Epic Cooking: The Perfect Cook

Epic Cooking

Food and Drink in “Pan Tadeusz”,

the Polish National Epic

Once again, we’re coming back to Pan Tadeusz, the 19th-century Polish national epic by Adam Mickiewicz. There’s still plenty of food and drink in this epic poem to discuss. In this series’ previous posts we focused on the first ten books, or chapters; now it’s time for the remaining two. There’s a considerable difference between books XI and XII, and the earlier parts of the epic. First, there’s a leap in time: books I to X are set within five days of the late summer of 1811; then we skip over all of autumn and winter, right into the spring of 1812 – a spring “profuse with events, pregnant with hope”,[1] as the poet reminisces. We can also observe a change in culinary terms: in the earlier books, the characters were having their everyday breakfasts, dinners and suppers that weren’t any different from those eaten by actual Polish nobility in the early 19th century – which was also what the poet could have remembered from his own youth. But in Book XI, the village of Soplicowo🔊 is visited by the Polish soldiers serving in Napoleon’s Grande Armée, on their way to Moscow. A great feast is given in their honour. Gen. Jan Henryk Dąbrowski🔊, the guy the Polish national anthem is about) makes a request “that for the fete, he would like Polish cooking.”[2] Therefore, the magnificent banquet consists of Old Polish dishes, whose names sounded foreign even in the ears of Mickiewicz himself – let alone in those of modern Poles! We’re going to have a closer look at the feast itself, as described in the epic’s final book, in the next post. But first, let’s take a peek inside the Soplicowo manor’s kitchen, managed by Tribune Hreczecha.

“Hreczecha is My Name”

From an illustration by Michał Elwiro Andriolli (1881)

Let’s start by saying a few words about the Tribune himself, one of the more colourful characters in Pan Tadeusz. We don’t know his first name, but we do know that his surname was Hreczecha🔊. “Tribune” (Polish “wojski”, Latin “tribunus”) was a medieval title, originally used by officials who took care of knights’ wives and children while their husbands were away at war; in Hreczecha’s case, it was an unofficial honorific awarded by the local gentry out of respect for the old man. He was a middle-income nobleman, also known as a grykosiej, or “buckwheat-sower” (in fact, Hreczecha’s own surname comes from “hrechka”, the Belarusian word for buckwheat). Even though he had his own estate (he could afford to give his younger daughter, Tekla, a village in dowry), he preferred to live, along with Tekla, in the household of Judge Soplica, his more affluent friend, distant relative and might-have-been son-in-law (the Judge, in his youth, had been engaged to Marta, the Tribune’s elder daughter, but she died before the wedding could take place and he would never marry anyone else). In Soplicowo, the Tribune had the role of a kind of seneschal, managing the Judge’s domestic servants.

Earlier, the Tribune “with gentry had spent his life, eating, at assemblies, […] or at council meeting[s]”,[4] where he mastered the ancient Lithuanian art of knife throwing. But it was in the realm of hunting that the Tribune was considered a real expert. He had learned this skill as a young man serving at the court of Tadeusz Rejtan, a Polish national hero. The Tribune remembered him not as a model patriot, though, but as a master hunter. As for his choice of game, he would always go for one of two extremes: on the one hand he believed that only large animals with horns, claws or fangs were worthy of being hunted by a nobleman. In his view, chasing hares was a good sport for youngsters and servants. “Hreczecha is my name – was his saying – since King Lech, it’s no habit of a single Hreczecha to follow a rabbit.”[5] On the other hand, he was spending a lot of time hunting flies. He would always carry a flyswatter around and, when mushroom picking (a popular Polish pastime, then and now), he would forage for fly agarics, a species of fungus used for killing the pesky insects.

The Tribune was also a big talker. He could talk for hours on end about astrology, flies’ mating habits, local assemblies and, most of all, about hunting. The poem is interspersed with the Tribune’s chatter – often in episodes, as he keeps getting interrupted. He manages to finish only some of his stories by the end of the epic, but there’s also one whose ending the poet had to recount in a footnote. Silence made the Tribune feel tired, so whenever he couldn’t find anyone to converse with, he would run off to the noisy kitchen.

“The Tribune, that the firewood more easily should

Catch alight, bids that butter be poured on the wood

(In a well-to-do house such waste can be forgiven).”[6]

Etching by Daniel Chodowiecki (1764)

The Tribune, […] | |||

| — Adam Mickiewicz: Pan Tadeusz, or The Last Foray in Lithuania: A Tale of the Gentry during 1811-1812, translated by Marcel Weyland, Book VI, verses 64–69

Original text:

|

Maybe this is how he got his culinary expertise?

In his formative years, which he most likely spent at some Jesuit school, the Tribune must have been made to read classic epics, such as Homer’s Iliad or Vergil Maro’s Aeneid. He would later refer to the latter as “my friend Maro”,[7] even though he probably knew the Aeneid ’s plot from scholars’ commentaries rather than from the epic itself. Mickiewicz too, no doubt, had to read the same classics, in their 18th-century Polish translations, as a schoolboy. And while he didn’t think very highly of these translations’ poetic value, they must have left a deep impression on his memory. Take, for example, this excerpt from Book XI of Pan Tadeusz:

All now slumber: the soldiers, the leaders, the host; | ||

| — A. Mickiewicz, op. cit., Book XI, verses 99–102

Original text:

|

And now compare it with the initial verses of the second book of the Iliad:

All now slumbered: the Gods and the mortal host; | |||

| — own paraphrase based on: Homer: Iliads, English translation by Thomas Hobbes; in: Thomas Hobbes: The English Works, edited by Sir William Molesworth, vol. X, London: Longman, Brown, Green, and Longman, 1839–1845

Original text:

|

The rhyme is the same, but here we’ve got the god of all gods making plans for the Troyan War, while there we have a simple nobleman making plans for a dinner. Mind you, it’s not the only such parallel; in fact, much of Pan Tadeusz is a parody of an 18th-century Polish translation of the Iliad. Interestingly, Mickiewicz is most likely to paraphrase Homer when he’s writing about the Tribune. This is no coincidence; for every time the Tribune gets busy in the kitchen, we’re in for some epic cooking!

“A Dear Souvenir of Righteous Customs”

“What the Tribune’s perusal makes known, without fail the skilled cooks at once carry all out to the letter.”[8]

Sketch by Jacek Malczewski (1871)

Where did the Tribune get his ideas for all the dishes to be served at the last Old Polish feast from? Well, he didn’t rely on his own memory, nor on any home recipës, but he carefully reached for an old printed cookbook.

[The Tribune] held a fly-swat, and with it drove back | ||

| — A. Mickiewicz, op. cit., Book XI, verses 114–122

Original text:

|

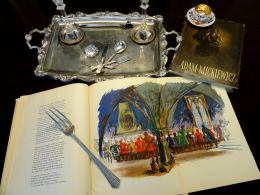

In a footnote, Mickiewicz adds that it’s “now a very rare book, published over a hundred years ago by Stanisław Czerniecki🔊.”[9] And this is where it gets tricky. A Polish cookbook entitled Kucharz doskonały (The Excellent Cook or The Perfect Cook, depending on how you translate it) did exist, but it was first published only in 1783, which was less than half a century rather than “over a hundred years” before Pan Tadeusz. What’s more, it wasn’t written by Stanisław Czerniecki. It was actually La cuisinière bourgeoise by Menon, translated into Polish and published by Wojciech Wielądko🔊, a man who otherwise had little to do with catering business. All the Tribune would have found there were French culinary novelties rather than time-honoured Old Polish recipës.

A copy of Compendium ferculorum by Stanisław Czerniecki opened on the author’s dedication to Princess Helena Tekla Lubomirska

So what was it about Czerniecki? Well, he was indeed an experienced chef, responsible for setting up aristocratic banquets for thousands of guests and also the author of the first[10] cookbook printed in the Polish language. Only that this book – or, rather, a booklet, as it was small enough to fit into a pocket on one’s chest, which was where the Tribune held it – had the bilingual, Latin-Polish title: Compendium Ferculorum albo Zebranie potraw (both parts meaning A Collection of Dishes). And it was – as we shall see in the next post – precisely from this book that the Tribune got the recipës for all the dishes he would serve at the great banquet in Book XII.

Besides, it wasn’t only the recipës that Mickiewicz took from the Compendium. The mention of the dinner given by the “Count of Tęczyn” to Pope Urban VIII in Rome was also inspired by the same cookbook, and specifically, by the dedication its author addressed to his employer, Princess Helena Tekla Lubomirska. Princess Lubomirska, the wife of Prince Aleksander Michał Lubomirski, took active part in Polish political life; she was also a great patroness of arts. Wacław Potocki and Jan Andrzej Morsztyn, whom I have quoted in some of my previous posts, dedicated their poems to her, while Czerniecki did the same with his cookbook. In the dedication, he recalled the time when, in 1633, her father, Prince Jerzy Ossoliński, Grand Chancellor of the Crown (roughly equivalent to a prime minister), was sent by the king of Poland as an envoy to the Holy See. At the time, the Polish Commonwealth was at the peak of its might and glory, a fact Ossoliński was not going to let anyone fail to notice. His retinue included the famed winged hussars, crimson-and-gold-upholstered carriages, ten camels carrying opulent presents for the pope, while the prince’s mount was dressed in diamonds, pearls and rubies, and deliberately shod with loose golden horseshoes – so that the horse could lose them along the way for everyone to see. The banquet which Ossoliński gave to the pope was without a doubt no less osstentatious. This is how Czerniecki described it:

| Still freshly remembered in German and Italian lands is the peerless and greatly impressive legacy of your dear Father, His Grace, Prince Jerzy Ossoliński of blessed memory, Grand Chancellor of the Crown, to the Holy See and to the Vicar of Christ, Urban VIII, which was greatly admired by all of the West, as was the splendor of the court and table of His Grace, so that the princes and lords of Rome, led by their curiosity, were coming to wonder at the abundance of the dishes and, having seen more than they had heard of, amazed they left. As they could not get enough of the view of this munificence, which left none unsatisfied, one of the Roman princes proclaimed, “Rome is fortunate to receive such an envoy today, who has made the Papal States brighter by his presence.” | ||

| — Stanisław Czerniecki: Compendium ferculorum albo Zebranie potraw, Kraków: w drukarni Jerzego i Mikołaja Schedlów, 1682, p. [IV–VI], own translation

Original text:

|

Etching by Stefano della Bella (1633)

Of course, Mickiewicz reversed the sequence of events in his poem; if Czerniecki described the Roman banquet as a historical fact in his cookbook, then the same banquet couldn’t have been prepared according to the instructions from the same cookbook.

Anyway, it looks like the poet confused two different cookery books (which are, as it happens, the only two surviving Polish-language cookbooks printed before the end of the 18th century) – Czerniecki’s Compendium Ferculorum, published in 1682, and Wielądko’s The Perfect Cook, published a hundred years later. How did this come to pass? Was it a mistake or poetic license? Maybe The Perfect Cook simply ringed better in the poet’s ear than the bland A Collection of Dishes, so Mickiewicz switched the titles on purpose? But if so, then he could have at least explained this manipulation in a footnote. If he hadn’t, then perhaps it was because he was genuinely mistaken himself. This conjecture is confirmed by a letter written by Edward Odyniec, who travelled together with Adam Mickiewicz in Italy, where he mentions a worn copy of a piece of culinary literature that the poet always carried in his luggage.

| Adam suggested to give a purely Polish-Lithuanian feast, according to ancient recipës from “The Perfect Cook”, a tattered old book which he carries around like some treasure in his travelling library and often reads with great pleasure. Obviously, this idea fell through […] | ||

| — Edward Odyniec, letter of 28 April 1830, quoted in: Izabela Jarosińska: Kuchnia polska i romantyczna, Kraków: Wydawnictwo Literackie, 1994, p. 62, own translation

Original text:

|

Title page of Kucharz doskonały (The Perfect Cook) by Wojciech Wielądko

Distinguished Mickiewiczologist, Prof. Stanisław Pigoń, once suggested a rather convincing solution to this puzzle: the book that Mickiewicz loved to read when pining for Polish cuisine and dreaming of having an actual Old Polish banquet was indeed Compendium ferculorum, but it was old and tattered, and missing its title page. So Mickiewicz knew very well the contents of the work and the dedication, as well as the author’s name, but he was ignorant of the book’s title. On the other hand, he probably never read The Perfect Cook, but he might have heard about it; the title could have stuck in his head and he may have later associated it with the mysterious treasure-trove of Old Polish recipës that had somehow found its way into his hands.

And how did it find its way into his hands? Well, it seems that Mickiewicz intended to tell us that through the Tribune’s mouth. The Tribune thought his cookbook so precious that he considered it a worthy gift for Gen. Dąbrowski. While presenting the book to the general, he was also going to recount the itinerary the book had travelled until it wandered into Soplicowo.

I doubt if such occasion will come once again | ||

| — A. Mickiewicz, op. cit., Book XII, verses 217–224

Original text:

|

Aaand this is where the Tribune got interrupted again. And there would be no later occasion to pick up the thread. Now that our appetite for an interesting story has been whetted, the dish is being snatched away from our mouths! But don’t despair, not all is lost; if something’s missing in the canonical version, then maybe we can find it in the deleted scenes? That’s right! There’s an original manuscript version of Pan Tadeusz with a passage that never made it into print. It says that the Tribune’s cookbook originally belonged to a Greater Poland nobleman called Captain Poniński who used this book to give opulent feasts. Before he died, he had given it to his neighbour, Lord Skórzewski🔊, who lived in the village of Kopaszewo🔊. His widow, Lady Skórzewska, in turn, offered it to Bartek Dobrzyński, a Lithuanian who often travelled to Greater Poland for business. But Dobrzyński was a poor nobleman with a modest kitchen and had no use of a cookbook meant for aristocratic courts, so he gave it to the Tribune, for the benefit of Judge Soplica’s household.[12]

There’s nothing random about this Greater Poland connection. This region of western Poland is where Mickiewicz stayed for a few months in 1831, while an anti-Russian uprising was raging in the Russian partition of Poland. He wished to join the insurgency, but the border between Russian and Prussian partitions was guarded so well that he got stuck in Greater Poland, that is, on the Prussian side. The uprising had been long quelled when Mickiewicz was still visiting the noble manors of the Prussian partition, sightseeing, romancing and writing poetry. Many of the details of everyday life, allegedly typical for Lithuanian nobility, that you will find in Pan Tadeusz are actually the result of the observations the poet made in Greater Poland. And his precious cookbook – “a dear souvenir of righteous customs”, as he wrote in the deleted passage – really did once belong to an Antoni Poniński, who gifted it to Ludwik Skórzewski and whose widow, Honorata Skórzewska, gave it as a present to… no, not to Bartek Dobrzyński, but to Mickiewicz himself, while he was a guest at Kopaszewo.[13]

This was also where he heard the tales of a great banquet of 1812, which Józef Chłapowski, Captain of Kościan, gave in the nearby palace of Turew🔊, to the soldiers of the 1st Light Cavalry Regiment of the Imperial Guard (an elite unit of Napoleon’s army, made up exclusively of Polish noblemen), his son, Dezydery Chłapowski, among them.[14] Mickiewicz would then poetically transfer this feast from Turew, Greater Poland, to Soplicowo, Lithuania, while also enhancing it with an Old Polish menu inspired by a cookery book he had kept as a dear souvenir of his stay in Lady Skórzewska’s manor.

In the Tribune’s Kitchen

The Tribune had precious little time to prepare the feast. The army arrived in Soplicowo in the evening and the ceremonial dinner was to take place in the afternoon of the following day. Such a feat would have been impossible in real life, but in the poem it’s barely an inconvenience. Anyway, the kitchen was bustling with work all night and all day. How was this work organised?

“Among the smoke’s coils, like a white mother-dove, the white cap of the head-chef flashed, gleaming, above.”[15]

Detail of a painting by Wandalin Strzałecki (1884)

Although it was late, | ||

| — A. Mickiewicz, op. cit., Book XI, verses 109–110, 124–132

Original text:

|

So there was one master chef (with the Tribune in this role, obviously), commanding five cooks, who, in turn, shouted orders to scullions, who were doing all the dirty work. If fifty knives were clattering at the same time, then there must have been at least ten scullions to every cook. The Tribune, meanwhile, was just standing in the middle, reading the recipës aloud and making sure they were “carried all out to the letter”: take, chop, pour, boil, take, chop, pour, boil…

Naturally, the master chef must been dressed appropriately for his role:

As the chef, a white apron he tied round his waist, | ||

| — A. Mickiewicz, op. cit., Book XI, verses 111–113

Original text:

|

Again, the white apron didn’t just spring out of the poet’s imagination, for Master Chef Hrechecha is taken straight out of the “Instruction for the Master Chef” contained in Compendium Ferculorum. It reads as follows:

| The master chef should keep his cooks obedient, honest, sober and tidy. […] And he should be setting an example himself, by being neat and clean, sober, attentive, loyal and, most of all, dedicated to his lord and brisk. […] A cook should be tidy, his hair combed, face clean-shaven, hands well-scrubbed, fingernails trimmed, and wearing a white apron; he should be sober, mild-tempered, submissive, quick, well-versed in matters of taste, […] and, above all, willing to serve everyone. | ||

| — S. Czerniecki, op. cit., p. 9–10, own translation

Original text:

|

By the way, it’s quite telling that the word “sober” appears three times in this instruction. It seems that the stereotypical cook of Old Polish times had a tendency to tipple a little too much. The Reverend Jędrzej Kitowicz, as always, describes the problem in a most vivid way:

| Wine […] began to be used in cooking […] One part for the dish, and two parts down the gullet of the cook. And when the cook called for wine, he was telling the truth when he said he needed it for the tongue – but for his own, not for the tongue of beef. And were he to be denied anything he requested, he would ruin the dish on purpose, pretending that he didn’t have the proper ingredients needed to season it. | |||

| — Jędrzej Kitowicz: Customs and Culture in Poland under the Last Saxon King, Oscar E. Swan (trans.), Budapest – New York: Central European University Press, 2019, p. 274

Original text:

|

Painted by an anonymous 17th-century Italian artist

We can also see the issue of ever-drunk kitchen staff in Pan Tadeusz; specifically, at the court of a great lord, Pantler Horeszko:

In the castle but Pantler, Milady, and me, | ||

| — A. Mickiewicz, op. cit., Book II, verses 292–293

Original text:

|

But in the ideally idyllic Soplicowo this would have been unthinkable. Here everything worked like a charm. If a “perfect cook” ever existed, then it must have been none other than Tribune Hreczecha himself. The effect? A perfect Old Polish-Lithuanian banquet, just as Mickiewicz dreamed it, but realised only on the pages of Pan Tadeusz.

So what was this perfect feast like?

Two things a generous lord to a feast can impart, | ||

| — A. Mickiewicz, op. cit., Book XI, verses 152–153

Original text:

|

Plenty there was for sure. The Tribune even allowed to pour melted butter on wood, so it would burn brighter. The choice of meats and fishes could make your head spin. It wasn’t just plenty, it was excess – which wasn’t exactly avoided at lordly banquets. Czerniecki maintained that “melius abundare quam deficere”, or “it’s always better to have too much than too little.”[17] This is how he explained this attitude:

| It is the master chef’s duty […] not to overspend, although a certain degree of overspending is needed, as it highlights the host’s generosity. According to an old proverb, it’s better to incur a thaler’s worth of loss than a halfpenny’s worth of embarrassment. A skilled chef should keep this in mind, not to disgrace his lord with foolish parsimony. | ||

| — S. Czerniecki, op. cit., p. 7, own translation

Original text:

|

An excerpt of the original (1682) edition of Compendium Ferculorum

And what about art? Czerniecki had no doubt that culinary craftsmanship is much more than just a way to satisfy someone’s hunger, greed or vanity. It is a full-blown type of art that you won’t fully appreciate without proper training and education.

| Among the attributes of human nature there is love for diverse flavours, not only out of appetite, but also due to one’s intellect, skill and knowledge. | ||

| — S. Czerniecki, op. cit., p. [VIII], own translation

Original text:

|

So what came out of this marriage of plenty and art? That we shall see in the next post.

References

- ↑ Adam Mickiewicz: Pan Tadeusz, czyli Ostatni zajazd na Litwie: Historia szlachecka z roku 1811 i 1812 we dwunastu księgach wierszem, Lwów-Warszawa-Kraków: Zakład Narodowy im. Ossolińskich, 1921, Book XI, verse 75

- ↑ A. Mickiewicz, op. cit., Book XI, verses 107–108

- ↑ A. Mickiewicz, op. cit., Book II, verses 697–698

- ↑ A. Mickiewicz, op. cit., Book V, verses 427–428

- ↑ A. Mickiewicz, op. cit., Book I, verses 816–817

- ↑ A. Mickiewicz, op. cit., Book XI, verses 133–135

- ↑ A. Mickiewicz, op. cit., Book IV, verse 977

- ↑ A. Mickiewicz, op. cit., Book XI, verses 126–127

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 A. Mickiewicz, op. cit., Poet’s explanatory notes, own translation

- ↑ Turns out, it wasn't the first after all. See: Even Older Polish Cookery for Complete Beginners (note added on 13 May 2024).

- ↑ A. Mickiewicz, op. cit., Book XI, verses 117–118

- ↑ Adam Mickiewicz: Pan Tadeusz, manuscript; quoted in: Jarosław Maciejewski: Mickiewicza wielkopolskie drogi, Wydawnictwo Poznańskie, 1972, p. 313–314; quoted in: Renarda Ocieczek: “Zabytek drogi prawych zwyczajów” – o książce kucharskiej, którą czytywał Mickiewicz, in: Marek Piechota: “Pieśni ogromnych dwanaście…”: Studia i szkice o "Panu Tadeuszu”, Katowice: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Śląskiego, 2000, p. 190

- ↑ Andrzej Kuźmiński: Podróże z Panem Tadeuszem, Pępowo: Stowarzyszenie Lokalna Grupa Działania Gościnna Wielkopolska, 2012, p. 85

- ↑ A. Kuźmiński, op. cit., p. 126

- ↑ A. Mickiewicz, op. cit., Book XI, verses 407–408

- ↑ O stołach i bankietach pańskich, in: Jędrzej Kitowicz: Opis obyczajów i zwyczajów za panowania Augusta III, vol. 3, Poznań: Edward Raczyński, 1840, p. 155

- ↑ S. Czerniecki, op. cit., s. 44

- ↑ S. Czerniecki, op. cit., s. [VIII]

Bibliography

- Maria Barłowska: Jerzy Ossoliński’s legacy to Rome in 1633, in: Silva Rerum, Warszawa: Muzeum Pałacu Króla Jana III w Wilanowie, 17 August 2015

- Stanisław Czerniecki: Compendium ferculorum albo Zebranie potraw, Jarosław Dumanowski, Magdalena Spychaj (eds.), Warszawa: Muzeum Pałacu Króla Jana III w Wilanowie, 2012

- Izabela Jarosińska: Kuchnia polska i romantyczna, Kraków: Wydawnictwo Literackie, 1994

- Andrzej Kuźmiński: Podróże z Panem Tadeuszem, Pępowo: Stowarzyszenie Lokalna Grupa Działania Gościnna Wielkopolska, 2012

- Andrzej Lewandowski: Trojanie w Soplicowie, in: Akant: Miesięcznik literacki, Towarzystwo Inicjatyw Kulturalnych, 28 May 2013

- Marek Piechota: “Pieśni ogromnych dwanaście…”: Studia i szkice o "Panu Tadeuszu”, Katowice: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Śląskiego, 2000

- Zbigniew Jerzy Nowak: Kilka uwag o Wojskim w świetle autografów “Pana Tadeusza”, in: “Pieśni ogromnych dwanaście…”, p. 13–31

- Renarda Ocieczek: “Zabytek drogi prawych zwyczajów” – o książce kucharskiej, którą czytywał Mickiewicz, in: “Pieśni ogromnych dwanaście…”, p. 171–191

| ◀️ Previous | 📜 List of posts | Next ▶️ |

| ⏮️ First | 🎲 Random post | Latest ⏭️ |