Epic Cooking: Supper in the Castle

Epic Cooking Food and Drink in “Pan Tadeusz”, the Polish National Epic |

Epic Cooking

Food and Drink in “Pan Tadeusz”,

the Polish National Epic

This is another post in a series about food in Pan Tadeusz, the Polish national epic by Adam Mickiewicz. While wandering around Europe after his exile from Poland, Mickiewicz always kept in his traveling library an "old, worn cookbook", which he would read from time to time "with great pleasure", hoping to one day give a "truly Polish-Lithuanian banquet" according to "the ancient recipes".[1] I will write about the title of this book in a different post. For now, it suffices to say that the poet never had the occasion to fulfil his dream of hosting a real-life Old Polish-Lithuanian feast and had to satisfy his culinary fantasies by conjuring up a perfect traditional banquet on the pages of Pan Tadeusz instead.

He placed his description of an old-fashioned "Polish dinner" in the books (chapters) XI and XII of the poem. In the earlier books, on the other hand, we can find depictions of the kind of meals the author could remember from his own youth in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania (a constituent nation of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, which covered not only the territory of the modern-day Republic of Lithuania, but also the much larger Belarus). For him, these were just the ordinary, daily fare of the "land of [his] childhood". For us, though, it is what the cookery described in his treasured little book was to Mickiewicz – the forgotten world Old Polish cuisine. And just like Mickiewicz would fantasize about recreating an Old Polish banquet, so would I like to share with you my own vision of a Pan Tadeusz-style supper. Someone someday may actually try to prepare a meal based on the menu I propose here; but for now let's stick mostly to our imagination.

“They Supped Inside the Castle”

This and next frames come from Andrzej Wajda's 1999 film adaptation of Pan Tadeusz.

I already wrote about the chronology of the meals described in Pan Tadeusz in my post about the epic's breakfasts. As you may or may not remember, there are three afternoon or evening meals described in the first five book of the poem. These include a Friday supper in the ruined castle of the Horeszko family, a Saturday dinner at Judge Soplica's manor house and a Sunday supper held in the castle again. We'll try and use the poet's descriptions of all three meals to piece together our menu.

They supped inside the castle. Protase, no permission, | ||||||

— Adam Mickiewicz: Pan Tadeusz, or The Last Foray in Lithuania: A Tale of the Gentry during 1811–1812, translated by Marcel Weyland, Book V, verses 305–308

Original text:

|

But why did Protase, a former court usher, insist on having the supper in the murky ruins of an abandoned castle? Officially, because the castle, more spacious than Judge Soplica's house, could better accommodate the many guests who arrived for the conclusion of the court case between the Judge and the Count. But as the castle was what the whole litigation was actually about, it was Protase's idea to prove that the Judge had gained ownership of the ruins through usucaption. In other words, the castle is his, because dines in it.

First Course

As you may know, the main meal of the day in Poland begins invariably with soup. It was no different in Soplica's house, except that, just before the soup, the men were served a small apéritif.

The guests entered in order and stood for the grace: | ||||

— Mickiewicz, op. cit., Book I, verses 300–307 (M. Weyland's translation with modifications)

Original text:

|

The Poles have known for a long time that there's nothing better than vodka to open a meal, but the West is only now beginning to discover clear vodka as the perfect apéritif. This is how two East Europeans living in the West, Nicholas Ermochkine and Peter Iglikowski, described it in their book:

| There is a long tradition confirming vodka's vocation as an ideal aperitif. The custom at the banquets of Polish and Russian nobility was to offer male guests vodka before serving fine wines and quality ales for the remainder of the feast. […]

The function of a good aperitif is not just to whet the appetite, but to get people in the right mood for what follows. Champagne is a very good aperitif for this purpose, but vodka is even better. […] Two glasses of vodka can […] give a wholly unimagined dimension to the most tiring in-laws in record breaking time. If you want to get the evening off to a good start, then vodka as an aperitif is probably unbeatable. |

| — Nicholas Ermochkine, Peter Iglikowski: 40 Degrees East: An Anatomy of Vodka, New York: Nova Science Publishers, 2003, p. 24–25 |

Why was it only for men, though? Why didn't the women get any vodka? After all, already in the 18th century, did the Rev. Jędrzej Kitowicz write of noble ladies that the "often got drunk on vodka".[3] Or maybe that's precisely why?

So this what the first course looked like on the first day. Was it any different on the second day?

The guests entered in order and stood for the grace: | ||||

— Mickiewicz, op. cit., Book III, verses 712–719 (M. Weyland's translation with modifications)

Original text:

|

On the third day, the supper started according to the same scheme again, although with some slight modifications:

The guests entered in order and stood for the grace: | ||||

— Mickiewicz, op. cit., Book V, verses 309–318 (M. Weyland's translation with modifications)

Original text:

|

This ritual repetitiveness of Soplica's meals was adjusted only to the season and to the Catholic calendar of feasts and fasts. In this case, it's Lithuanian cold borscht, a summertime soup that is still as popular in both Lithuania and Poland as gazpacho is in Spain.

There is a linguistic problem here, though. Mickiewicz has used two different terms, "chłodnik" (pronounced WHAWD-neek) and "chołodziec" (haw-WAW-jets). Both words derive from the adjective "chłodny", or "cold", but while Mickiewiczologists have no doubt that "chłodnik" refers to a cold soup, there is some disagreement as to what kind of dish chołodziec was.[4] Is it a regional name for the same soup or an aspic dish? After all, the Russian word "холодец" (kholodets) refers to meat-based jelly. It's possible that this term had filtered into the eastern dialects of Polish. Besides, veal feet in jelly would have paired perfectly with the vodka.

On the other hand, the vodka was served to men only, but the chołodziec was consumed by all. What's more, there's no evidence that, in the 19th century, the word was used for aspic anywhere outside certain regions of Russia proper; it's not attested in either Polish or Belarusian of the time (of course, aspic dishes themselves had been known since the Middle Ages, albeit under other names). And any way, the oldest translations of Pan Tadeusz into both Russian and Belarusian render both "chłodnik" and "chołodziec" as soup. It looks like both Mickiewicz himself and his contemporary translators had no doubts that these two words were synonyms.

There's another interesting difference, though. On the third day, the cold borscht was "whitened", or clouded with sour cream, but on the first and second days, it wasn't. Why? One possible explanation would be that the first two days were Friday and Saturday, that is, fasting days. In Polish tradition, dairy products were proscribed on fasting days along as well as meat. It was only on Sunday that the same cold borscht was served again, but this time, enhanced with the luxurious additive. Except that if the Soplicas fasted on Saturday, then they must have done it only in the afternoon, because for breakfast they'd had not only cream, but even smoked goose breasts, beef tongues, ham and steaks! This may be explained away only by the poet's inconsistency.

Sp how do you prepared this whitened Lithuanian cold borscht? Here's a recipe from The Lithuanian Cook, a Polish-language cookbook by Wincentyna Zawadzka. The first edition was published two decades after Mickiewicz had penned Pan Tadeusz, but I suppose the recipe would have been quite similar in his times. Heck, even today Lithuanian cold borscht is still made in pretty much the same fashion.

| Grind a large handful of chopped fresh dill with salt. Cook some chopped sorrel, chards or red beetroots and leave to cool down. Add some meat broth, half a gallon of sour cream, mix it all together and adjust the thickness and sourness by adding more broth or cream, so that the soup is white and cloudy. Just before serving, add a few chunks of ice, a few quartered hard-boiled eggs, a few finely chopped cucumbers, threescore crayfish tails or some large cooked fish, or if you don't have any, some roasted veal cut into thin stripes. If you have cauliflower or asparagus, then you can some that was boiled separately in water, cooled down and broken into chunks. | ||||

— [Wincentyna Zawadzka]: Kucharka litewska, Wilno: nakładem autorki, 1860, p. 29, own translation

Original text:

|

Second Course

Now that we know what they had for soup, let's find out what was served as the second course.

Next came crayfish and chicken, asparagus stalks, | ||||

— Mickiewicz, op. cit., Book V, verses 319–320 (M. Weyland's translation with modifications)

Original text:

|

And here we've got another puzzle which Mickiewiczologists have been trying to figure out for decades. Crayfish was easily available in late summer, chicken possibly too, but asparagus? The season for asparagus is in May, right? So how could it find itself on the table next to the late-summer crayfish? Was it only for the rhyme? Or is this yet another of the poet's mistakes who seems to have juggled the seasons quite liberally in his work?

| In this paradise, springtime flowers are in bloom alongside ripening autumn fruits. At the same time, violets and Michaelmas daisies grace some perfect season, in which poppies charm they eye with a "multi-hued show", in which the pumpkin ripens, farmers harvest grain and cut down grass, and the feast of Our Lady of Herbs falls on Palm Sunday. | ||||

— Julian Przyboś: Czytając Mickiewicza, Warszawa: Państwowy Instytut Wydawniczy, 1965; cyt. w: Halina Szymanderska: Sekret kucharski, czyli co jadano w Soplicowie, Warszawa: Prószyński i S-ka, 1999, p. 6; cyt. w: Agnieszka M. Bąbel: Garnek i księga – związki tekstu kulinarnego z tekstem literackim w literaturze polskiej XIX wieku, in: Teksty Drugie: Teoria literatury, krytyka, interpretacja, 6, Warszawa: Instytut Badań Literackich Polskiej Akademii Nauk, 2000, p. 164, own translation

Original text:

|

"Disturbed, shaken, uncertain," we begin to doubt the realism of the epic's setting. But no, "such master errs not!"[5] It's perfectly possible to defend the presence of asparagus in early September. After all, the poet didn't specify that it was fresh asparagus. And the art of pickling asparagus had been known in Poland for ages. Here's a recipe for vinegar-pickled asparagus from a 17th-century herbal writting by a famous Polish Renaissance botanist, Prof. Simon Syrenius (Szymon Syreński):

| Take fresh [asparagus] sprouts, spread them in bowls, sprinkle with salt and leave in the shade for two days, then douse them with the liquid they emit. And should they not exude any moisture, then wash them in brine and press down with a weight, then put them in a glazed pot, cover well with two parts wine vinegar and one part brine, adding a generous amount of fennel. This way, all year long you may have a fine delicacy on your table. | ||||

— Simon Syrennius: Zielnik, Kraków: 1613, p. 1128–1129, own translation

Original text:

|

Very well, but how do you combine these pickles with chicken and crayfish into one dish? Let's consult The Lithuanian Cook once again. We can find there a recipe for "chicken with mayonnaise", elegantly garnished with, that's right, asparagus and crayfish (and cauliflower to boot).

| Put whole young, well-fattenned chickens into vegetable broth, along with a spoonful of butter, a chunk of beef or pork and cook under cover. Once they are soft, retrieve them, let cool, cut into pieces and remove the skin. Arrange them on a platter, dress with mayonnaise and garnish with cooked asparagus, cauliflower, crayfish tails (which should have been first bathed in vinegar with olive oil) and serve with a cold sauce of hard-boiled yolks ground with sugar, vinegar and olive oil. | ||||

— Zawadzka, op. cit., p. 195, own translation

Original text:

|

Naturally, if you use pickled asparagus, then don't add too much vinegar into this dish. This quite sour course would have been paired with sweet Malaga wine. And if we've got too much asparagus and crayfish, then we may also add them to our cold borscht, as could see in the recipe for the first-course dish.

Third Course

After the second course, it's time for the third. What does the poet tell us about it?

The third course had been served. And then Lord Chamberlain, | ||||

— Mickiewicz, op. cit., Book I, verses 332–336

Original text:

|

So, not much. All we know that cucumbers were served on the side. But what about the meat? We're going to have to complete the picture with our own imagination. After a rather light poultry course, I suppose it's time for something more substantial. And as August and September are mutton season, then why not some ram meat? Let's take the first recipe for mutton that we can find in The Lithuanian Cook:

| Marinate a large mutton roast for a few days in vinegar that has been boiled with spices; remove, press out the liquid, lard with pork fatback and stew on low heat in a saucepan, along with chopped onion, fatback, a few juniper berries, various soup greens and a glass of bouillon or wine. Serve with strong bouillon-based gravy mixed with strained roast drippings and seasoned with lemon, capers or olives. | ||||

— Zawadzka, op. cit., p. 105–106, own translation

Original text:

|

And, from the same book, a recipe for "stewed cucumbers for serving with mutton":

| Take a few or more fresh cucumbers, peel, cut lenghtwise, salt and leave for half an hour. Melt a spoonful of butter, sauté a finely chopped onion in it, mix in the cucumbers and stew them until soft. Finally, sprinkle the cucumbers with flour, stew some more, douse with some good bouillon, bring to boil and, when serving, use them as a garnish for the meat. | ||||

— Zawadzka, op. cit., p. 62, own translation

Original text:

|

Early September may be somewhat late for fresh cucumbers, but we do know that Sophie picked them with her own hand in her little garden.

Near the fence long mounds, convex, with greenery filled, | ||||

— Mickiewicz, op. cit., Book II, verses 430–435

Original text:

|

But even if cucumbers were no longer in season, Zawadzka assures us that "brine-pickled cucumbers may be stewed in the same way".[6] And so, we've got another course that is both greasy and sour. Fat mutton marinated in vinegar, pickled cukes and all of it stewed in lard or butter. This will be accompanied with Hungarian Tokay wine.

Czwarte danie

[…] with the fourth course, |

| — Mickiewicz, op. cit., Book I, verses 537–538 |

Zaraz, czwarte danie? To ileż było tych dań? Ano minimum cztery. W tym, co dziś uznajemy za tradycyjną kuchnię polską, obiad dwudaniowy to norma, ale w XIXnbsp;w. wystawny obiad nie miewał mniej niż cztery dania, nie licząc deseru.

Niestety o czwartej potrawie na wieczerzy u Sędziego Soplicy wiemy tylko tyle, że jakaś była. Jej opisu poeta nie podał. Mamy za to opis wielkiej pijackiej awantury, która rozpętała się podczas drugiej wieczerzy na zamku. W ruch poszły wtedy kielichy, butelki, noże, ławy, a nawet piszczałki organowe. Gdy wszystko już ucichło, na miejscu uczty pozostało pobojowisko i… resztki jedzenia. Może z tych resztek uda nam się wyczytać coś na temat potraw podanych pod koniec posiłku?

No loss there of life human, but benches and chairs | ||||

— Mickiewicz, op. cit., Book V, verses 793–810

Original text:

|

Wygląda na to, że pod koniec kolacji na stół wrócił drób, w tym indyki. Te ostatnie, choć pochodzą z Ameryki, zadomowiły się w Polsce dość szybko po podróżach Kolumba, spychając ze stołów inne duże ptaki, jak pawie i łabędzie, które odtąd hodowano już głównie jako ptaki ozdobne. W XIXnbsp;w. pieczony indyk był już od dawna uważany za staropolski przysmak.

Indyki, kury i inny drób, jak kaczki, gęsi, gołębie, hodowała w Soplicowie wybitna specjalistka, pani ochmistrzyni,…

[…]a lady of fame, | ||||

— Mickiewicz, op. cit., Book III, verses 28–36

Original text:

|

Pomagała jej w tym Zosia, nieco nadgorliwie tucząc ptactwo „perłowemi krupy”.[7]

Zosia, dressed for the morning, and with her head bare, | ||||

— Mickiewicz, op. cit., Book V, verses 55–84

Original text:

|

Jak takiego wypasionego na pańskich krupach indyka można było przyrządzić? Kurczęta na drugie danie były gotowane, więc indyka zróbmy pieczonego.

| Oskubać i oprawić młode indyki, i zostawić tak na parę dni na zimnie aby skruszały; naszpikować, posolić trochę, obwinąć papierem i piec na rożnie, polewając masłem; skoro będą prawie gotowe, odjąć papier i polewać beszamelem, a gdy nabierze złotawego koloru, zdjąć ostrożnie z rożna aby nie opadł. Beszamel tak się urządza: rozpuścić kawałek masła, wsypać łyżkę mąki, rozmieszać, rozprowadzić półkwartą świeżego mleka lub śmietanki, wbić trzy żółtka i zagotować to mocno, mieszając […] |

| — Zawadzka, op. cit., s. 123 |

A do picia – szampan, który, co ciekawe, w Panu Tadeuszu pojawia się niemal równie często jak węgrzyn.

Deser

O wetach, czyli deserach, podczas Soplicowskich posiłków nie wiemy nic. Większość posiłków opisanych w poemacie zostaje w taki czy inny sposób przerwanych, zanim służba zdążyła podać deser. Z potraw deserowych wzmiankowany jest w Panu Tadeuszu jedynie kisiel, a i to tylko w przysłowiu.

And why, out of the woodwork, did this Count appear? | ||||

— Mickiewicz, op. cit., Book VI, verses 169–171 ***

Original text:

|

Co ciekawe, poeta najwyraźniej uznał że słowo „kisiel” może być nieznane Polakom spoza Litwy, dodał więc objaśniający je przypis:

| Kisiel, potrawa litewska, rodzaj galarety, która się robi z rozczynu owsianego; płócze [sic] się wodą, aż póki nie oddzielą się wszystkie cząstki mączne. Stąd przysłowie. |

| — Mickiewicz, op. cit., Objaśnienia |

Tak naprawdę, kisiel to jedna z najbardziej starożytnych słowiańskich potraw. Z tym że oryginalnie kisiel nie był wcale słodki, lecz kwaśny. Samo słowo „kisiel” oznacza przecież coś, co się ukisiło. W swojej pierwotnej wersji była to biała glutowata galareta przypominająca zakwas na żur. Robiło się ją tak, że otręby owsiane czy żytnie płukało się wielokrotnie, jak to opisał Mickiewicz, a uzyskaną w ten sposób zawiesinę zostawiało się, aż sfermentuje i skrzepnie na tyle, że można ją kroić nożem. I to, proszę Państwa, był dla naszych słowiańskich przodków prawdziwy przysmak. Mieszkańcy dawnej Rusi, jak możemy przeczytać w starych wschodniosłowiańskich baśniach, krainę wiecznej szczęśliwości wyobrażali sobie jako rzekę mleka płynącą pośród kisielowych brzegów. Zresztą pewnie tak właśnie – z mlekiem – ów kisiel podawano. Powieść minionych lat, XII-wieczna kronika Rusi Kijowskiej, podaje też legendę o tym, jak kisiel uratował miasto Biełgorod od oblężenia przez Pieczyngów. A było to tak: pewien biełgorodzki staruszek wpadł podczas oblężenia na pomysł, aby wykopać wielki dół, zalać go owsianym krochmalem i poczekać, aż skiśnie. Następnie do grodu zaproszono pieczyńskich wysłanników, żeby pokazać im ów dół z kisielem, poczęstować ich i wreszcie przekonać, że głodem ich nie zmorzą, bo to sama święta ziemia biełgorodzian karmi, w związku z czym dalsze oblężenie jest bezcelowe i najlepiej, żeby Pieczyngowie spokojnie wrócili sobie na step, z którego przyjechali.[8]

Widać, że nie tylko Polacy, jak twierdził Łukasz Gołębiowski, jeden z pierwszych polskich etnografów, ale Słowianie w ogóle „lubili i lubią […] kwaśne potrawy, ich krajowi poniekąd właściwe i zdrowiu ich potrzebne.”[9] Ale niewątpliwie już dawno bywali i tacy, co próbowali przeraźliwą kwaśność kisielu w jakiś sposób osłodzić – czy to miodem, czy owocami. I tak z czasem kisiel wyewoluował w potrawę słodką. Na koniec – już w XIXnbsp;w. – mączkę z otręb owsianych zastąpiono skrobią ziemniaczaną i tak narodził się kisiel, który znamy dzisiaj. Poniższy przepis na „kisielek jabłeczny”, wzięty również z książki Zawadzkiej, to już bardziej współczesna wersja, zawierająca „mąkę kartoflaną” i cukier, i niewymagająca kiszenia.

| Obrać jabłka, pokroić, rozgotować w wodzie, przecedzić przez sito. Zaprawić cynamonem i cukrem, dolać tyle wody, aby było tej masy szklanek sześć, rozprowadzić częścią jej szklankę kartoflowej mąki; resztę zagotować, do wrzącego wlać rozwiedzioną mąkę, wybijając kilka minut łyżką na ogniu. Formę namoczyć wodą, wysypać cukrem, wlać kisiel i postawić na zimnie. |

| — Zawadzka, op. cit., s. 422 |

A żeby deser nieco urozmaicić i wykorzystać inne jesienne owoce, to dorzucam jeszcze, z tego samego źródła, przepis na kompot z gruszek. Z tym że XIX-wieczne kompoty to nie mocno rozwodnione napoje, jakie znamy dzisiaj, ale gęste, bardzo słodkie syropy. Właściwie to równie dobrze można kupić puszkę gruszek w syropie, przelać zawartość do salaterek, dodać przypraw i efekt będzie pewnie ten sam.

Przepis na kompot z gruszek:

| Wziąć kilkanaście niewielkich [gruszek], obrać z łupiny, nakroić karbowanym nożem, wydrylować środek, wrzucić do gorącej wody zaprawionej cukrem, cynamonem w kawałkach i goździkami. Skoro [gruszki] będą miękkie, wybrać przez sito, płyn przecedzić, wygotować do niewielkiej ilości, dodać pół funta cukru, […] cytrynę pokrajaną w talerzyki [t.j. w plasterki] bez pestek, wysadzić ulep do gęstości i zalać nim ułożone w salaterce [gruszki]. Jeżeli [gruszki] są duże, to krają się na cząstki. |

| — Zawadzka, op. cit., s. 419–420 |

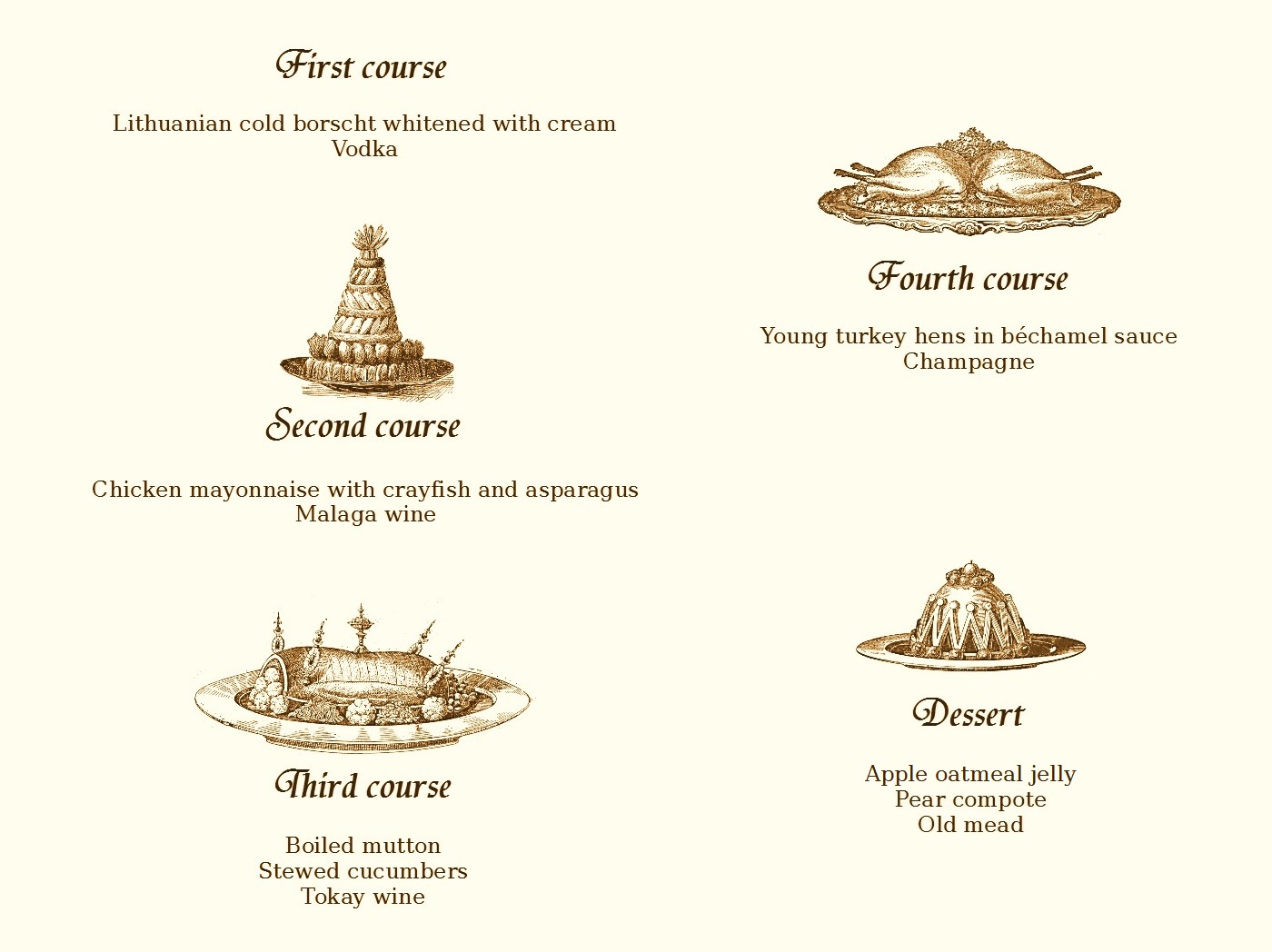

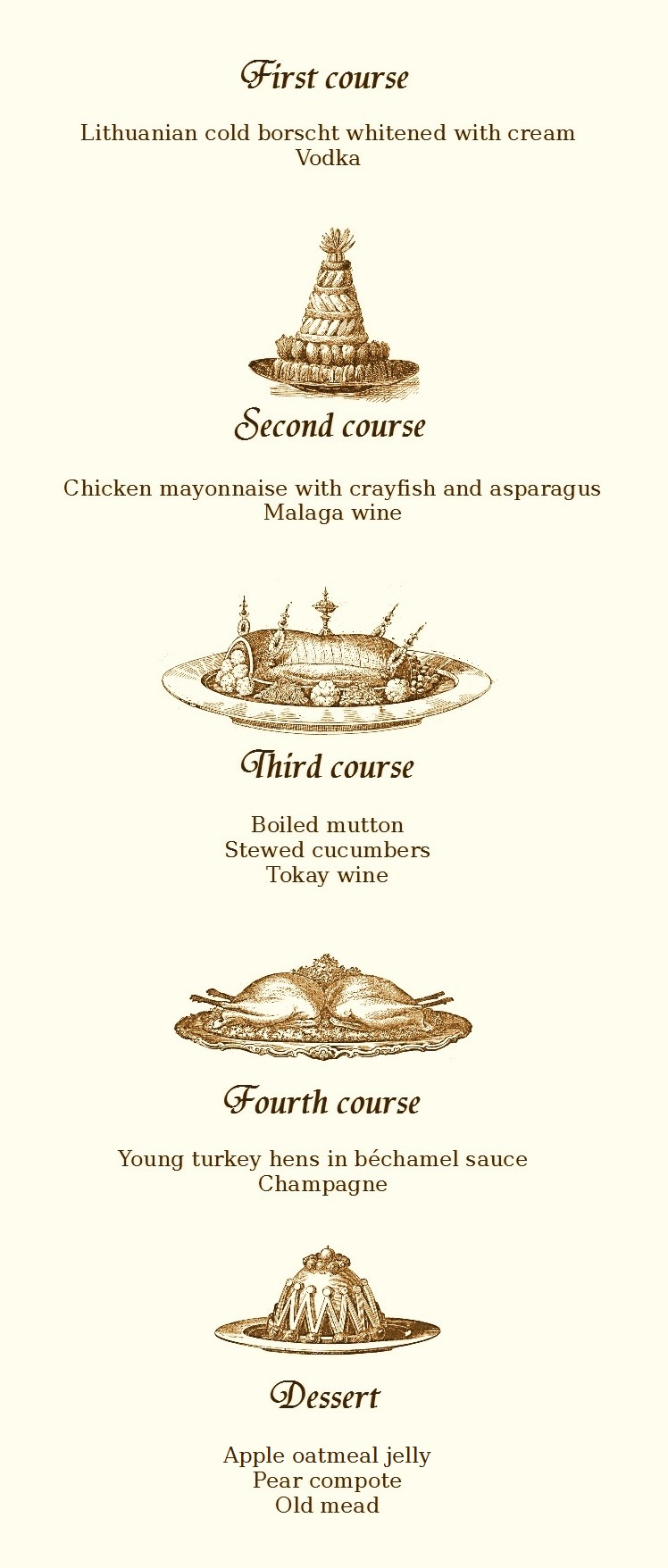

I tak oto skompletowaliśmy cały jadłospis uczty w stylu soplicowskim:

References

- ↑ Excerpts quoted from a letter by Antoni Edward Odyniec, Mickiewicz's travel companion, dated 28 April 1830, quoted in: Izabela Jarosińska: Kuchnia polska i romantyczna, Kraków: 1994, p. 206; quoted in: Agnieszka M. Bąbel: Garnek i księga – związki tekstu kulinarnego z tekstem literackim w literaturze polskiej XIX wieku, in: Teksty Drugie: Teoria literatury, krytyka, interpretacja, 6, Warszawa: Instytut Badań Literackich Polskiej Akademii Nauk, 2000, p. 165

- ↑ Adam Mickiewicz: Pan Tadeusz, or The Last Foray in Lithuania: A Tale of the Gentry during 1811–1812, translated by Marcel Weyland, Book I, verses 262–263

- ↑ Jędrzej Kitowicz: O trunkach, in: Opis obyczajów i zwyczajów za panowania Augusta III, Poznań: 1840, p. 211–212

- ↑ Maria Frankowska: Chołodziec, poezja i piernik, in: Pamiętnik Literacki: czasopismo kwartalne poświęcone historii i krytyce literatury polskiej, 87/1, Warszawa: Instytut Badań Literackich Polskiej Akademii Nauk, 1996, p. 141–151

- ↑ Mickiewicz, op. cit., Book 12, verse 710

- ↑ [Wincentyna Zawadzka]: Kucharka litewska, Wilno: nakładem autorki, 1860, p. 62

- ↑ Mickiewicz, op. cit., księga VIII, wersy 794

- ↑ Jelena Tokarewa [Елена Токарева]: О происхождении сказания о «белгородском киселе», in: Древняя Русь в IX–XI веках: контексты летописных текстов, Зимовники: Зимовниковский краеведческий музей, 2016, p. 42

- ↑ Łukasz Gołębiowski: Domy i dwory, Warszawa: N. Glücksberg, 1830, p. 33

Bibliografia

- Agnieszka M. Bąbel: Garnek i księga – związki tekstu kulinarnego z tekstem literackim w literaturze polskiej XIX wieku, in: Teksty Drugie: Teoria literatury, krytyka, interpretacja, 6, Warszawa: Instytut Badań Literackich Polskiej Akademii Nauk, 2000, p. 163–181

- Maria Frankowska: Chołodziec, poezja i piernik, in: Pamiętnik Literacki: czasopismo kwartalne poświęcone historii i krytyce literatury polskiej, 87/1, Warszawa: Instytut Badań Literackich Polskiej Akademii Nauk, 1996, p. 141–151

- O. Kokosznicka: Sposób na jastrzębie i kanie, albo nowy środek wychowywania drobiu, Wilno: 1811

- Elena Slobodian: Słownik tematyczny języka poematu Adama Mickiewicza „Pan Tadeusz”, 2011

| ◀️ Previous | 📜 List of posts | Next ▶️ |

| ⏮️ First | 🎲 Random post | Latest ⏭️ |