Epic Cooking: The Last Old Polish Feast

Epic Cooking Food and Drink in “Pan Tadeusz”, the Polish National Epic |

Epic Cooking

Food and Drink in “Pan Tadeusz”,

the Polish National Epic

With a crash the hall's portals at last open fly, | ||||||

— Adam Mickiewicz: Pan Tadeusz, or The Last Foray in Lithuania: A Tale of the Gentry during 1811–1812, translated by Marcel Weyland, Book XII, verses 1–7

Original text:

|

With these words begins the last chapter, or Book XII, of Pan Tadeusz. Its creation must have been overseen by at least three muses: Calliope (who presides over epic poetry), Thalia (responsible for the comic relief) and Gastronomia (not listed among the classic nine). As we've seen in the previous post, Adam Mickiewicz, the epic poem's author, took inspiration from two old Polish cookbooks. From one (The Perfect Cook by Wojciech Wielądko) he took the title, from the other (Compendium Ferculorum by Stanisław Czerniecki), everything else.

Book XII is almost all about a fictional banquet, said to be the last truly Old Polish feast. It is held by Judge Soplica in an abandoned castle about a mile away from his own manor called Soplicowo. Tribune Hreczecha, ever the Renaissance man, who served as the master chef in Book XI, now replaces his flyswatter with a ceremonial staff indicating that he is now the master of ceremonies. It is he who, in the Judge's name, welcomes and seats the guests, and decides what dishes, in what order and on what tableware are to be served.

There are as many as three occasions for the big ceremonial dinner. First, it's a religious holiday, "the most solemn day of Our Lady of [the] Flowers".[1] Mickiewiczologists can't entirely agree as to the identity of this Catholic solemnity. Some say there is no such holiday, so the poet must have meant Our Lady of the Herbs, that is, Assumption Day, observed on 15 August. They propose various arguments, from historical (in real life, Napoleon invaded Russia only on 24 June 1812) to climatic and botanical ones (the spring of 1812 came late, so no flowers were yet blooming in March). But the poet was quite unequivocal in Book XI that the action was taking place in the springtime rather than in the summer. Besides, Our Lady of the Flowers does exists, as this is an old folk name for the feast of Annunciation, observed on 25 March. On this day, the mother of Jesus gest herself knocked up, while Napoleon (according to Mickiewicz) begins his campaign to knock down the Russian tsar. The former brings hope for salvation of all humanity from sin while the latter brings hope for resurrecting Poland as an independent state. The poem makes no mention of the disaster that Napoleon's invasion of Russia would prove to be; the mood is full of joy and hope until the end.

The second occasion is a triple betrothal; Thaddeus proposes to Sophie, the Notary to Telimena and the Assessor to Tekla Hreczecha, the daughter "not too young, of some at least fifty years,"[2] of the master of today's ceremonies. And finally, the third occasion is the presence of Polish soldiers serving in the French army, including Gen. Dąbrowski, whom the Judge wishes to honour by inviting them to dinner. In line with the general's request, the dinner will feature "Polish cooking", reflecting Old Polish cuisine as imagined by Mickiewicz.

So let's try (as we already once did with an everyday Soplicowo supper) to reconstruct, at least partly, the menu of this exceptional banquet. How? By listing what dishes are mentioned in the poem and then looking them up in Compendium Ferculorum to check how they were made.

What Did They Eat?

When describing the banquet that was going to be "the last Old Polish feast", Mickiewicz hoped to share with his readers the feeling of nostalgia for foodways that had already been gone by his time. What he wanted to convey was, this Old Polish cuisine no longer exists, no one knows these dishes anymore, no one remembers their tastes, even their names now sound unfamiliar. How did he achieve this effect? That's simple: all you need to do is to take a hundred-odd-years-old cookery book and list the quaintest-sounding dish names.

Who now comprehends all these, to our times quite strange, | ||||

— A. Mickiewicz, op. cit., Book XII, verses 144–147, own translation based on Marcel Weyland's

Original text:

|

"It is but a reminder of those famous boards

Once set out in great houses of our ancient lords…"[3]

Painted by Aleksander Orłowski (1st half of the 19th century)

You don't know any of these specialities? Don't worry, Mickiewicz was actually assuming that the readers in his own time wouldn't know them either; heck, he doesn't seem to have known their exact meanings himself. The excerpt above is just a jumble of random words that don't really add up to any meaningful menu. We're going to decipher them in a moment, but first let's see where the poet took them from.

The main body of Compendium Ferculorum (A Collection of Dishes) by Stanisław Czerniecki (pronounced stah-NEE-swahf churn-YET-skee), the cookbook that Mickiewicz loved to read while pining for Polish grub, follows a well-thought-out structure. It is divided into three chapters, each containing one hundred recipes (more or less; the author did cheat with the numbering a little), respectively, for meat dishes, fish dishes, and dairy and other dishes. At the end of each chapter, Czerniecki added ten bonus recipes, as well as one "master chef's secret".

These three "secrets" were recipes that required the highest level of culinary expertise, attainable only by the most skilled of chefs. Czerniecki divulges them as a sort of present for his readers. The first of these secrets is a recipe for a capon in a bottle. The trick was to carefully skin the capon (a well-fattened castrated rooster), put the skin inside a bottle, fill it with a mixture of milk and eggs, and sew it up, then plug the bottle and plunge into boiling water. As the mixture expanded in heat, it made the skin swell and stiffen, producing an illusion of a whole capon fit inside a bottle. The bird's flesh could have been cooked and served separately, but it wasn't about the meat. It was all about the deception, the surprise and making sure that the guests would "not be without great astonishment".[4] Mickiewicz made no use of this particular idea in his poem, but we will come back to the two other secrets later on.

When searching for ideas for his description of the big festive meal, Mickiewicz took something from each of the three chapters, but it was in the third where he found the weirdest-sounding ones. Czerniecki introduces the chapter with the following words:

| In the third chapter, I have included […] jellies, contusas, blancmanges, arcases, almond rings, macaroons […] | ||||

— Stanisław Czerniecki: Compendium ferculorum albo Zebranie potraw, Kraków: w drukarni Jerzego i Mikołaja Schedlów, 1682, p. 92, own translation

Original text:

|

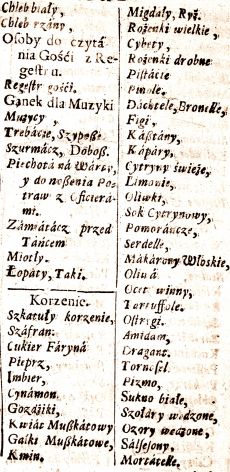

So by now we know where the second line of the aforecited excerpt is coming from. What about the next two? It seems that the idea for these "tragacanths, brignoles and pinoli" came not from any specific recipes, but from the "General Memorandum for the Preparation of a Banquet" that Czerniecki included at the beginning of his book. It was a checklist of things and people that you should have at your disposal before you start preparing a big lordly feast. It opens with a list of various kinds of meat, followed by sundry dairy products, cereals, fruits, vegetables, spices, preserves, different kinds of fish and sugar, as well as kitchen utensils and jobs (including, for example, floor-sweepers equipped with brooms, shovels and wheelbarrows, because, you know, if there's going to be plenty of food, then there's also going to be plenty of leavings). As for the spices, the list covered, among others, the following:

| Saffron, powdered sugar, pepper, ginger, cinnamon, cloves, mace, nutmeg, cumin, almonds, rice, large raisins, cybets, small raisins, pistachios, pinoli, dates, brignoles, figs, chestnuts, capers, […] starch, tragacanth, tornosol [i.e., strips of cloth – or scraps of old underwear, according to Kitowicz[5] – used for dyeing food], musk […] | ||||

— S. Czerniecki, op. cit., s. 4, own translation

Original text:

|

There's not much context here, so it's possible Mickiewicz couldn't even guess what some of these items were supposed to mean. But their meanings, of course, are precisely what we're interested in here. So, without further ado, let's break them down one by one:

Fragment of the "General Memorandum for the Preparation of a Banquet" from Compendium Ferculorum

"Contusa" (Polish: kontuza)

- An insipid mush for the ill, made from overcooked chicken, ground in a mortar into a pulp (hence the name; a contusion is produced in a similar manner after all), passed through a sieve and thinned down with some broth. No aromatics other than parsley. It's rather hard to imagine a dish like this at an opulent feast. Or that you could serve something of such consistency on a platter.

"Arcas" (Polish: arkas)

- Something between fresh cheese and jelly. It was made by boiling sweetened milk and adding lemon juice to curdle it. We're going to come back to this once we get to desserts.

Blancmange (Polish: blemas, blamas)

- A dessert quite similar to the arcas, but fit for Catholic lean days, as it was made from almond milk. The name means "white food" in French, which seems to be a pretty accurate description.

Scrod

- Young cod fish. I used this word to translate the archaic Polish word "pomuchla", which actually referred to Baltic cod of any age, as opposed to cod caught in other seas. We will be returning to fish later on.

Figatelli (Polish: figatele, figatelle)

- The Italian word refers to Corsican dried pork sausage. In Polish, "figatelle" is an archaic word for meatballs, which could be boiled, fried or baked. Often seasoned raisins, they were served as a side to various dishes, including soups.

"Cybets" (Polish: cybety)

- This word appears in Compendium only once, that is, in the "Memorandum", but not in any of the recipes, so it's hard to tell what Czerniecki meant by it. It could possibly refer to civet, fragrance fixative obtained from the glands found near the anus of an African weasel-like animal; or to Muscat-of-Alexandria raisins, known in Italian as zibibbo; or to cubeb pepper.

Musk (Polish: piżmo)

- Just like civet, it's a kind of fragrance fixative, obtained from the glands found near the same body part, only in a different animal, namely the Siberian musk deer. The culinary use of such fixatives was not uncommon, especially in perfumed dishes.

Tragacanth (Polish: dragant)

- Natural gum obtained from the dried sap of Astragalus gummifer. Today also known as E413, it may be used as food additive, for example, to make jellies stiffer.

Pinoli (Polish: pinele, pinole, pinelle)

- Pine nuts. Czerniecki used them interchangeably with pistachios.

Brignoles (Polish: brunele, brunelle)

- Brignoles is a French town famous for its plums and prunes. The Polish word "brunelle" may have referred to dried plums of any kind.

So far, all we've got are just individual ingredients. If we want entire dishes, we've got to check out other verses of the poem. As in any Polish dinner, we will start with the soups.

Soups

In all of Pan Tadeusz I've counted five distinct kinds of this crucial element of Polish cuisine. We've already discussed two of them, the beer soup and the Lithuanian cold borscht, in previous posts. Elsewhere in the epic, when Thaddeus's would-be father wanted to propose to a great lord's daughter, he was served "black gruel",[8] or czernina (blood soup, which is, incidentally, more of a Greater Poland speciality than a Lithuanian one), as a sign of refusal. Naturally, this soup's symbolism meant that it couldn't be served at a betrothal dinner.

An unspecified soup is also used by the poet in a rather bawdy joke. You see, in Polish, the word "zupa" ("soup") rhymes with "dupa" ("arse"), so Mickiewicz used the former to avoid mentioning the latter. Translating the pun into English is, of course, a challenge; this is how Mr. Marcel Weyland has dealt with it:

"I have heard, he had under the bishop's curse passed; | ||||

— A. Mickiewicz, op. cit., Book XII, verses 396–398

Original text:

|

But the description of the banquet we're discussing today begins with two soups taken straight from Compendium Ferculorum:

And the house-servants entered in pairs, in good line, | ||||

— A. Mickiewicz, op. cit., Book XII, verses 137–142

Original text:

|

One Mickiewiczologist who intentionally refrained from trying to understand the meanings of these "mysterious dishes", so as not to let the magic of the "cryptic flavours" escape, announced that from the time of Mickiewicz onward, "these very two soups – white and red! – will forever stand on the national table, no matter what."[9] The problem is that if you do try and decipher them (and this is exactly what we're about to do), then this patriotic vision of two soups in Poland's national colours will fall apart like a house of cards. Let's begin with the "royal borscht" and see if it was really red. As it happens, it's the first recipe in the third chapter of Compendium Ferculorum.

| Take thin rye-bran borscht [i.e., fermented rye meal]; add some dried fish, be it pike or vimba; dried salmon; Danubian carp; smoked or fresh beluga; dried sturgeon; a whole onion, which you will discard before serving; soaked herrings, either Danubian or marine; dried mushrooms; fine buckwheat; and cumin. Boil it all together, salt to taste. Serve it in a bowl, it will be good. | ||||

— S. Czerniecki, op. cit., s. 71, own translation

Original text:

|

It will be good, for sure, but hardly red. It's not the familiar red beetroot borscht, but rather something modern Poles would call either "barszcz biały" ("white borscht") or "żurek" ("sour soup"), made from fermented flour-and-water mixture (or thinned sourdough, if you will). It used to exist in two versions: the festive one, cooked on smoked-meat stock and served on sausage, bacon and eggs, is still very much around. The Lenten version, with salted herring, once very common, is now somewhat forgotten. What Czerniecki calls "royal borscht" is the Lenten variant, but in a royal guise, so apart from the cheap herring, there are also more upscale fish species, such as pike, salmon and sturgeon. Mushrooms are there too, probably even more than two ("two mushrooms into borscht" is a Polish idiom expressing excess), as well as the exotic cumin.

And what about the other soup? The mention of a gold coin, pearls and "a secret old recipe" leaves no doubt that it's Czerniecki's third master chef's secret. But if you read the recipe carefully, you will see that it's no so much a banquet dish, but another concoction for the ill.

| This is an excellent secret, tried on the ill and those despairing about their health, which you will prepare in the following manner: Take a hind quarter of a ram, a capon, four partridges, fresh meaty venison and beef, all unplucked, unwashed and unsalted. Spit-roast them all on a small fire without basting and remove once they are well done. Poke or cut them quickly with a knife and press out the juices into a glass vessel. Put a string of pearls and a red ducat inside and wrap the vessel tightly in bladder and canvas. Place the bundle in cold water, bring the water to boil and cook for four hours. Then remove and unwrap the vessel and take it to the patient. Let him drink a spoon and a half, while still warm, on an empty stomach and cover him with blankets to let him sweat. Reserve the red ducat and the pearls. This secret should not be used more than once in one illness. If the patient is sweating, he will, God willing, experience amelioration. | ||||

— S. Czerniecki, op. cit., s. 96, own translation

Original text:

|

"The Old-Polish clear broth, prepared with great art,

Into which, by a secret old recipe, threw

The Tribune a gold coin and of pearls not a few"[10]

Detail of a painting by Jan Brueghel the Elder (1618).

You can see that this was a cure for the well-to-do only. All we're getting out of an entire stag, an ox, a quarter of a ram, four partridges and one capon is one and a half tablespoons of meat juice that we're supposed to let the patient quaff to make him sweat. Sounds rather like some kind of homeopathic scam, doesn't it? It's even more suspicious, if you consider what happens to the ducat and the pearls that the chef would have said he'd needed for this elixir. In any case, it doesn't seem these ingredients had any influence on the preparation's medicinal properties, flavour or even colour. If you had thought that, if the borscht hadn't turned out to be the red soup, then perhaps it was this red-ducat broth, then think again. The Polish red ducat wasn't actually red in colour, it was golden; besides, gold doesn't dissolve in water (unless it's royal water, or aqua regia, but that wouldn't be really fit for consumption). It's more likely that, like any other good broth, this one, even if cooked without the gold coin, would have been golden in colour – that is, neither white nor red.

For the purpose of our reconstruction, though, I suggest we take another of Czerniecki's broth recipes. A good dinner broth. Just like the one that opens the first chapter of the Compendium.

| Polish broth is to be made as follows: Take beef or veal, a hazel grouse or a partridge, pigeons or any other meat that can be boiled for broth. Soak the meat, salt it well, place in a pot and scald with hot water. Let the water stand for some time, then strain back onto the meat. Add parsley, butter, salt, skim the scum, and when well cooked, serve hot. You should also remember, lest the broth smells like water and wind, to add parsley or dill, onion or garlic, mace or rosemary, or peppercorns according to your taste. | ||||

— S. Czerniecki, op. cit., s. 13, own translation

Original text:

|

Now, this is the kind of broth that you can still see on many a Polish table every Sunday! This recipe seems quite modern in that, unlike many other Old Polish dishes, it's quite moderate in terms of exotic spices (only mace and pepper!), while making use of familiar herbs, like parsley, dill and rosemary. The one thing does seem to be missing are the now mandatory noodles. But noodles aren't the only possible soup garnish and as we already know that there were meatballs on the menu, then why not serve them together with the broth? So now let's see a recipe for the figatelle.

| Take some veal or a capon, beef or game, or fresh lean pork. Remove the veins and chop up finely. Take beef, wether-mutton or venison tallow, remove the veins, chop up as finely as you can. Grate or chop finely some white bread. Mix it all together with a few eggs. Add pepper and nutmeg. Make any meatballs you like, big or small, boiled or baked, and if you want, you can also add raisins, large, small or both, according to your need. Cook them in boiling water. If you want to serve them alone, then garnish with parsley. And if you want to serve them alongside another dish, then add them when already cooked. | ||||

— S. Czerniecki, op. cit., s. 16, own translation

Original text:

|

Fish Dishes

Big aristocratic banquets often lasted for at least a few days. Considering the frequency of lean (fasting) days (every Wednesday, Friday and Saturday), there was no way for the feat not to overlap with a lean day. On such days the menu was modified to include fish, but no meat of any land animals. This why Compendium Ferculorum has an entire chapter devoted exclusively to fish dishes. The banquet in Pan Tadeusz is condensed to just one day, but the menu contains both meat and fish items. You may have already notice that of the two soups, one was meat-based while the other was a fish soup. So let's continue with this convention and have one fish dish to every meat serving on our menu. And, since the poet devoted more attention to fish, let's start with this.

And those fish! Great smoked salmon from Danube afar, | ||||

— A. Mickiewicz, op. cit., Book XII, verses 148–151

Original text:

|

Again, this is just an enumeration of fish species taken directly from the "General Memorandum". The full catalogue goes like this:

| Salmon, fresh and dried, Danzig and Danubian; sterlet; sturgeon, fresh, salted and smoked; trout; barbel; stone loach; gudgeon; grayling; vimba, fresh and dried; bullheads; eels, fresh and dried; various freshwater fish; salted fish; beluga, fresh, salted and smoked; herring; Venetian caviar, Turkish caviar; Danubian herring, smoked herring; flounder; dried plaice; luce, pike, pickerel, hurling pick, gilthed; carp, Danubian, young and platter-sized; perch; crucian; bream; tench; stockfish, cod, scrod; oysters; turtles; escargots; crayfish. | ||||

— S. Czerniecki, op. cit., p. 5, own translation

Original text:

|

Some of the species here further subdivided according to age and size. In traditional Polish terminology, the pike, for example, ranges from the obłączka (smallest) to szczupak półmiskowy ("platter-sized"), szczupak łokietny ("cubit-long"), szczupak podgłówny ("sub-main") to szczupak główny ("main", the largest). These terms used have their equivalents in English: gilthed, hurling pick, pickerel, pike and luce.

So we've got quite a few fish species, but what about fish dishes? Here Mickiewicz was a somewhat less specific. He did mention one delicacy, though, which was served at the end of the dinner as the master chef's pièce de résistance.

Last, a master-chef's tour de force comes into view: | ||||

— A. Mickiewicz, op. cit., Book XII, verses 152–154

Original text:

|

Obviously, that's the second "secret" from the Compendium. This one, for a "whole, uncut fish, cooked in three ways", except that in Czerniecki's recipe it was middle that was boiled, the head was fried and the tail, roasted.[12] Not any fish will do here. It must both appropriately dignified and long, which means a mature pike is the best choice. The trick is rather simple: all you need to do is to spit-roast the fish over low-burning coals. The part that's meant to be boiled must be wrapped in cloth that is constantly doused with salted water with vinegar. The part that's supposed to be fried is basted with oil and sprinkled with flour. And the part that's meant to be roasted is roasted. And here's the full recipe as written by Czerniecki:

| Take a pike, as large as you want, remove the scales near the head and tail, but leave them in the middle. Gut it and impale on a spit. Wrap a piece of cloth around the middle part with the scales and secure with strings. Dampen the cloth with salted wine vinegar. Salt the head and the tail as well, and turn the spit over low flame. Keep vinegar boiling in a clay pot and pour it often often on the cloth. Baste the head early on with oil or butter, sprinkle with wheat flour and repeat this several times so that keep it frying. And when the tail starts to brown, then baste it too, but don't sprinkle with flour. And when you deem the fish done, remove it from the spit and unwrap the cloth. You will have a pike that is fried, boiled and roasted. | ||||

— S. Czerniecki, op. cit., s. 67–68, own translation

Original text:

|

Piotr Klepacz and Tomasz Welter with a pike made ready for roasting / frying / boiling

This was the only fish dish mentioned in Book XII, but not the only one in all of Pan Tadeusz:

[…] Any Muscovite general puts on a great show, | ||||

— A. Mickiewicz, op. cit., Book IV, verses 402–403

Original text:

|

Mickiewicz only used the pike in saffron sauce in a simile, without paying any more attention to it, but in Old Polish times it was one of the nobility's favourite fish-based specialities. Saffron, in general, was one of their favourites seasonings; Czerniecki described Polish cookery as "saffrony and peppery".[13] But since we've already used pike in the previous dish, let's now have salmon instead, which – again, according to Czerniecki – "is in our Poland of the most subtle flavour." Salmon in "royal saffron sauce" is the first recipe in the second chapter of the Compendium.

| Take a salmon, gut it and remove the scales, cut out the backbone, impale the steaks on pins. Dice and julienne some parsley roots. Boil it all in a cauldron with a good amount of salt. And once it is done, remove from the flame, strain, wash away the salt. And just before serving add any kind of coulis [i.e., thick vegetable sauce] you have, wine, a little wine vinegar, sugar to taste, pepper, saffron, cinnamon, large raisins and a sliced lime. Boil some more and taste; if not salty enough, you may add some of the broth that you cooked the salmon in. | ||||

— S. Czerniecki, op. cit., s. 46, own translation

Original text:

|

And for the third fish dish, let's take that one of Czerniecki's recipes that will allow us to use up the carp and the pine nuts that we already have in store.

| Gut scaled fish and cut into steaks. Chop finely some onions and parsley roots. Put it all in a pot, salt to taste. Add some shelled pine nuts, butter or olive oil, pepper and nutmeg. Cook it and serve while hot. | ||||

— S. Czerniecki, op. cit., s. 51, own translation

Original text:

|

Meat Dishes

Painted by Alexander Adriaenssen (17th century).

When composing the meaty part of our menu, we'll need to make even more use of our own imagination, because the poet didn't mention any specific meat dish in the banquet's description. We only know from the part about the meal's preparation that meat was plentiful, both in terms of quality and diversity.

Yet others, huge roasts onto enormous spits drag | ||||

— A. Mickiewicz, op. cit., Book XI, verses 138–149

Original text:

|

As you can see, most of this flesh was roasted. What's interesting, Czerniecki included almost no instructions for roasting in his cookbook. He must have thought the procedure too simple to even bother writing about; you just stick the animal on a spit and turned over a flame, that's all. Most of his recipes are for boiled or stewed meats. But we're lucky to have ten recipes from his addendum to the first chapter, all for roast condiments. The author proposes condiments, or rather sauces, made from mushrooms, garlic, mustard seeds, juniper berries, cauliflower, capers, limes, anchovies, oysters… But let's pick the one that is the simplest to make and also the most typically Polish – the onion condiment.

Hussar-style roast beef as made by Ms. Monika Śmigielska, author of the blog "Kuchenny Kredens", where you can find a more up-to-date recipe (in Polish).

| Chop fresh onion as finely as poppy seeds, mix it with fresh butter and pepper, and stuff into incisions cut into freshly roasted beef. Serve while hot. | ||||

— S. Czerniecki, op. cit., s. 42, own translation

Original text:

|

Roast beef that is sliced not all the way through, with onion filling stuffed into the pockets, is a dish that is still very much of Polish cuisine today. It was given its current name, "hussar-style beef", in the 19th century, when the stripes of yellowish stuffing reminded our ancestors of the decorative frogging on hussar uniforms.

We know from the poem that poultry was also served. And we haven't yet made any use of the caviar that we know was there. As it turns out, roast capon goes perfectly with caviar, at least if we're to believe Czerniecki. Here's the last recipe from the first chapter of his cookbook:

| Roast a good capon, slice it while hot. Take some washed caviar, mix it with unsalted butter and stuff into the capon, season with pepper, serve hot. | ||||

— S. Czerniecki, op. cit., s. 37, own translation

Original text:

|

I'll leave it up to you whether to use Venetian or Turkish caviar.

And finally, to use up the prunes, let's have a dish of stewed meat, say veal. This is Czerniecki's recipe for a prune stew:

| Take some […] veal, […], clean it and cut into pieces, chop finely some onion and parsley root. Put it all in a pot with good butter and salt. Cook it and when it's almost done, add prunes and sugar, as well as pepper, nutmeg and a little wine vinegar, then serve. | ||||

— S. Czerniecki, op. cit., s. 21, own translation

Original text:

|

Desserts

It's time for dessert at last. For this course we're going to have an "arcas" and a blancmange (but you knew that already). Let's start with the "arcas", which, for the record, is an English word I made up for want of any better (other than "milk jelly") rendering of the Polish term, "arkas", which, itself, is of unclear etymology.

| Take as much fresh milk as you want, put on a flame in a fine vessel, add sugar, and when it's starting boil, squeeze in one lemon or pour in a spoon of wine vinegar. And once it curdles, pour it in little baskets to strain, so that only the thicker matter stays and the subtle matter oozes away. Remove the jelly from the basket onto a plate covered with some rose water, sprinkle with sugar and serve. You may also add saffron to the milk, if you want. | ||||

— S. Czerniecki, op. cit., s. 91, own translation

Original text:

|

Czerniecki doesn't mention it in this recipe, but if you want to make sure the jelly will settle, you may want to stiffen it with a little tragacanth.

We're still keeping with the rule that for each recipe that isn't lean, we're also having one that is. So now let's make a purely vegan blancmange. Notice that the recipe makes use of the aforementioned musk, which we may to make sure the aroma doesn't fade away.

| Take some [vegetable] broth. Grind blanched almonds very finely in a mortar and dissolve them in the broth. Strain the liquid through a fine cheesecloth and pour into a bowl. But first season the broth with fresh lemons, wine, cinnamon, cloves and musk, and then use it to dissolve the almonds. | ||||

— S. Czerniecki, op. cit., s. 88–89, own translation

Original text:

|

By the way, Czerniecki also suggests another recipe for lean (but non-vegan) blancmange, which is settled with fish aspic.

The Centrepiece Masterpiece

Mickiewicz didn't devote nearly as much space to the dishes as he did to the tableware and in particular to the huge silver-and-porcelain centrepiece.

The guests meanwhile, awaiting their meal in the hall, | ||||

— A. Mickiewicz, op. cit., Book XII, verses 25–27

Original text:

|

So what exactly is a centrepiece? Imagine the familiar stand for salt and pepper shakers. Sometimes you may come across more elaborate versions with cruets of vinegar and olive oil, and a napkin holder. And now imagine this kind of stand, but blown up to giant proportions, so that is takes up half of the table, and with rich ornamentation at that. This is what a centrepiece, also known by the French term, surtout de table (literally, "all over the table"), is.

The centrepiece which the Tribune dug out from the storage was enormous even by Baroque standards. On a round tray the size of a carriage wheel[16] there stood at least thirty porcelain figurines "dressed in Polish apparel".[17] These figures represented a scene from a typical local legislature of Old Polish times – an election campaign, a vote tally, an unsuccessful veto, the winner's joy and the loser's wife's grief. I won't be going into details here; if you want, you can read the Tribune's description of the scene, to which Lord Chamberlain quipped, "that election's quite curious, we grant, but just now we are hungry; it's food that we want."[18]

"The guests meanwhile, awaiting their meal in the hall,

With surprise let their gaze on the centrepiece fall, […]

Taken out of the strongroom today for this meal,

The table's centre graced like a huge carriage wheel."[19]

Illustration by Kazimierz Mrówczyński (1898).

Let's focus instead on the foodstuffs that were displayed on this centrepiece, even if they were there more for decoration than for eating – just like fondant icing on modern-day layer cakes (such as the wonders that my sister makes, for example). So now brace yourselves for a longer piece of anapestic tetrametre (I believe it is really worth reading, though).

"Round the edge of the platter stood neatly displayed

Scores of little blown figures of porcelain made…"[20]

A Meissen-porcelain centrepiece (ca. 1760), Museum of Art, Rhode Island School of Design.

Rim to rim this grand object, replete with the glow | ||||

— A. Mickiewicz, op. cit., Book XII, verses 35–40, 159–184

Original text:

|

"Warmed by the heat of the day

The light sugary ices had melted away…"[21]

A rosemary bush covered with whipped-cream "foam" (which has already partly trickled down) and surrounded with cream-filled wafer tubes, the work of Ms. Marta Stelmach (2013).

To perfection a winter's cold landscape portrayed; With a black wood, enormous, of confiture made, By whose edge stood, in hamlets and settlements, homes Not with frost covered, rather with sugary foams

A winter landsape made out of "sugary foams", that is, sweetened whipped cream, is yet another Baroque idea for a culinary illusion taken from Czerniecki's Compendium. In the original version the whipped cream was supposed to be pour on a rosemary bush surrounded with wafer cream rolls. The whole thing was meant to look like an evergreen tree covered with heavy snow with cones lying on the ground. And here's the recipe:

| Take as much thick sweet cream as you need. Add crushed sugar. Whip it in a can until foam is made. […] You may […] pour the foam on a rosemary bush that you can set up this way: cut a loaf of rye bread in half. Remove the crumb from one half, spread inside with butter and put it on an [upside-down] bowl so that the butter sticks it and the bread together well. And into this bread stick a rosemary bush and pour the foam onto it, surround it with cream rolls, sprinkle with sugar and serve. | ||||

— S. Czerniecki, op. cit., s. 90, own translation

Original text:

|

"The guests to the courtyard repaired,

Having finished their ices, to taste the cool air."[22]

Saffron ice cream by Bogdan Gałązka, Gothic Restaurant, Malbork.

After some time, this foam would trickle down from the bush, producing the illusion of thaw. Winter was gone, spring nd summer were here. The foam would also uncover a dark forest made of fruit preserve, fields of buckwheat made from chocolate, apple and pear trees made from, I don't know, some apple-and-pear mousse? And saffron wheat fields, which I suppose doesn't mean naked crocus threads, but some kind of paste dyed yellow with saffron. And if not long later "the grain, painted gold, slowly melt[ed] while absorbing the warmth of the hall",[23] then it surely must have been saffron ice cream. That would have been a truly Baroque twist: snow imitated by lukewarm cream "foam" and summer crops made from ice cream! Sadly, Czerniecki provides no ice cream recipe. But I do know that you can get delicious saffron ice cream (with ground orchid tubers, which give it a peculiar fudgy texture) at the Gothic Restaurant in the Malbork Castle. I'd say this treat alone is a good enough reason to visit Malbork, but the largest brick Gothic castle in the world is in itself a sight to behold.

At the end all that was left were cinnamon canes and laurel branches that were somehow covered in cumin seeds. I'm not sure whether these branches would have made a good snack. I'd rather imagine, in this role, some kind of cumin or caraway-flavoured bread sticks.

Anyway, one thing is crucial: to have an audience that will be able to appreciate this art of culinary illusion. It seems that the Tribune, alas, wasn't so lucky.

The guests neither inquired what this dish might be called, | ||||

— A. Mickiewicz, op. cit., Book XII, verses 155–158

Original text:

|

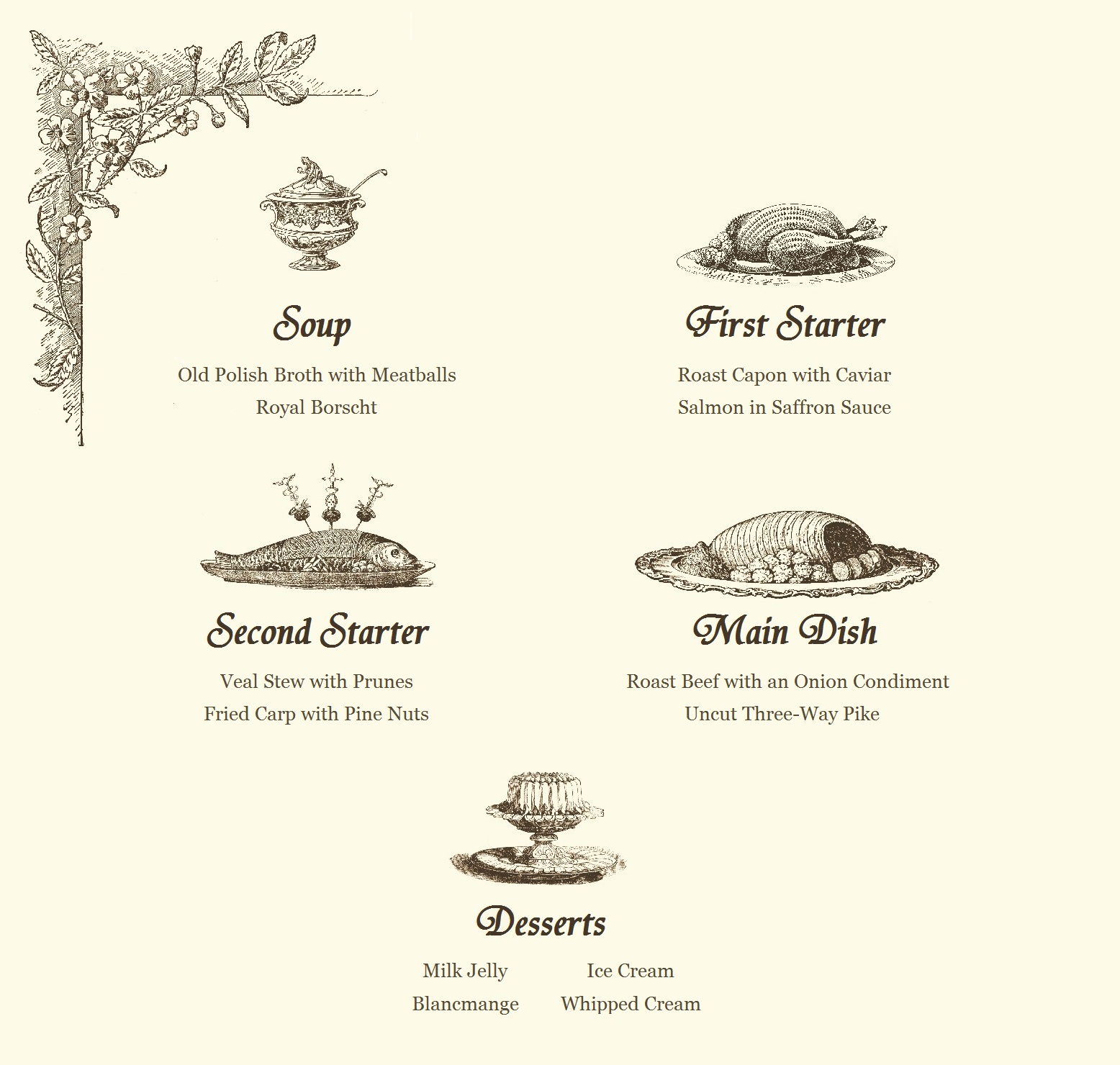

Full Menu

References

- ↑ Adam Mickiewicz: Pan Tadeusz, or The Last Foray in Lithuania: A Tale of the Gentry during 1811-1812, translated by Marcel Weyland, Book XI, verses 153–154

- ↑ A. Mickiewicz, op. cit., Book XI, verse 669

- ↑ A. Mickiewicz, op. cit., Book XII, verses 195–196

- ↑ S. Czerniecki, op. cit., s. 44

- ↑ Jędrzej Kitowicz: Customs and Culture in Poland under the Last Saxon King, Oscar E. Swan (trans.), Budapest – New York: Central European University Press, 2019, p. 270

- ↑ A. Mickiewicz, op. cit., Book XII, verse 143

- ↑ A. Mickiewicz, op. cit., Book XII, verse 397

- ↑ A. Mickiewicz, op. cit., Book II, verse 282; Book X, verse 585

- ↑ Izabela Jarosińska: Kuchnia polska i romantyczna, Kraków: Wydawnictwo Literackie, 1994, p. 208–209, own translation

- ↑ A. Mickiewicz, op. cit., Book XII, verses 139–141

- ↑ A. Mickiewicz, op. cit., Book XII, verse 148

- ↑ S. Czerniecki, op. cit., s. 67

- ↑ S. Czerniecki, op. cit., s. 9

- ↑ A. Mickiewcz, op. cit., Book XI, verse 147

- ↑ A. Mickiewicz, op. cit., Book XI, verses 138–139

- ↑ A. Mickiewicz, op. cit., Book XII, verse 34

- ↑ A. Mickiewicz, op. cit., Book XII, verses 42–43

- ↑ A. Mickiewicz, op. cit., Book XII, verses 122–123

- ↑ A. Mickiewicz, op. cit., Book XII, verses 25–26, 33–34

- ↑ A. Mickiewicz, op. cit., Book XII, verses 41–42

- ↑ A. Mickiewicz, op. cit., Book XII, verses 159–162

- ↑ A. Mickiewicz, op. cit., Book XII, verses 488–489

- ↑ A. Mickiewicz, op. cit., Book XII, verses 174–175

Bibliography

- Stanisław Czerniecki: Compendium ferculorum albo Zebranie potraw, Jarosław Dumanowski, Magdalena Spychaj (eds.), Warszawa: Muzeum Pałacu Króla Jana III w Wilanowie, 2012

- Jarosław Dumanowski, Katarzyna Dumanowska: Słownik, in: Stanisław Czerniecki: Compendium ferculorum albo Zebranie potraw, 2012, p. 182–206

- Jarosław Dumanowski: Tatarskie ziele w cukrze, czyli Staropolskie słodycze, Warszawa: Muzeum Pałacu Króla Jana III w Wilanowie, 2013

- Izabela Jarosińska: Kuchnia polska i romantyczna, Kraków: Wydawnictwo Literackie, 1994

- Luigi Marinelli: O "zagadce" Najświętszej Panny Kwietnej: przyczynek do Mickiewiczowskiej "mariologii", in: Pamiętnik Literacki: czasopismo kwartalne poświęcone historii i krytyce literatury polskiej, 91/3, Warszawa: Instytut Badań Literackich PAN, 2000, p. 201–208

| ◀️ Previous | 📜 List of posts | Next ▶️ |

| ⏮️ First | 🎲 Random post | Latest ⏭️ |