A Fried Pie and a Fish Dish: A Follow-Up

A year and a half ago I wrote on this blog about two snacks from Poland’s northwestern city of Szczecin🔊. As I believed their Polish names to be utterly unpronounceable to English speakers, I referred to them as PS1 (pasztecik szczeciński, a kind of small machine-produced deep-fried pie) and PS2 (paprykarz szczeciński, a canned fish-and-vegetable spread). I wrote about the food of the Griffin City without ever having been there, using what written sources I could find.

Andrzej Szylar🔊, a chef who happens to hail from that city, was kind enough to comment on my post, providing some interesting additional insight into the seasonings used in the original recipë for PS2. And in February of this year (before the pandemic had reached Poland) I finally visited Szczecin to take part, on Andrzej’s invitation, in a culinary event called Night of Herring Eaters. I used the occasion not only to eat some herrings prepared in myriad ways, but also to finally sample the PS1. So now it’s time to update that original post with new knowledge and new experiences.

I would like to, once again, thank Andrzej for the invitation, as well as express my gratitude to Ola Gawlikowska and Tomek Sroka for hosting me in Szczecin and showing me around the city.

A Fried Pie or a Doughnut?

Tomek showed me the way to the Pasztecik fast-food bar at 46, Polish Army Avenue (al. Wojska Polskiego 46), where the oldest Soviet-made PS1-frying machine in Szczecin is still operating. Inside the joint stood long tables decorated with vases plastered with stickers commemorating the bar’s 50th birthday last year. It was late, the machine was already off, but there were still some PS1s left. I ordered two meatless ones, one with egg, the other with mushroom filling, and a plastic cup of hot clear borscht to wash them down.

What were they like? I had known that PS1s were made from deep-fried yeast-raised dough so they couldn’t have been like the puff-pastry paszteciki I’m more familiar with. But I must admit I was still surprised by their fragrant spongy cake-like interior hidden beneath a very thin crispy skin. In my opinion, their name, “paszteciki” or “little pies”, is somewhat misleading. I would rather describe them as elongated savoury doughnuts.

And I think there’s nothing more to add here. If you wish to sample this kind of doughnut, you have to go to Szczecin (even if it’s a long way, I know).

A Szczecin Fish Dish with Nigerian Pepper

I’ve already written about the West African dish, allegedly called “chop-chop”, which inspired the recipë for PS2. I’ve also written about “pima”, the “very hot spice” that was commonly added to that dish, as well as about my suspicion that it was really nothing more than piment or chili pepper in French. But Andrzej added to this his own memories and conclusions which I would like to share with you:

| My father worked as a deep-sea fisherman at PPDiUR Gryf in Szczecin for thirty years. Ever since I can remember, we’ve been using pima which I believed my father was bringing home from Africa. Pima looked like ground paprika, it was faded-reddish in colour and very hot. […] Having discussed it with my father, we came to the conclusion that the spice they were bringing from Africa was ground wild piri-piri, which they called “pima”, Polonizing the Portuguese word “pimente”. | ||||

— Andrzej Szylar, comments on Facebook, 24–29 November 2018, own translation

Original text:

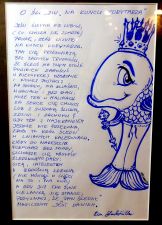

|

Whether “pima” is a loanword from Portuguese or French (I’m going with the latter, for phonetic reasons), there’s no doubt that it’s a kind of chili pepper. All species of pepper belonging to the genus Capsicum, including bell peppers and chili peppers, come originally from the Americas. But once Columbus had made his discoveries, the Europeans found these peppers so appealing that they started to grow them wherever they could. The Portuguese developed one of the hotter varieties and grew them throughout their vast empire, from Brazil, where it’s still known as “pimenta malagueta”, to Mozambique, from where it’s spread all over Africa under the name “piri-piri”.

But that’s not all. In the original recipë for PS2 there was also another spice, which I haven’t mentioned yet. This is what we can read in the official description of PS2 as a traditional product of West Pomerania:

| According to standard ZN-67/ZGR-09815 of 1 February 1987, paprykarz szczeciński [PS2] is a finely-ground paste made by combining the flesh of fish with rice, tomato paste, vegetable oil, onion, and seasoned with Nigerian pepper. | ||||

— Paprykarz szczeciński, in: Lista produktów tradycyjnych, Ministerstwo Rolnictwa i Rozwoju Wsi, 3 June 2018, own translation

Original text:

|

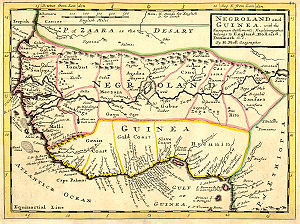

It’s this “Nigerian pepper” that was a mystery to me for a long time. I had a few guesses about the exact identity of this spice, but couldn’t settle on any of them. One of the suspects was Ashanti pepper (Piper guineense), also known as “West African pepper” or “Guinea pepper”. Closely related to cubeb pepper, it was very popular in Medieval Europe, but is today largely marginalised to West Africa. Another possible candidate I was thinking of was grains of Selim (Xylopia aethiopica), a spice that tastes similar to pepper and hence is known as “Ethiopian pepper”, “Senegal pepper”, “Guinea pepper”, “African pepper” or even simply “Negro pepper”. Could this latter name have been interpreted in Poland as “Nigerian pepper”?

When googling for “Nigerian pepper”, most hits I got were for “Nigerian pepper soup”, a traditional delicacy of that country. Contrary to its name, it isn’t flavoured solely with pepper, but with an entire mix of various exotic spices that are hard to get outside Nigeria. This is how Andrzej described it:

| A black soup of game, fish, poultry and herbs is to this day the national dish of Guinea. Peppersoup is known and valued throughout Middle Africa, from the Gambia to Lagos, Nigeria. The soup exists in a lot of variants in Africa. It’s the ancestor of the British pepper pot, an exceedingly peppery stew of mutton, honey and wine, seasoned with mint. Unlike the original, the British version is horrid. | ||||

— A. Szylar, op. cit., own translation

Original text:

|

So I thought that maybe “Nigerian pepper” didn’t refer to a single spice, but to a whole mix. A mix of what exactly, though? Well, you can buy it on Amazon, which means you can also go there to read the list of ingredients:

- pepper;

- uda, that is, the aforementioned grains of Selim;

- uziza, or the likewise aforementioned Ashanti pepper;

- shuru, what that is I don’t really know (pigeon pea, perhaps?);

- utazi, or ground dried leaves of Gongronema latifolium;

- ukazi, or dried leaves of African jointfir (Gnetum africanum);

- Knorr powder.

But eventually it was Andrzej again who clarified all this by identifying “Nigerian pepper” as “Guinea pepper” (but not the same as Piper guineense), which is also known as grains of paradise:

| Nigerian pepper is most likely the same as Guinea pepper, also known as African pepper or grains of paradise. It has been, for a long time, appreciated by the Africans, who had learned to use it long before the hot pepper was brought from the Americas. They used it to season their soups, sauces and other dishes of breathtaking pungency. Especially that the spice was first roasted for an even hotter flavour. […] Coming back to the paprykarz [PS2], the mysterious spice is probably a mixture of Guinea pepper and paprika. | ||||

— A. Szylar, op. cit., own translation

Original text:

|

It’s a spice obtained from a plant which is more closely related to cardamon and ginger than to pepper and whose scientific name is Aframomum melegueta. Now, if you’re thinking that “melegueta” sounds strangely familiar, then you’re right. We’ve just talked about piri-piri, which is known as “pimenta malagueta” in Brazil. How come two quite unrelated spices have almost identical names? Well, for the same reason both Capsicum and Piper plants are called “pepper” in English. It’s New World spices being named by Europeans after similarly pungent, but more familiar Old World spices. For centuries, many spices were not only used, but also named interchangeably.

And so, PS2, a Polish canned spread inspired by a Senegalese dish, but named after a Hungarian stew, was made from scraps of Atlantic fish, Bulgarian tomato pulp and seasoned with melegueta a.k.a. Guinea or Nigerian pepper, as well as with malagueta, introduced by the Portuguese from the Americas to Mozambique… It would be hard to find a more cosmopolitan food than this fish paste, which somehow only tastes good when you’re spending your time outdoors.

Herrings

And for the encore a few words about the main reason for my first-ever trip to Szczecin. The Night of Herring Eaters (Noc Śledziożerców) is an event that has been held three times a year (on the months whose Polish names start with an L, that is, February, July and November) for at least eighteen years at Na Kuńcu Korytarza restaurant in the old castle of the dukes of West Pomerania. It’s basically a potluck supper where each participant brings his or her own herring dish and says a few words about it while others listen and eat. There’s no grading or ranking, just contemplation of the unassuming but delicious silvery fish.

My first (and, hopefully, not the last) time there was on the last Monday before this year’s Lent, which also happened to be my birthday. Bread sticks, dumplings, sour rye-meal soup (already mentioned in my last post), a dessert – these are just a few of the delicacies, all featuring herring, I could sample there. But let me focus on what I brought to the table.

I made not one, but two dishes. One of them was a classic potato-and-herring salad I’ve learned to make from my Mom. Potatoes, apples, red beans, red onions, dill pickles, hard-boiled eggs, a dollop of mayo and mustard… The only departure from the original recipë was that I used smoked herrings. This may not be a very refined dish, but it’s a very tasty one.

The other concoction was more in the realm of historical reënactment, similar to what I once did when writing about genuine Old Polish bigos (without sauerkraut or meat). This time it was a herring-and-gooseberry bigos. I used salted pink herrings, which I soaked in milk before chopping them up and marinating in vegetable oil with a selection of spices (black pepper, allspice, cloves, cumin, mustard seeds, coriander, bay leaves, dill, all ground in a mortar). Then I combined them with gooseberries stewed in olive oil with onions, green peppercorns, sugar, cinnamon and nutmeg. I’m convinced the experiment was a successful one and may be repeated in the future.

And here’s a handful of photos of other herring-based delights. I wouldn’t recommend viewing them on an empty stomach!

| ◀️ Previous | 📜 List of posts | Next ▶️ |

| ⏮️ First | 🎲 Random post | Latest ⏭️ |