrote in this blog about two snacks from Poland's northwestern city of Szczecin (pronounced SHCHEH-cheen). As I believed their Polish names to be utterly unpronounceable to English speakers, I referred to them as PS1 (pasztecik szczeciński, a kind of small machine-produced deep-fried pie) and PS2 (paprykarz szczeciński, a canned fish-and-vegetable spread). I wrote about the food of the Griffin City without ever having been there, using what written sources I could find.

Andrzej Szylar (pronounced AHND-zhey SHIH-lar), a chef who happens to hail from that city, was kind enough to comment on my post, providing some interesting additional information about the seasonings used in the original recipe for PS2. And in February of this year (before the pandemic had reached Poland) I finally visited Szczecin to take part, on Andrzej's invitation, in a culinary event called Night of Herring Eaters. I used the occasion not only to eat some herrings prepared in a myriad of ways, but also to finally sample the PS1. So now it's time to update that original post with new knowledge and new experiences.

I would like to, once again, thank Andrzej for the invitation, as well as express my gratitude to Ola Gawlikowska and Tomek Sroka for hosting me in Szczecin and showing me around the city.

A Fried Pie or a Doughnut?

Tomek showed me the way to the Pasztecik fast-food bar at 46, Polish Army Avenue (al. Wojska Polskiego 46), where the oldest Soviet-made PS1-frying machine in Szczecin is still operating. Inside the joint stood long tables decorated with vases plastered with stickers commemorating the bar's 50th birthday last year. It was late, the machine was already off, but there were still some PS1s left. I ordered two meatless ones, one with egg, the other with mushroom filling, and a plastic cup of hot borscht to wash them down.

What were they like? I had known that PS1s were made from deep-fried yeast-raised dough so they couldn't have been like the puff-pastry paszteciki I'm more familiar with. But I must admit I was still surprised by their fragrant spongy cake-like interior hidden beneath a very thin crunchy skin. In my opinion, their name, paszteciki or "little pies", is somewhat misleading. I would rather describe them as elongated savoury doughnuts.

And I think there's nothing more to add here. If you wish to sample this kind of doughnut, you have to go to Szczecin (even if it's a long way, I know).

A Szczecin Fish Dish with Nigerian Pepper

I've already written about the West African dish, allegedly called "chop-chop", which inspired the recipe for PS2. I've also written about "pima", the "very hot spice" that was commonly added to that dish, as well as about my suspicion that it nothing more than piment or chili pepper in French. But Andrzej added to this his own memories and conclusions which I would like to share with you:

| My father worked as a deep-sea fisherman at PPDiUR Gryf in Szczecin for thirty years. Ever since I remember, we've been using pima which I believed my father was bringing home from Africa. Pima looked like ground paprika, it was faded-reddish in colour and very hot. […] Having discussed it with my father, we came to the conclusion that the spice they were bringing from Africa was ground wild piri-piri, which they called "pima", Polonizing the Portuguese word "pimente". | ||||

— Andrzej Szylar, comments on Facebook, 24–29 November 2018, own translation

Original text:

|

Whether "pima" is a loanword from Portuguese or French (I'm going with the latter, for phonetic reasons), there's no doubt that it's a kind of chili pepper. All species of pepper belonging to the genus Capsicum, including bell peppers and chili peppers, come originally from the Americas. But when Columbus made his discoveries, the Europeans liked these peppers so much that they started to grow them everywhere they could. The Portuguese developed one of the hotter varieties and grew them throughout their vast empire, from Brazil, where it's still known as "pimenta malagueta", to Mozambique, from where it's spread all over Africa under the name "piri-piri".

But that's not all. In the original recipe for PS2 there was also another spice, which I haven't mentioned yet. This is what we can read in the official description of PS2 as a traditional product of West Pomerania:

| According to standard ZN-67/ZGR-09815 of 1 February 1987, paprykarz szczeciński [PS2] is a finely-ground paste made by combining the flesh of fish with rice, tomato paste, vegetable oil, onion, and seasoned with Nigerian pepper. | ||||

— Paprykarz szczeciński, in: Lista produktów tradycyjnych, Ministerstwo Rolnictwa i Rozwoju Wsi, 3 June 2018, own translation

Original text:

|

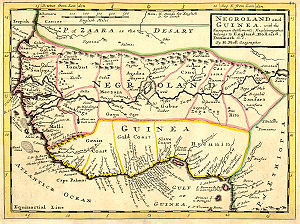

It's this "Nigerian pepper" that was a mystery to me for a long time. I had a few guesses about the exact identity of this spice, but couldn't settle on any of them. One of the suspects was Ashanti pepper (Piper guineense), also known as "West African pepper" or "Guinea pepper". Closely related to cubeb pepper, it was very popular in Medieval Europe, but is today largely marginalised to West Africa. Another possible candidate I was thinking of was grains of Selim (Xylopia aethiopica), a spice that taste similar to pepper and hence is known as "Ethiopian pepper", "Senegal pepper", "Guinea pepper", "African pepper" or even simply "Negro pepper". Could this latter name have been interpreted in Poland as "Nigerian pepper"?

When googling for "Nigerian pepper", most hits I got were for "Nigerian pepper soup", a traditional delicacy of that country. Contrary to its name, it isn't flavoured solely with pepper, but with an entire mix of various exotic spices that are hsrd to get outside Nigeria. This is how Andrzej described it:

| A black soup of game, fish, poultry and herbs is to this day the national dish of Guinea. Peppersoup is known and valued throughout Middle Africa, from the Gambia to Lagos, Nigeria. The soup exists in a lot of variants in Africa. It's the ancestor of the British pepper pot, an exceedingly peppery stew of mutton, honey and wine, seasoned with mint. Unlike the original, the British version is horrid. | ||||

— A. Szylar, op. cit., own translation

Original text:

|

So I thought that maybe "Nigerian pepper" didn't refer to a single spice, but to a whole mix. But was it made from? Well, [you can buy it on Amazon, which means you can also go there to read the list of ingredients:

- pepper;

- uda, that is, the aforementioned grains of Selim;

- uziza, or the likewise aforementioned Ashanti pepper;

- shuru, what that is I don't really know (pigeon pea, perhaps?);

- utazi, or ground dried leaves of Gongronema latifolium;

- ukazi, or dried leaves of African jointfir (Gnetum_africanum);

- Knorr powder.

But eventually it was Andrzej again who clarified all this by identifying "Nigerian pepper" as "Guinea pepper" (but not the same as Piper guineense), which is also known as grains of paradise:

| Nigerian pepper is most likely the same as Guinea pepper, also known as African pepper or grains of paradise. It has been, for a long time, appreciated by the Africans, who had learned to use it long before the hot pepper was brought from America. They used it to season their soups, sauces and other dishes of breathtaking pungency. Especially that the spice was first roasted for an even hotter flavour. […] Coming back to the paprykarz [PS2], the mysterious spice is probably a mixture of Guinean pepper and paprika. | ||||

— A. Szylar, op. cit., own translation

Original text:

|

It's a spice obtained from a plant which is more closely related to cardamon and ginger than to pepper and whose scientific name is Aframomum melegueta. Now, if you're thinking that "melegueta" sounds strangely familiar, then you're right. We've just talked about piri-piri, which is known as "''pimenta malagueta in Brazil. How come two quite unrelated spices have almost identical names? Well, for the same reason both Capsicum and Piper plants are called "pepper" in English. It's New World spices being named by Europeans after similarly pungent, but more familiar Old World spices. For centuries, many spices were not only used, but also named interchangeably.

And so, PS2, a Polish canned spread inspired by a Senegalese dish, but named after a Hungarian stew, was made from scraps of Atlantic fish, Bulgarian tomato pulp and seasoned with melegueta aka Guinea or Nigerian pepper, as well as with malagueta, introduced by the Portuguese from the Americas to Mozambique… It would be hard to find a more cosmopolitan food than this fish paste which only tastes good when you're hiking.

Herrings

Na koniec kilka słów o głównym powodzie mojej wyprawy do Szczecina. Noc Śledziożerców to wydarzenie cykliczne organizowane przez miłośników śledzi od co najmniej osiemnastu lat w miesiącach na literę L w restauracji Na Kuńcu Korytarza na Zamku Książąt Pomorskich. Format spotkania jest prosty: każdy z uczestników przynosi przygotowaną przez siebie potrawę ze śledzia, opowiada o niej kilka słów, a reszta słuchając degustuje. Nie ma ocen ani rankingu, jest za to kontemplacja pospolitej, ale przepysznej ryby, o której Tuwim pisał, że to „kawior ubogich, ust pokusa, bezsenne noce Lukullusa”.[1]

Ja w tym roku, w ostatni poniedziałek przed Wielkim Postem, a zarazem w moje urodziny, byłem tam po raz pierwszy w życiu (i żywię cichą nadzieję, że nie ostatni). Paluszki, pierogi, żurek (o nim już niedawno pisałem), czy deser – to tylko niektóre ze smakołyków, które mogłem tam skosztować. A to wszystko – ze śledziem w roli głównej! Dokładniejszą relację można przeczytać w szczecińskiej Wyborczej. Ja skupię się tu na tym, co sam przygotowałem.

Zrobiłem nie jedną, a dwie potrawy. Jedną była klasyczna sałatka śledziowo-ziemniaczana, którą nauczyłem się robić od Mamy. Ziemniaki, jabłko, czerwona fasola, czerwona cebula, ogórek kiszony, jajka na twardo, odrobina majonezu i musztardy… Jedynym udziwnieniem było użycie śledzi wędzonych. Danie może mało wykwintne, ale bardzo smaczne.

Drugim natomiast był kulinarno-historyczny eksperyment podobny do tego, który robiłem już kiedyś, gdy pisałem o prawdziwie staropolskim bigosie – bez kapusty i niekoniecznie z mięsem. Tym razem popełniłem więc bigosek śledziowo-agrestowy. Drobno pokrojone różowe śledzie, wymoczone najpierw w mleku, zamarynowałem w oleju z przyprawami (pieprz, ziele angielskie, goździki, kmin rzymski, gorczyca, kolendra, liść laurowy, koperek), a następnie połączyłem z agrestem duszonym na oliwie z cebulą, zielonym pieprzem, cukrem, cynamonem i gałką muszkatołową. Uważam, że eksperyment się całkiem udał i można go jeszcze powtórzyć.

A na koniec garść zdjęć innych śledziowych kreacji. Nie polecam oglądać na czczo!

References

- ↑ Julian Tuwim, Kwiaty polskie

| ◀️ Previous | 📜 List of posts | Next ▶️ |

| ⏮️ First | 🎲 Random post | Latest ⏭️ |