Epic Cooking: The Decorous Rite of the Mushroom Hunt

Epic Cooking Food and Drink in “Pan Tadeusz”, the Polish National Epic |

Epic Cooking

Food and Drink in “Pan Tadeusz”,

the Polish National Epic

Have you been mushroom picking this year yet? If you’re Polish, then your answer is likely yes. In Poland, gathering wild mushrooms in a forest is something of a national pastime. As reported by a polling agency, more than three quarters of Poles have engaged in this activity at least once in their lifetime, and more than two fifths do it on a regular basis.[1] According to a classification scheme proposed over half a century ago by Mr. and Mrs. Wasson, who wrote a book on the role of mushrooms in the history and culture of Russia and the world,[2] the Poles, along with other Balto-Slavic nations and northern Italians, belong to mycophillic, or mushroom-loving, peoples. On the other end of the spectrum are mycophobic nations, which in Europe are mostly concentrated in the North Sea basin and whose risk acceptance in regards to mushroom picking only goes as far as picking up a plastic box of cultivated champignons in a supermarket.

Mycophobes may find the Polish passion for gathering, preserving and consuming wild mushrooms shockingly adventurous, foolhardy even. Isn’t it dangerous? Well, yes, mushroom poisoning does occur more often in Poland than it does in countries where mushroom picking simply isn’t a thing. But hardly as common as you might think. Within five years from 2009 to 2013, only eight people in western and central Poland died from mushroom poisoning (compared to 112 people who died from various alcohols, including 49 from methanol, and 95 who died from pharmaceutical drug overdose).[3]

Mushroom picking is a family pastime, so Polish and other mycophiles typically learn to tell edible mushrooms from inedible and poisonous ones at an early age. Until 1999, a lesson on mushroom species was part of Poland’s elementary school curriculum.[4] Many field guides – printed and online – are available too. But most Polish mushroomers learn to recognise fungal species from their parents or grandparents, and continue to gather the same few kinds of mushrooms (even though many more are edible too) which they learned to pick when they were children. Field guides do little to expand their preferences; they only seem to unify mushroom names used throughout the country.[5]

Painted by Ivan L. Gorokhov (1912)

So which mushrooms are most commonly picked in Poland?

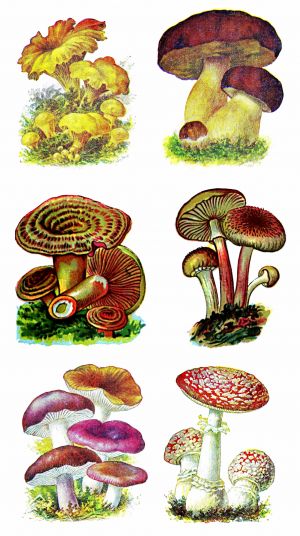

- The king bolete (Boletus edulis), also known as “penny bun”, “cep” or “porcino”, reigns supreme. In Polish, it’s known as “borowik szlachetny” (literally, “noble pine-forest mushroom”) or “prawdziwek” (“true mushroom”).

- The bay bolete (Imleria badia) is related, but less prized. Its second-best status is reflected in its Polish name, “podgrzybek”, which may be translated as “deputy mushroom” or “junior mushroom”. It’s popular enough in Poland that the Russians call it “polskiy grib”, or “Polish mushroom”.

- The golden chanterelle (Cantharellus cibarius), a bright-yellow trumpet-shaped mushroom with a slightly peppery flavour, called “kurka” (“little chick”) or “pieprznik” (“pepper mushroom”) in Polish, comes last on the podium. Mickiewicz referred to it as “lisica”, or “vixen”.

Further spots are taken by:

- various species of slippery jacks (genus Suillus), which the Poles refer to as “maślaki” (“butterballs”) because of their slimy caps;

- saffron milk cap (Lactarius deliciosus), a red-brownish mushroom which oozes a milky liquid when damaged; its Polish name is “rydz”, or “ginger-coloured mushroom”;

- parasol mushroom (Macrolepiota procera), or “kania” in Polish, whose broad flat cap may be fried in bread crumbs like a pork cutlet;

- honey mushroom (Armillaria mellea), small and sweetish, which grows in patches on tree stumps; its Polish name is “opieńka miodowa”, or “honey stumper”;

- some species of knight caps (genus Tricholoma), known in Polish as “gąski”, or “little geese”.

Mushroom season lasts from late summer to mid-autumn, but Polish people preserve most of the fungi they collect, so that they can enjoy them all year long. This they do mostly by drying and to a lesser extent by pickling in vinegar (mostly in the case of slippery jacks and other species which don’t lend themselves to drying) or, less traditionally, freezing. The Poles typically gather mushrooms for their own use, but they face competition from professional gatherers who, though less numerous (only 1% of all mushroomers), pick much larger quantities than recreational mushroom hunters do.[1]

This is the situation today. And what was it like in the past? “Mushrooming’s ancient and decorous rite” is described with great beauty in Pan Tadeusz, the Polish national epic written by Adam Mickiewicz🔊 in 1834. So let’s pay yet another visit to the fictional manor of Soplicowo🔊 and see what kinds of mushrooms the epic’s characters gathered and what use they later put them to.

“There Were Mushrooms Aplenty”

Painted by Franciszek Kostrzewski (ca. 1860)

A small grove, sparsely wooded, now came into sight; | ||||||

| — Adam Mickiewicz: Pan Tadeusz, or The Last Foray in Lithuania: A Tale of the Gentry during 1811-1812, translated by Marcel Weyland, Book III, verses 220–236 * The action takes place in early September (of 1811), at the height of mushroom season. The Polish adjective “majowych”, here mistranslated as “of May”, was actually used by Mickiewicz in the now largely forgotten sense of “vividly green”.

Original text:

|

The whole affair began when Lady Telimena, bored by the men’s heated argument about hare hunting at breakfast, declared that she was going out to gather saffron milk caps, then took Lord Chamberlain’s youngest daughter by the hand and left. Judge Soplica saw this as an opportunity to calm his guests down and announced a mushroom-picking competition:

“It is mushroom time, sirs, in the wood! | ||||

— A. Mickiewicz, op. cit., Book II, verses 846–850; own paraphrase of M. Weyland’s translation

Original text:

|

As we can already see at the very start, the most sought-after mushroom in Soplicowo was not the king bolete, but the saffron milk cap. But that’s not to mean that all other mushrooms were overlooked by the Judge’s guests. I remember the impression I had long ago, when I was reading Pan Tadeusz for the first time, that part of Book III was a veritable mushroom field guide in verse. So let’s see what species the poet mentioned in his epic:

There were mushrooms aplenty: the lads chanterelles gather, | ||||

— A. Mickiewicz, op. cit., Book III, verses 260–269; own paraphrase of M. Weyland’s translation

Original text:

|

Only three edible species? That’s not as many I thought. But a few hundred verses further, in a passage about the mushroom hunters coming home with their trophies, we can spot two more:

From the grove comes | ||||

— A. Mickiewicz, op. cit., Book III, verses 691–698; own paraphrase of M. Weyland’s translation

Original text:

|

All in all, there are five edible kinds of mushrooms (the fly agaric, here translated as “fly-bane”, is poisonous). The one we haven’t discussed yet is the brittlegill, which in fact refers to several species of the genus Russula. Mickiewicz calls them by the word “surojadki” (“eaten raw”), but the Polish term that is more common today is “gołąbki”, or “little pigeons”. They’re edible, but often ignored nowadays, as their taste is just okay and, having gills rather than pores on the underside of the cap, they can be confused with some toxic species.

Mushroom War

A small digression before we move on: what is this song which calls the king bolete “the colonel of mushrooms”? According to the poet’s explanatory note, it’s “a folk song well known in Lithuania about mushrooms marching to war under a king bolete’s command. This song describes the characteristics of edible mushrooms.”[8] Why did the author of a Polish epic draw inspiration from Lithuanian folklore? Because the Grand Duchy of Lithuania is where the story is set; in fact, the epic’s very first words are “Lithuania, my country”.[9] In the poet’s time, the Grand Duchy was a part of the Russian Empire that was inhabited by Polish-speaking nobility (which he belonged to himself), Belarusian or Lithuanian-speaking peasants and Yiddish-speaking Jews.

Anyway, Mickiewicz didn’t quote the song directly. But, as luck would have it, Mickiewiczologists were able to track down, more than a hundred years ago, its original Lithuanian-language lyrics. Here it goes, as noted down by Mr. and Mrs. Angrabaitis in what is now Lithuania’s Marijampolė County:

What did the little hare say when running through the wood? | ||||

— Lithuanian folk song as quoted in: Stanisław Windakiewicz: Prolegomena do „Pana Tadeusza”, Kraków: Gebethner i Wolff, 1918, p. 227–228, own translation

Original text:

|

As you can see, apart from the species mentioned in Pan Tadeusz, such as saffron milk caps, king boletes and stumpers (honey mushrooms), the song also mentioned other edible, if less prized, mushrooms: the red-capped scaber stalk (Leccinum aurantiacum) and the slippery jack. It could also be that the Lithuanian word “zuikužėlis” refers, in this case, not to a hare running around the forest, but to any of the mushrooms whose Lithuanian folk names derive from the word for “bunny”. These include the quite edible birch bolete (Leccinum scabrum) and the very inedible bitter bolete (Tylopilus felleus; this one is also known as “zajączek gorzki”, or “bitter bunny”, in Polish).[10] In any case, it’s quite possible that in Mickiewicz’s time the song had more verses and served as a real oral field guide to be sung while picking mushrooms.

While we’re digressing, let’s clarify one more thing: why did the Tribune gather fly agarics, the most recognizable of toxic toadstools? Was it just to show his contempt for any forest activity that didn’t involve hunting big game, the only pastime he thought becoming of a nobleman? Or did he intend to poison somebody? Or something. As we already know, the Tribune absolutely hated flies. And the fly agaric (Amanita muscaria), as both its English and Polish names imply (Polish “muchomor” literally means “fly-bane”), was used as insecticide for centuries. This is how:

| Dice a fresh fly agaric and cook it in boiling milk. Then pour the milk into cups for the flies [to drink] or smear it in the gaps where bedbugs are. | ||||

— Feliks Berdan: Muchomór, in: Encyklopedyja Powszechna, vol. XIX, Warszawa: S. Orgelbrand, 1865, p. 15, own translation

Original text:

|

Recipës

Painted by Tomasz Łosik (1883)

In the end, a bell called the mushroom hunters back to the manor for lunch. Even though originally the hunt had been Telimena’s idea, she must have been, as the Notary observed, looking for mushrooms in the trees, as she returned empty-handed from the wood. So did her two suitors, Thaddeus and the Count. We don’t know who won the Judge’s competition. Nor does the poem mention what happened with the mushrooms others had collected. We can only guess.

Anyone who has been to a mushroom hunt knows that after the fun part, which is the picking itself, you still have to sort, clean and dice the mushrooms, discard the wormy ones and decide which specimens are to be eaten right away and which are suitable for drying or pickling. Without a doubt the nobles delegated these thankless tasks to the servants, before settling down for lunch which the same servants had prepared.

Eventually, the mushrooms must have ended up on the nobles’ table. But in what form? The poet didn’t say; there is no mention of any mushroom-containing dishes anywhere in Pan Tadeusz. But that shouldn’t stop us from speculating about what mushroom dishes they could have enjoyed – based on cook books from the same period.

Let’s start with the saffron milk caps, which Mickiewicz considered to “have the best taste”. His friend, Karolina Nakwaska, who wrote a home-making book for women, gave a recipë that is perfect in its simplicity.

| Take carefully selected, worm-free saffron milk caps, remove the stems; if the caps are too big, then cut them in half. Arrange on a grill over a slow fire, place a small piece of butter in each cap, sprinkle with pepper and salt, and fry without flipping them over. You can use very good olive oil instead of butter. Add chopped parsley and onion. Serve after ten minutes. Saffron milk caps and [other] mushrooms fried simply in butter with onion, pepper and salt, are just perfect. | ||||

— Karolina Nakwaska: Dwór wiejski, vol. II, Lipsk: Księgarnia Michelsena, 1858, p. 199, own translation

Original text:

|

As for king boletes, Jan Szyttler advised to use them as a filling for little aromatic yeast pies. This is what he wrote in his cookbook, published a year before Pan Tadeusz:

| Cook some fresh king boletes in boiling water, then fry them with onion (as you normally would) and a small piece of dried bouillon; once fried, chop them up as finely as possible. Add four eggs, nutmeg and pepper. Roll out hard-kneaded yeast dough, then fill with the mushrooms as for kołdunki [i.e., pierogi, or filled dumplings], fry in fat until brown and serve hot. | ||||

— Jan Szyttler: Kucharz dobrze usposobiony, vol. I, Wilno: R. Daien, 1833, p. 52–53, own translation

Original text:

|

And what about the chanterelles, so praised in Lithuanian folk songs? Well, nothing! I haven’t found any recipës that would refer to this species of mushroom from before the 20th century. It looks like chanterelles weren’t as popular in Mickiewicz’s time as he made it seem. Or at least not in all circles.

Fungal Commoners

Hunter-gatherer cultures typically divide their labour along gender and age lines: men hunt, while women and children gather.[12] In farming societies, where foraging is no longer the chief source of food, but still helps expand the menu, this division is not only continued, but also expanded to include a class dimension: hunting, treated increasingly as a sport, is the domain of noblemen, while picking berries, nuts and herbs is left to peasants, especially women. In Pan Tadeusz, we can observe a pair of young peasants – a girl and a boy – collecting cowberries and hazelnuts.

Painted by Vasily T. Timofeyev (1879)

When a branch quivers, brushed, | ||||

— A. Mickiewicz, op. cit., Book IV, verses 81–88; own paraphrase of M. Weyland’s translation

Original text:

|

In this hierarchy of forest activities, mushroom picking was somewhere near the middle. Berry shrubs grow in vast patches, each identical to the next; a good mushroom, on the other hand, is hard to find and no two fungi are the same. So while regular gathering is a tedious, back-breaking chore, mushroom picking can be seen as a challenging or even competitive pastime. There’s a reason why it’s often called mushroom hunting. Fungi may lack claws or fangs, but the risk of poisoning adds a certain dose of excitement.

Just like recreational mushroom hunters today have to share the forest with professionals, so was mushroom picking in times of yore practised both by peasants – for whom it was a way to supplement their meagre diet – and by the nobility, who saw it as a more democratic alternative to big-game hunting. Note how, in Soplicowo, only the nobles engaged in the mushroom hunt, yet the party was still more inclusive (from the Chamberlain’s little daughter to the old Tribune) than at the bear hunt, which was a men-only affair.

Mushrooms are often considered one of the few foodstuffs used in Old Polish cuisine which crossed class boundaries and could be found on both peasant and lordly tables.

| Whereas nobility feasted on choice meats, rich cakes, and imported wines, the peasantry had to make do with groats, dumplings, cabbage, and coarse breads. Mushrooms were the great equalizer. They had a place of honor on the banquet tables of royalty, but were equally at home in the humble peasant cottage. |

| — Robert Strybel, Maria Strybel: Polish Heritage Cookery, New York: Hippocrene Books, 1993, p. 396 |

Except that this idealized picture isn’t quite true. There existed a mushroom hierarchy which paralleled the social one: the few choice varieties were reserved for the nobility, while commoners had to content themselves with more or less edible, but certainly less flavourful, species. Mind you, the forest and everything one could find there, belonged to the nobleman. The peasants were usually allowed to obtain certain goods in the lord’s forest, but they had to bring the better species of mushrooms as payment to his estate. One of these species was, without a doubt, the penny bun, which explains why it’s also called “king bolete” in English, “Herrenpilz” (“lord’s mushroom”) in German and “borowik szlachetny” (“noble mushroom”) in Polish. What other mushrooms did the nobles call dibs on?

| Of all mushrooms, the rich only knew king boletes, saffron milk caps, morels, champignons and truffles. | ||||

— Łukasz Gołębiowski: Domy i dwory, vol. IV, Warszawa: self-published, 1830, p. 47, own translation

Original text:

|

This short list is validated by Old Polish recipës, which don’t mention any other mushroom species. It turns out that the range of mushrooms appreciated by the high-born was quite limited. And even that only applied to the more intrepid ones who didn’t listen to the dieticians’ advice to stay away from all of these watery, dirty and certainly unhealthy (cold and moist in the highest degree) or even poisonous toadstools. Probably the oldest Polish recipë for mushrooms is the one given by Maciej Miechowita, the Renaissance-era court physician to King Sigismund I.

| Mushrooms, seasoned in the choicest manner, are best when tossed over the fence. No cure exists for their pernicious complexion. | ||||

— Maciej Miechowita, quoted in: Marcin z Urzędowa: Herbarz polski, to jest o przyrodzeniu ziół i drzew rozmaitych, i innych rzeczy do lekarstw należących, Kraków: Drukarnia Łazarzowa, 1595, p. [149], own translation

Original text:

|

The opinion which the Polish Enlightenment-era poet and publicist Stanisław Trembecki held of mushrooms wasn’t much better.

| Forest mushrooms arise from mould growing on rotting deadwood and pushing up from beneath the ground to structure itself on the surface! More than half of mushrooms constitute virulent poison, while other are less noxious and known as such. […] Every year, papers report entire houses extinct from mushroom consumption. Have mushrooms ever made anyone feel better? I forgive the pauper who, desperate for food, may risk any haphazard fare, but the well-to-do cannot be excused for devouring such filth out of perverted luxury. | ||||

— Stanisław Trembecki: Pokarmy, in: Pisma wszystkie, vol. 2, Warszawa: 1953, p. 206; quoted in: Grażyna Szelągowska: Grzyby w polskiej tradycji kulinarnej, in: Studia i Materiały Ośrodka Kultury Leśnej, 16, Ośrodek Kultury Leśnej w Gołuchowie, 2017, p. 214, own translation

Original text:

|

All this meant that the peasants were still left with quite a wide range of perfectly edible mushrooms which the nobles shunned in disgust.

| The yokel’s fare has always consisted of […] sundry mushrooms, such as brittlegills, […] tacked, fleecy and woolly milk caps, chanterelles, sooty heads, milk whites, stumpers, yellow knights, scaber stalks, butterballs; and in this abundance mistaking the poisonous ones for the good, he often pays with his health or even life. | ||||

— Ł. Gołębiowski, op. cit., s. 31–32, own translation

Original text:

|

As you can see, there was a time when chanterelles, so highly prized today, were treated with the same suspicion and contempt as all other peasant food. Some even thought them outright toxic.

| The chanterelle mushroom […] is readily used as food in certain places, […] yet it poses a dire hazard, often causing mighty stomach aches and diarrhoea. | ||||

— Krzysztof Kluk: Dykcyonarz roślinny, vol. I, Warszawa: Drukarnia Xięży Pijarów, 1805, p. 12–13, own translation

Original text:

|

It seems that it was only Mickiewicz, so fascinated by peasant culture, who had the nobles of Soplicowo forage for the mushroom plebs which, in real life, they wouldn’t even deign to look at.

Overlooked and Looked Down On

And then, there are the mushroom species which even the unfussy Soplicas didn’t pick. They’re all edible, but only so-so flavourwise. And yet, Mickiewicz devoted to them no less space in his epic than to those which ended up in the wicker baskets.

|

Other, more common, mushrooms did not win their favour | ||||

— A. Mickiewicz, op. cit., Book III, verses 270–279; own paraphrase of M. Weyland’s translation

Original text:

|

We’ve got here, again, various species of brittlegills; judging by the colours, they may be the milk-white brittlegill (Russula delica), yellow swamp brittlegill (Russula claroflava) and purple brittlegill (Russula atropurpurea). The foxy bolete (Leccinum scabrum), which the poet likened to the kulawka, an Old Polish round-bottomed party glass whose contents you have to quaff in a single gulp before you lay it back on the table, is known in Polish as “koźlarz sosnowy”, or “pine billy goat”. The horn of plenty (Craterellus cornucopioides), also known as “black trumpet” or “trumpet of death” (despite being edible), has a relatively unassuming Polish name: “lejkowiec”, which means “funnel mushroom”. The peppery milk cap (Lactarius piperatus) gets its appellation from its acrid taste and milk-white colour.

The beautifully descriptive similë, comparing toadstools to drinkware, brings us to the topic of Old Polish beverages. But let’s leave the subject of what was drunk at Soplicowo for another post. Meanwhile, let me end this post by quoting Mickiewicz’s admonition about how to deal with inedible mushrooms, which is as valid today as it was two centuries ago.

None those hares’ or wolves’ mushrooms to gather would deign, | ||||

— A. Mickiewicz, op. cit., Book III, verses 286–289

Original text:

|

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Marcin Herrmann: Uroczysty obrzęd grzybobrania, No. 143/2018, Warszawa: Centrum Badania Opinii Społecznej, October 2018

- ↑ Valentina Pavlovna Wasson, R. Gordon Wasson: Mushrooms, Russia and History, vol. 1, New York: Panthon Books, 1957, p. XVII

- ↑ As reported by six out of Poland’s ten toxicological centres. Anna Krakowiak et al.: Poisoning Deaths in Poland: Types and Frequencies Reported in Łódź, Kraków, Sosnowiec, Gdańsk, Wrocław and Poznań During 2009–2013, in: International Journal of Occupational Medicine and Environmental Health, 30 (6), 2017, p. 903

- ↑ Łukasz Łuczaj: Collecting and Learning to Identify Edible Fungi in Southeastern Poland: Age and Gender Differences, in: Ecology of Food and Nutrition, 50:4, Routledge, 2011, p. 321

- ↑ Ibid., p. 332

- ↑ Adam Mickiewicz: Pan Tadeusz, or The Last Foray in Lithuania: A Tale of the Gentry during 1811-1812, translated by Marcel Weyland, Book III, verses 691–694

- ↑ Ibid., Book III, verses 245–246

- ↑ Ibid., explanatory notes; own translation

- ↑ Ibid., Book I, verse 1

- ↑ Jūratė Lubienė: Žvėrių pavadinimai lietuvių kalbos mikonimų motyvacijos sistemoje, in: Res Humanitariae, Klaipėdos universitetas, 2014, p. 108

- ↑ A. Mickiewicz, op. cit., Book III, verses 698–699

- ↑ Recent archaeological and ethnographic research has called this assertion into question (note added on 7 July 2023). Source: Abigail Anderson, Sophia Chilczuk, Kaylie Nelson, Roxanne Ruther, Cara Wall-Scheffler: The Myth of Man the Hunter: Women’s contribution to the hunt across ethnographic contexts, in: PLoS ONE, 18 (6), Public Library of Science, 28 June 2023

- ↑ Ibid., Book IV, verses 83–84

- ↑ Ibid., Book III, verses 287–289

- ↑ Ibid., Book III, verses 287–289

Bibliography

- Andrzej Grzywacz: Tradycje zbiorów grzybów leśnych w Polsce, in: Studia i Materiały CEPL w Rogowie, 44/3, Centrum Edukacji Przyrodniczo-Leśnej w Rogowie, 2015, p. 189–199

- Internetinis grybų katalogas

- Marcin Kotowski: History of mushroom consumption and its impact on traditional view on mycobiota: an example from Poland, in: Microbial Biosystems, 4 (3), December 2009, p. 1–13

- Łukasz Łuczaj: Collecting and Learning to Identify Edible Fungi in Southeastern Poland: Age and Gender Differences, in: Ecology of Food and Nutrition, 50:4, Routledge, 2011, p. 319–336

- Grażyna Szelągowska: Grzyby w polskiej tradycji kulinarnej, in: Studia i Materiały Ośrodka Kultury Leśnej, 16, Ośrodek Kultury Leśnej w Gołuchowie, 2017, p. 213–225

| ◀️ Previous | 📜 List of posts | Next ▶️ |

| ⏮️ First | 🎲 Random post | Latest ⏭️ |