Epic Cooking: Supper in the Castle

Epic Cooking

Food and Drink in “Pan Tadeusz”,

the Polish National Epic

This is another post in a series about food in Pan Tadeusz, the Napoleonic-era Polish national epic by Adam Mickiewicz. While wandering around Europe after his exile from Russian-ruled Poland, Mickiewicz always kept in his travelling library an “old, worn cookbook”, which he would read from time to time “with great pleasure”, hoping to one day give a “truly Polish-Lithuanian banquet” according to “the ancient recipës”.[1] I will write about the title of this book in a different post. For now, it suffices to say that the poet never had the occasion to fulfill his dream of hosting a real-life Old Polish-Lithuanian feast and had to satisfy his culinary fantasies by conjuring up a perfect traditional banquet on the pages of Pan Tadeusz instead.

He placed his description of an old-fashioned “Polish dinner” in the books (chapters) XI and XII of the poem. In the earlier books, on the other hand, we can find depictions of the kind of meals the author could remember from his own youth in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania (a constituent nation of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, which covered not only the territory of the modern-day Republic of Lithuania, but also the much larger Belarus). To him, this was just the ordinary, daily fare of the “land of [his] childhood”. To us, though, it is what the cookery described in his treasured little book was to Mickiewicz – the forgotten world of Old Polish cuisine. And just like Mickiewicz would fantasize about recreating an Old Polish banquet, so would I like to share with you my own vision of a Pan Tadeusz-style supper. Someone someday may actually try to prepare a meal based on the menu I propose here; but for now let’s stick mostly to our imagination.

“They Supped Inside the Castle”

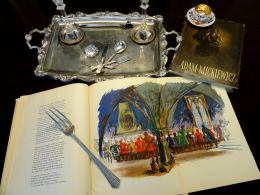

This and next frames come from Andrzej Wajda’s 1999 film adaptation of Pan Tadeusz.

I already wrote about the chronology of the meals described in Pan Tadeusz in my post about the epic’s breakfasts. As you may or may not remember, there are three afternoon or evening meals described in the first five books of the poem. These include a Friday supper in the Horeszko family’s ruined castle, a Saturday dinner at Judge Soplica’s manor house and a Sunday supper held in the castle again. We’ll try and piece together our menu from the poet’s descriptions of all three meals.

They supped inside the castle. Protase, no permission, | |||

| — Adam Mickiewicz: Pan Tadeusz, or The Last Foray in Lithuania: A Tale of the Gentry during 1811–1812, translated by Marcel Weyland, Book V, verses 305–308

Original text:

|

Why did Protase (Protazy), a former court usher and now Judge Soplica’s domestic servant, insist on having the supper in the murky ruins of an abandoned castle? Officially, because the castle, more spacious than the Judge’s house, could better accommodate the many guests who arrived for the conclusion of the court case between the Judge and the Count. But as the castle was what the whole litigation was actually about, it was Protase’s idea to prove that the Judge had gained ownership of the ruins through usucaption. In other words, if the Judge had his meals in the castle, then it surely meant that the real estate was legally his.

First Course

As you may know, the main meal of the day in Poland begins invariably with a bowl of soup. It was no different in Soplica’s house, except that, just before the soup, the men were served a small apéritif.

The guests entered in order and stood for the grace: | ||

| — Mickiewicz, op. cit., Book I, verses 300–307 (M. Weyland’s translation with modifications)

Original text:

|

The Poles have known for a long time that there’s nothing better than vodka to open a meal, but the West is only now beginning to discover clear vodka as the perfect apéritif. This is how two East Europeans living in the West, Nicholas Ermochkine and Peter Iglikowski, described it in their book:

| There is a long tradition confirming vodka’s vocation as an ideal aperitif. The custom at the banquets of Polish and Russian nobility was to offer male guests vodka before serving fine wines and quality ales for the remainder of the feast. […]

The function of a good aperitif is not just to whet the appetite, but to get people in the right mood for what follows. Champagne is a very good aperitif for this purpose, but vodka is even better. […] Two glasses of vodka can […] give a wholly unimagined dimension to the most tiring in-laws in record breaking time. If you want to get the evening off to a good start, then vodka as an aperitif is probably unbeatable. |

| — Nicholas Ermochkine, Peter Iglikowski: 40 Degrees East: An Anatomy of Vodka, New York: Nova Science Publishers, 2003, p. 24–25

|

Why was it only for men, though? Why didn’t the women get any vodka? After all, already in the 18th century, did the Rev. Jędrzej Kitowicz write of Polish noble ladies that they would “often get drunk on vodka”.[3] Or maybe that’s precisely the reason?

So this what the first course looked like on the first day. Was it any different on the second day?

The guests entered in order and stood for the grace: | ||

| — Mickiewicz, op. cit., Book III, verses 712–719 (M. Weyland’s translation with modifications)

Original text:

|

On the third day, the supper started according to the same scheme again, although with some slight modifications:

The guests entered in order and stood for the grace: | ||

| — Mickiewicz, op. cit., Book V, verses 309–318 (M. Weyland’s translation with modifications)

Original text:

|

This ritual repetitiveness of Soplica’s meals was adjusted only to the season and to the Catholic calendar of feasts and fasts. In this case, it’s Lithuanian cold borscht, a summertime soup that is still as popular on hot days in both Lithuania and Poland as gazpacho is in Spain.

There is a linguistic problem here, though. Mickiewicz has used two different terms, “chłodnik”🔊 and “chołodziec”🔊. Both words derive from the adjective “chłodny”, or “cold”, but while Mickiewiczologists have no doubt that “chłodnik” refers to a cold soup, there is some disagreement as to what kind of dish chołodziec was.[4] Is it a regional name for the same soup or does it refer to an aspic dish? After all, the similar Russian word “холодец” (kholodets) refers to a meat-based jelly. It could be possible that this term had filtered into the eastern dialects of Polish. Besides, veal feet in aspic would have paired perfectly with the vodka.

On the other hand, the vodka was served to men only, but the chołodziec was consumed by all. What’s more, there’s no evidence that, in the 19th century, the word was used for aspic anywhere outside certain regions of Russia proper; it’s not attested in either Polish or Belarusian of the time (of course, aspic dishes themselves had been known since the Middle Ages, albeit under other names). Anyway, the oldest translations of Pan Tadeusz into both Russian and Belarusian treat both “chłodnik” and “chołodziec” as referring to a soup. It looks like both Mickiewicz himself and his contemporary translators had no doubts that these two words were synonymous.

There’s another interesting difference, though. On the third day, the cold borscht was “whitened”, or clouded with sour cream, but on the first and second days, it wasn’t. Why? One possible explanation would be that the first two days were Friday and Saturday, that is, lean days. In Polish tradition, dairy products, as well as meat, were proscribed on lean days. It was only on Sunday that the same cold borscht was served again, but this time, enhanced with the luxurious additive. Except that if the Soplicas fasted on Saturday, then they must have done it only in the afternoon, because for breakfast they’d had not only cream, but even smoked goose breasts, beef tongues, ham and steaks! This may be explained away only by the poet’s inconsistency.

So how do you prepare this whitened Lithuanian cold borscht? Here’s a recipë from The Lithuanian Cook, a Polish-language cookbook by Wincentyna Zawadzka. The first edition was published two decades after Mickiewicz had penned Pan Tadeusz, but I suppose the recipë would have been quite similar in his times. Heck, even today Lithuanian cold borscht is still made in pretty much the same fashion.

| Grind a large handful of chopped fresh dill together with salt. Boil some chopped sorrel, chards or red beetroots and leave to cool down. Add some meat broth, half a gallon of sour cream, mix it all together and adjust the thickness and sourness by adding more of either the broth or the cream, so that the soup is white and cloudy. Just before serving, add a few chunks of ice, a few quartered hard-boiled eggs, a few finely chopped cucumbers, threescore crayfish tails or some large cooked fish, or if you don’t have any, some roasted veal cut into thin stripes. If you have cauliflower or asparagus, then you can add some that was boiled separately in water, cooled down and broken into chunks. | ||

| — [Wincentyna Zawadzka]: Kucharka litewska, Wilno: nakładem autorki, 1860, p. 29, own translation

Original text:

|

Second Course

Now that we know what they had for soup, let’s find out what was served as the second course.

Next came crayfish and chicken, asparagus stalks, | ||

| — Mickiewicz, op. cit., Book V, verses 319–320 (M. Weyland’s translation with modifications)

Original text:

|

And here we’ve got another puzzle which Mickiewiczologists have been trying to figure out for decades. Crayfish was easily available in late summer, chicken possibly too, but asparagus? The season for asparagus is in May, right? So how could it find itself on the table next to the late-summer crayfish? Was it only for the rhyme? Or is this yet another of the poet’s mistakes who seems to have juggled the seasons quite liberally in his work?

| In this paradise, springtime flowers are in bloom alongside ripening autumn fruits. At the same time, violets and Michaelmas daisies grace some perfect season, in which poppies charm the eye with a “multi-hued show”, in which the pumpkin ripens, farmers harvest grains and mow grass, and the feast of Our Lady of the Herbs falls on Palm Sunday. | ||

| — Julian Przyboś: Czytając Mickiewicza, Warszawa: Państwowy Instytut Wydawniczy, 1965; cyt. w: Halina Szymanderska: Sekret kucharski, czyli co jadano w Soplicowie, Warszawa: Prószyński i S-ka, 1999, p. 6; cyt. w: Agnieszka M. Bąbel: Garnek i księga – związki tekstu kulinarnego z tekstem literackim w literaturze polskiej XIX wieku, in: Teksty Drugie: Teoria literatury, krytyka, interpretacja, 6, Warszawa: Instytut Badań Literackich Polskiej Akademii Nauk, 2000, p. 164, own translation

Original text:

|

“Disturbed, shaken, uncertain,” we begin to doubt the realism of the epic’s setting. But no, “such master errs not!”[5] It’s perfectly possible to defend the presence of asparagus in early September. After all, the poet didn’t specify that it was fresh asparagus. And the art of pickling the vegetable had been known in Poland for ages. Here’s a recipë for vinegar-cured asparagus from a 17th-century herbal written by a Polish Renaissance botanist, Prof. Simon Syrenius (Szymon Syreński):

| Take fresh [asparagus] sprouts, spread them in bowls, sprinkle with salt and leave in the shade for two days, then douse them with the liquid they emit. And should they not exude any moisture, then wash them in brine and press down with a weight, then put them in a glazed pot, cover well with two parts wine vinegar and one part brine, adding a generous amount of fennel. This way, all year long you may have a fine delicacy on your table. | ||

| — Simon Syrennius: Zielnik, Kraków: 1613, p. 1128–1129, own translation

Original text:

|

Very well, but how do you combine these pickles with chicken and crayfish into one dish? Let’s consult The Lithuanian Cook once again. We can find there a recipë for “chicken with mayonnaise”, elegantly garnished with, that’s right, asparagus and crayfish (and cauliflower to boot).

| Put whole young, well-fattened chickens into vegetable broth, along with a spoonful of butter, a chunk of beef or pork and cook under cover. Once they are soft, retrieve them, let cool, cut into pieces and remove the skin. Arrange them on a platter, dress with mayonnaise and garnish with cooked asparagus, cauliflower, crayfish tails (which should have been first bathed in vinegar with olive oil) and serve with a cold sauce of hard-boiled yolks ground together with sugar, vinegar and olive oil. | ||

| — Zawadzka, op. cit., p. 195, own translation

Original text:

|

Naturally, if you use pickled asparagus, then don’t add too much vinegar into this dish. This quite sour course would have been paired with sweet Malaga wine. And if you’ve got too much asparagus and crayfish on your hands, then you may also add them to your cold borscht, as you could see in the recipë for the first-course dish.

Third Course

After the second course, it’s time for the third. What does the poet tell us about it?

The third course had been served. And then Lord Chamberlain, | ||

| — Mickiewicz, op. cit., Book I, verses 332–336

Original text:

|

So, not much. All we know is that gherkins or cucumbers were served on the side. But what about the meat? We’re going to have to complete the picture with our own imagination. After a rather light poultry course, I suppose it’s time for something more substantial. And as August and September are mutton season, then why not have some ram meat? Let’s take the first recipë for mutton that we can find in The Lithuanian Cook:

| Marinate a large mutton roast for a few days in vinegar that has been boiled with spices; remove, press out the liquid, lard with sticks of pork fatback and stew on low heat in a saucepan, along with chopped onion, lard, a few juniper berries, various soup greens and a glass of bouillon or wine. Serve with strong bouillon-based gravy mixed with strained roast drippings and seasoned with lemon, capers or olives. | ||

| — Zawadzka, op. cit., p. 105–106, own translation

Original text:

|

And, from the same book, a recipë for “stewed cucumbers to be served with mutton”:

| Take a few or more fresh cucumbers, peel, cut lengthwise, salt and leave for half an hour. Melt a spoonful of butter, sauté a finely chopped onion in it, mix in the cucumbers and stew them until soft. Finally, sprinkle the cucumbers with flour, stew some more, douse with some good bouillon, bring to boil and, when serving, use them as a garnish for the meat. | ||

| — Zawadzka, op. cit., p. 62, own translation

Original text:

|

Early September may be somewhat late for fresh cucumbers, but we do know that Sophie (Zosia), Thaddeus’s young love interest, picked them with her own hand in her little garden.

Near the fence long mounds, convex, with greenery filled, | ||

| — Mickiewicz, op. cit., Book II, verses 430–435 * The Polish adjective “majowej”, here mistranslated as “May”, was actually used by Mickiewicz in the now largely forgotten sense of “vividly green”. Original text:

|

But even if cukes were no longer in season, Zawadzka assures us that “brine-pickled cucumbers may be stewed in the same way”.[6] And so, we’ve got another course that is both greasy and sour: fat mutton marinated in vinegar, pickled gherkins and all of it stewed in lard or butter. This will be accompanied by Hungarian Tokay wine.

Fourth Course

[…] with the fourth course, |

| — Mickiewicz, op. cit., Book I, verses 537–538

|

Whoa, hold on! A fourth course? How many courses were there, then? Well, a minimum of four. A two-course dinner is the norm in what we consider traditional Polish cuisine today, but in the 19th century a dinner in a well-to-do home rarely consisted of fewer than four courses. Not counting the dessert.

Alas, all that we know about the fourth course served at Judge Soplica’s is that it was there. The poet doesn’t tell us anything about what exactly was being eaten. Instead, we have a description of a drunken brawl which broke out during the second supper in the castle. Glasses, bottles, knives, tables, even organ pipes were all used as weapons. When the dust settled, the diners had gone, leaving behind a battlefield strewn with remnants of the feast. Perhaps from these food scraps we can read what had been served towards the end of the meal?

No loss there of life human, but benches and chairs | ||

| — Mickiewicz, op. cit., Book V, verses 793–810

Original text:

|

It looks like poultry, including turkeys, returned to the table after the third course. Even though turkeys come originally from America, they became quite popular in Poland not long after Columbus’s journeys. On European tables, they quickly replaced other large birds, like peafowl and swans, which from then on were raised mostly for decorative purposes. By the 19th century, the turkey had already been considered a time-honoured Old Polish delicacy.

At Judge Soplica’s farm, turkeys, chickens and other poultry, including ducks, geese and pigeons, were all raised by an eminent expert, the housekeeper,…

[…] a lady of fame, | ||

| — Mickiewicz, op. cit., Book III, verses 28–36

Original text:

|

As with many minor characters in Pan Tadeusz, her name is telling; “Kokosznicka z domu Jendykowiczówna” could be translated as “Mrs. Hen née Turkey”. Anyway, she had a little, well-meaning, even if sometimes overzealous, helper in Sophie, who fed the poultry with expensive pearl barley.

Sophie, dressed for the morning, and with her head bare, | ||

| — Mickiewicz, op. cit., Book V, verses 55–84 (M. Weyland’s translation with modifications)

Original text:

|

So how would we cook such a turkey fattened on lordly pearl barley? The chicken served for the second course was boiled, so this time let’s have a roast.

| Pluck and dress young turkeys and leave in a cold place for a few days to let them age. Lard them and salt a little, wrap in paper and roast on a spit, while dousing them with melted butter. When almost done, remove the paper and drench with béchamel sauce; once it becomes golden in colour, remove [the turkey] carefully from the spit, so that [the sauce] doesn’t fall off. To make the béchamel, melt a piece of butter, add a spoonful of flour, mix well, add a pint of milk or cream and three yolks, and bring to boil while stirring […] | ||

| — Zawadzka, op. cit., p. 123, own translation

Original text:

|

And to wash it down – Champagne, which (somewhat surprisingly) is mentioned about as often in Pan Tadeusz as Tokay, the stereotypically favourite wine of Polish nobility.

Dessert

Of desserts that were served at Judge Soplica’s we know nothing. Most of the meals described in the poem were interrupted in some way before the waiters even had the chance to bring in the sweets. The only sweet treat mentioned in Pan Tadeusz is kisiel and only in a proverb at that.

And why, out of the woodwork, did this Count appear? | ||

| — Mickiewicz, op. cit., Book VI, verses 169–171 (M. Weyland’s translation with modifications)

Original text:

|

If you’ve never heard of kisiel🔊 or of this saying, don’t worry. Mickiewicz apparently thought that even Polish people living outside Lithuania might be unfamiliar with either of these, so he added the following explanatory footnote:

| Kisiel, a Lithuanian dish, is a kind of jelly made from an oatmeal solution; water is poured on oatmeal until all the starchy parts are washed away; hence the proverb. | ||

| — Mickiewicz, op. cit., explanatory notes, own translation

Original text:

|

In other words, “tenth water on kisiel” refers to a very distant relation. The saying is still used in modern Polish, just as kisiel is still a popular dessert. It’s also a very ancient one, although originally it wasn’t sweet at all. The very word “kisiel” comes from the verb “kisić”, “to make sour”. The ancient Slavic kisiel was a mouth-puckering white jelly made from a fermented mixture of water and oat or rye meal. A similar concoction is still used in Poland as the basis for żurek, or white borscht, one of the most popular Polish soups. It was made just as Mickiewicz described it: by pouring water on oatmeal and leaving the starchy solution to ferment until it becomes sour and gelatinous enough to be cut with a knife. For ancient Slavs, this was one of the principal staples. A mythical land of plenty is described in Russian fairy tales as rivers of milk between banks of kisiel. The Tale of Bygone Years, a 12th-century chronicle of Kyivan Ruthenia (or Kievan Rus’), even tells a story of how kisiel saved the city of Belgorod from an invasion by the nomadic Pechenegs. During the siege, a respected old Belgorodian man advised his compatriots to dig a deep well, fill it with water and oat starch, and wait until it went sour. Then they invited Pecheneg envoys into the city to show them the well, let them try the kisiel and convince them that they were getting their food straight from the ground, so any further siege made no sense and it would be best for the Pechenegs to go back to the steppe and leave Belgorod alone.[8]

Łukasz Gołębiowski, one of the first Polish ethnographers, said that “the Poles had been always partial to tart dishes, which are somewhat peculiar to their homeland and vital to their health”,[9] but it seems to be true for other Slavic peoples as well. Even so, there must have always been those who tried to balance the sourness with something sweet, be it honey or fruit juices. And so did kisiel eventually evolve into a sweet, fruit-flavoured dish. Finally, in the 19th century, oatmeal gave way to potato starch and thus the kisiel we know today was born. The recipë for apple-flavoured kisiel you can read below, taken from The Lithuanian Cook, is already a relatively modern one; it contains potato starch and sugar, and no fermentation is necessary.

| Peel and cut the apples, boil them in water until soft and press through a sieve. Season with cinnamon and sugar, add as much water as to get six glasses of the mixture and combine some of it with a glass of potato starch. Bring the rest to boil, add the potato-starch mixture and stir for a few minutes while cooking. Wash the mould with water, sprinkle with sugar, fill with the kisiel and leave in a cold place. | ||

| — Zawadzka, op. cit., p. 422, own translation

Original text:

|

And finally, just to make the dessert a tad more diverse and make use of some other autumn fruits, let’s add one more recipë from the same source, this one for pear compote. In modern Polish, “kompot” refers to a popular watery drink made from fruits boiled with sugar. In the 19th century, though, the meaning was closer to the French original, that is, a thick and very sweet fruit syrup. In fact, you could simply buy a tin of pears in syrup, pour them into bowls, add some spices and the effect would be almost the same.

| Take a dozen or more small pears, peel, cut in halves with a grooved knife, remove the cores and throw the pears into boiling water seasoned with sugar, pieces of cinnamon and cloves. Once the pears are soft, scoop them out, strain and reduce the liquid, add half a pound of sugar […] and a sliced lemon without seeds, boil again until thick and pour on the pears arranged in a bowl. If the pears are large, then cut them into chunks. | ||

| — Zawadzka, op. cit., p. 419–420, own translation

Original text:

|

Full Menu

References

- ↑ Excerpts quoted from a letter by Antoni Edward Odyniec, Mickiewicz’s travel companion, dated 28 April 1830, quoted in: Izabela Jarosińska: Kuchnia polska i romantyczna, Kraków: 1994, p. 206; quoted in: Agnieszka M. Bąbel: Garnek i księga – związki tekstu kulinarnego z tekstem literackim w literaturze polskiej XIX wieku, in: Teksty Drugie: Teoria literatury, krytyka, interpretacja, 6, Warszawa: Instytut Badań Literackich Polskiej Akademii Nauk, 2000, p. 165

- ↑ Adam Mickiewicz: Pan Tadeusz, or The Last Foray in Lithuania: A Tale of the Gentry during 1811–1812, translated by Marcel Weyland, Book I, verses 262–263

- ↑ Jędrzej Kitowicz: O trunkach, in: Opis obyczajów i zwyczajów za panowania Augusta III, Poznań: 1840, p. 211–212

- ↑ Maria Frankowska: Chołodziec, poezja i piernik, in: Pamiętnik Literacki: czasopismo kwartalne poświęcone historii i krytyce literatury polskiej, 87/1, Warszawa: Instytut Badań Literackich Polskiej Akademii Nauk, 1996, p. 141–151

- ↑ Mickiewicz, op. cit., Book 12, verse 710

- ↑ [Wincentyna Zawadzka]: Kucharka litewska, Wilno: nakładem autorki, 1860, p. 62

- ↑ Mickiewicz, op. cit., Book V, verse 727

- ↑ Елена Токарева: О происхождении сказания о «белгородском киселе», in: Древняя Русь в IX–XI веках: контексты летописных текстов, Зимовники: Зимовниковский краеведческий музей, 2016, p. 42

- ↑ Łukasz Gołębiowski: Domy i dwory, Warszawa: N. Glücksberg, 1830, p. 33

Bibliography

- Agnieszka M. Bąbel: Garnek i księga – związki tekstu kulinarnego z tekstem literackim w literaturze polskiej XIX wieku, in: Teksty Drugie: Teoria literatury, krytyka, interpretacja, 6, Warszawa: Instytut Badań Literackich Polskiej Akademii Nauk, 2000, p. 163–181

- Maria Frankowska: Chołodziec, poezja i piernik, in: Pamiętnik Literacki: czasopismo kwartalne poświęcone historii i krytyce literatury polskiej, 87/1, Warszawa: Instytut Badań Literackich Polskiej Akademii Nauk, 1996, p. 141–151

- O. Kokosznicka: One Sure Defence Against Goshawks and Kites, Or, A New Method Simple For The Raising of Poultry, Vilnius: 1811

- Elena Slobodian: Słownik tematyczny języka poematu Adama Mickiewicza „Pan Tadeusz”, 2011

| ◀️ Previous | 📜 List of posts | Next ▶️ |

| ⏮️ First | 🎲 Random post | Latest ⏭️ |