Difference between revisions of "Is Poolish Polish?"

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{data|?? ?? 2021}} | {{data|?? ?? 2021}} | ||

<nomobile>[[File:Bagietka 1.jpg|thumb|Cross-section of a baguette]]</nomobile> | <nomobile>[[File:Bagietka 1.jpg|thumb|Cross-section of a baguette]]</nomobile> | ||

| − | If you ever happen to bake your own bread, then you may have heard of a yeast starter called poolish. And you have heard of poolish, then you may have also heard that | + | If you ever happen to bake your own bread, then you may have heard of a yeast starter called poolish. And you have heard of poolish, then you may have also heard that – as its name implies – it's a remarkable example of Polish contribution to the development of global baking. But is it? This is the question we're going to deal with today. |

<mobileonly>[[File:Bagietka 1.jpg|thumb|Cross-section of a baguette]]</mobileonly> | <mobileonly>[[File:Bagietka 1.jpg|thumb|Cross-section of a baguette]]</mobileonly> | ||

| Line 9: | Line 9: | ||

Ever since people domesticated cereals (or maybe it was the other way around), they have known that if you grind the grains down into flour, then mix the flour with water into dough and bake it, then you'll get a flat, brittle bread like roti, pita or matzo. But if you leave the dough in a warm place for a few hours before baking it, then it will start to bubble and rise; and if you then bake it, the bread will be soft, fluffy, pleasantly tart and aromatic. Beer, another cereal product, has been known about as long as bread. And it's been also known for a long time that if you gather the froth from the surface of fermenting wort and add it to the bread dough, then it will rise faster. | Ever since people domesticated cereals (or maybe it was the other way around), they have known that if you grind the grains down into flour, then mix the flour with water into dough and bake it, then you'll get a flat, brittle bread like roti, pita or matzo. But if you leave the dough in a warm place for a few hours before baking it, then it will start to bubble and rise; and if you then bake it, the bread will be soft, fluffy, pleasantly tart and aromatic. Beer, another cereal product, has been known about as long as bread. And it's been also known for a long time that if you gather the froth from the surface of fermenting wort and add it to the bread dough, then it will rise faster. | ||

| − | <nomobile>[[File:Poolish.jpg|thumb|left|upright=.7|Poolish | + | <nomobile>[[File:Poolish.jpg|thumb|left|upright=.7|Poolish – above, freshly mixed; below, risen]]</nomobile> |

Centuries later, once microscopes were around, the bubbles that cause the dough to rise were shown to be produced by microörganisms. Oversimplifying, there are two kinds of them. One kind is lactic-acid bacteria, which eat the sugars present in the flour, excreting carbon dioxide and lactic acid. Bacteria like these are also responsible for milk going sour (hence their name: "lactic" means "milk", "acid" means "sour") and for cabbage turning into sauerkraut. In bread, the carbon dioxide produces the bubbles which make the bread fluffy, while the lactic acid gives the bread its specific tart flavour. And yes, the dough which is left for bacteria to make it sour is called sourdough. | Centuries later, once microscopes were around, the bubbles that cause the dough to rise were shown to be produced by microörganisms. Oversimplifying, there are two kinds of them. One kind is lactic-acid bacteria, which eat the sugars present in the flour, excreting carbon dioxide and lactic acid. Bacteria like these are also responsible for milk going sour (hence their name: "lactic" means "milk", "acid" means "sour") and for cabbage turning into sauerkraut. In bread, the carbon dioxide produces the bubbles which make the bread fluffy, while the lactic acid gives the bread its specific tart flavour. And yes, the dough which is left for bacteria to make it sour is called sourdough. | ||

| Line 17: | Line 17: | ||

A method, therefore, was needed to somehow rejuvenate this old yeast. And this is why pre-ferments were invented. The idea is to effect preliminary fermentation and let new generations of yeast to bud out from the old ones. Only then comes the second phase of fermentation whose purpose is to rise the dough with the young population of yeast. Pre-ferments come in several kinds, such as the Italian ''biga'' (used in production of ciabattas) or the English sponge (used to make hamburger buns). But what we're interested in is the highly-hydrated pre-ferment, in which flour and water are mixed in equal proportion by weight, producing a runny starter similar in its consistency to pancake batter. This method is mostly used in preparing the dough for baguettes and other typically French rolls. And this is the method which is known by the word "poolish". Phew! | A method, therefore, was needed to somehow rejuvenate this old yeast. And this is why pre-ferments were invented. The idea is to effect preliminary fermentation and let new generations of yeast to bud out from the old ones. Only then comes the second phase of fermentation whose purpose is to rise the dough with the young population of yeast. Pre-ferments come in several kinds, such as the Italian ''biga'' (used in production of ciabattas) or the English sponge (used to make hamburger buns). But what we're interested in is the highly-hydrated pre-ferment, in which flour and water are mixed in equal proportion by weight, producing a runny starter similar in its consistency to pancake batter. This method is mostly used in preparing the dough for baguettes and other typically French rolls. And this is the method which is known by the word "poolish". Phew! | ||

| − | <mobileonly>[[File:Poolish.jpg|thumb|upright|left|Poolish | + | <mobileonly>[[File:Poolish.jpg|thumb|upright|left|Poolish – above, freshly mixed; below, risen]]</mobileonly> |

== Let Them Eat… What Exactly? == | == Let Them Eat… What Exactly? == | ||

Revision as of 21:02, 3 August 2021

If you ever happen to bake your own bread, then you may have heard of a yeast starter called poolish. And you have heard of poolish, then you may have also heard that – as its name implies – it's a remarkable example of Polish contribution to the development of global baking. But is it? This is the question we're going to deal with today.

But for those who haven't heard of poolish, let's first explain what it is exactly. Poolish is a kind of highly-hydrated pre-ferment. Okay, if that didn't help, then let's start from the beginning.

Grain, Yeast, Beer and Bread

Ever since people domesticated cereals (or maybe it was the other way around), they have known that if you grind the grains down into flour, then mix the flour with water into dough and bake it, then you'll get a flat, brittle bread like roti, pita or matzo. But if you leave the dough in a warm place for a few hours before baking it, then it will start to bubble and rise; and if you then bake it, the bread will be soft, fluffy, pleasantly tart and aromatic. Beer, another cereal product, has been known about as long as bread. And it's been also known for a long time that if you gather the froth from the surface of fermenting wort and add it to the bread dough, then it will rise faster.

Centuries later, once microscopes were around, the bubbles that cause the dough to rise were shown to be produced by microörganisms. Oversimplifying, there are two kinds of them. One kind is lactic-acid bacteria, which eat the sugars present in the flour, excreting carbon dioxide and lactic acid. Bacteria like these are also responsible for milk going sour (hence their name: "lactic" means "milk", "acid" means "sour") and for cabbage turning into sauerkraut. In bread, the carbon dioxide produces the bubbles which make the bread fluffy, while the lactic acid gives the bread its specific tart flavour. And yes, the dough which is left for bacteria to make it sour is called sourdough.

The other kind is a bunch of single-celled fungi found in the froth from beer wort and called yeast. The yeast eats sugar, excreting carbon dioxide and ethyl alcohol. Yeast like this is also responsible for producing wine, mead and vodka. In bread, the carbon dioxide makes the bread fluffy, while the alcohol mostly evaporates during baking (which means you can't get drunk on bread; tough luck). Bakers, as we've already seen, used to obtain their yeast from breweries and add it to the starter for their dough (not sour at all).

The year 1842 saw the brewing of the world's first lager in Pilsen (now Plzeň, Czech Republic). Lager is a lower-fermentation beer, which means that the yeast, once done, sinks to the bottom of the vat rather than float to surface. Pilsner-type lager caught Europe by the storm, which had the unexpected side-effect of bakers no longer having access to a source of fresh yeast, as there was nothing to collect from the surface of the lager brew. And fresh yeast was indispensable. In the case of sourdough, it's common to leave some of it to kick-start the next batch, with the resulting flavour only getting better every time. This approach doesn't work with yeast, though, as old yeast gives bread a rather unpleasant, stale aroma.

A method, therefore, was needed to somehow rejuvenate this old yeast. And this is why pre-ferments were invented. The idea is to effect preliminary fermentation and let new generations of yeast to bud out from the old ones. Only then comes the second phase of fermentation whose purpose is to rise the dough with the young population of yeast. Pre-ferments come in several kinds, such as the Italian biga (used in production of ciabattas) or the English sponge (used to make hamburger buns). But what we're interested in is the highly-hydrated pre-ferment, in which flour and water are mixed in equal proportion by weight, producing a runny starter similar in its consistency to pancake batter. This method is mostly used in preparing the dough for baguettes and other typically French rolls. And this is the method which is known by the word "poolish". Phew!

Let Them Eat… What Exactly?

Now that we know what poolish is, let's see how the French have learned to make it. We can start by looking at what can be gleaned from the Internet. Here's what one French culinary website has to say on the topic:

| Originally, poolish was invented to economise on industrially-produced yeast, which was expensive at the time when it was new on the market. Today this is no longer the case and the method is employed for its other advantages. This practice originated in Poland and it was Viennese bakers who introduced it in France for Marie Antoinette. | ||||

— Pain Poolish ou Pouliche, in: La cuisine de Fabrou, own translation

Original text:

|

Seems legit, doesn't it? After all, Marie Antoinette, an Austrian-born queen of France, is famous for her expertise in baked goods and for her piece of advice that those who can't afford bread should eat cake instead. Right? Well, not really, as it turns out. Firstly, the way this quotation is commonly rendered into English is quite loose, because what Marie Antoinette actually talked about was not cake, but brioche ("qu’ils mangent de la brioche"), a sweet bun made from dough rich in eggs and butter. The cake version must have spread in the English language before the brioche became popular in the English-speaking world.

And secondly… Marie Antoinette never really said anything like that. This sentence was originally attributed to an unspecified princess by Jean-Jacques Rousseau in an anecdote of his device. Back then, Marie Antoinette was ten years old and not even thinking about moving to France. It was only long after her death that the gibe was taken from the anonymous princess's mouth and put into the French queen's – most likely to provide some justification for why she'd been guillotined. Interestingly, in Samuel William Orson's translation of Rousseau's Confessions it's neither brioche nor cake, but pastry!

| I furnished myself from time to time with a few bottles to drink in my own apartment; but unluckily, I could never drink without eating; the difficulty lay therefore, in procuring bread. […] I could not bear to purchase it myself; how could a fine gentleman, with a sword at his side, enter a baker’s shop to buy a small loaf of bread? it was utterly impossible. At length I recollected the thoughtless saying of a great princess, who, on being informed that the country people had no bread, replied, “Then let them eat pastry!” | ||||||

— Jean-Jacques Rousseau: The Confessions of Jean Jacques Rousseau, transl. Samuel William Orson, Book VI, Project Gutenberg

Original text:

|

But let's get back to the poolish. Suppose this method really was developed to economise on mass-produced pressed yeast. It's hard to figure out, then, how it could have been done about a hundred years before such yeast actually hit the market. I suggest we no longer bother our heads about a headless queen and look for more reliable sources instead. Let's see, for example, what Bakerpedia, an online baking encyclopedia, has to say about the origin of poolish:

| This breadmaking method was first developed in Poland during the 1840s by a nobleman named Baron Zang. Poolish was later spread by Viennese bakers into Austria who upon emigrating to France around 1840 initiated the production of Vienna breads and other luxury bakery products in Paris using the Poolish technique. With this technique bakers switched from using associations of yeast and sourdough […] to yeast alone for carrying out fermentation at the bakeshop. |

| — Poolish, in: Bakerpedia |

So it wasn't an Austrian princess who helped introduce poolish to France when she arrived there in 1770; it was a nobleman who came to France from Austria 70 years later! But the crucial bit that both sources agree on is that poolish is a Polish invention. That's hardly surprising, as Poland is famous for its bread. It's more famous for its rye sourdough loaves than for yeast-raised wheat baguettes, though, but we wouldn't want to question this great Polish achievement and yet another source of Polish national pride, would we?

Of course we would! And so, by tracing the ultimate source of the information that eventually found its way to Bakerpedia and many other texts (print and online), we can determine that it relies on the authority of Raymond Calvel, the professor of baking at the National Higher School of Milling and Cereal Industries (ENSMIC) in Paris who wrote the book on baking bread. This is what the book, The Taste of Bread, says about where the poolish method comes from:

| This method of breadmaking was first developed in Poland during the 1840s, from whence its name. It was then used in Vienna by Viennese bakers, and it was during this same period that it became known in France. The bread produced by this method became known as Vienna bread, named for those Austrian bakers who began to make it in Paris after having come from Vienna. The poolish method seems to have become the only breadmaking method used in France until the 1920s for production of breads leavened solely with yeast. […] The Vienna bread made during that period was the result of a production method introduced into France by an Austrian, Baron Zang. With the assistance of a group of Viennese bakers, the Baron began to produce this type of bread in Paris in 1840, in a bakery that still exists today on the Rue de Richelieu. This bread corresponded to our definition of “traditional” bread, since it was made from a mixture of flour, water, yeast and salt, occasionally enriched with the addition of a little malt extract. It was leavened with a poolish, and was thus a baker's yeast leavened product. During the whole of the 1840s–1920s, this type of bread experienced well-deserved commercial success in the larger French cities, especially Paris. As may be seen still today on the advertising signs of old bakeries, the consumer had the choice between “French bread” made from levain [i.e., sourdough starter], and Vienna-style bread, made from baker's yeast. | ||||||

— Raymond Calvel: The Taste of Bread, transl. Ronald L. Wirtz, ed. James J. MacGuire, Springer Science+Business Media, 2001, p. 42, 116

Original text:

|

If a breadmaking expert of this stature said that poolish was of Polish origin, the hardly anyone saw the reason to question this assertion. Well, alright, but who was this supposedly Polish baron with a rather non-Polish-sounding name, credited with bringing from Austria to France the pre-ferment which gave rise to French baguettes?

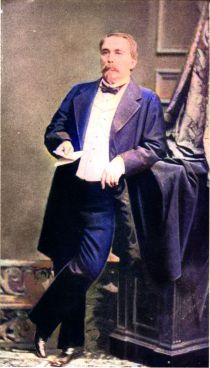

The Baker in Spite of Himself

According to Jim Chevalier, a specialist in French bread history, Christopher August Zang was born in 1807 in the family of a Viennese surgeon. As a young man, Zang served as an artillery officer and studied chemical engineering in the Austrian capital. When he was 28, his military career was cut short by his father's death. After all, why pursue a career of any kind, if you've inherited a fortune from your dad? The inheritance was enough for some time of carefree indulgence and then, all of a sudden, it ran dry. Zang managed a soft landing by marrying into an affluent family, but this experience taught him that once you earn some funds, it's better to invest them rather than blow them all on consumption. And so Zang discovered in himself a knack for entrepreneurship.

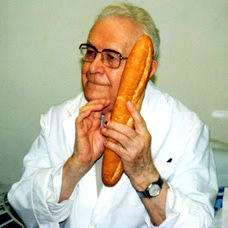

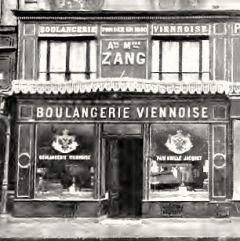

As a keen observer, Zang noticed visiting French people raving about Viennese bread. Whenever he was in Paris, he could see for himself that French bread – dark, heavy and sour – was nothing like what was available back in Vienna. There was an obvious niche on the French baking market and Zang resolved to enter this niche with a little capital. In 1837 he moved to Paris, where he and his business partner, Ernest Schwarzer, opened a new bakery at 92, rue de Richelieu. Do you need to know anything about baking bread to run a successful bakery? Not necessarily, as Zang and Schwarzer promptly demonstrated; all you need is to hire good Viennese bakers, trust that they know what they're doing and have the guts to invest in the technological innovations these bakers recommend. In the meantime, the owners focused on marketing; after all, if you're investing in technological novelties, your customers should be made aware of that. And so, Zang's patrons (Schwarzer sold his share to Zang in 1839) soon learned that the dough for Zang's bread is kneaded not by a sweaty half-naked baker, but by a modern, hygienic machine, and that the loaves are baked in a special steam oven which give the finished product an appetisingly shiny crust. Parisians were quick to learn about the advantages of "Viennese" baked goods, which owed their highly-prised aroma, lightness, whiteness and freshness to a combination of good Hungarian wheat flour and baker's yeast (free from the hoppy bitterness of brewer's yeast).

Zang's establishment was known as Boulangerie Viennoise, or "Viennese Bakery". True to its name, it offered Austrian breadstuffs that had been hitherto unknown in Paris, such as Kipferl, or Viennese crescent rolls (dubbed "croissants" by the French), and Kaisersemmel, or kaiser rolls (which Parisians referred to simply as "petits pains viennois", or "little Viennese breads"). Zang's commercial success was quickly copied by local bakers, so that by 1840 there had already been a dozen shops offering "Viennese" breads in Paris.

Eight years later a wave of revolutions known as the Springtime of Nations swept across Europe, upsetting the order which had been established in the wake of Napoleonic wars. France became a republic again; political reforms Austria brought about a greater freedom of the press. For Zang this was an occasion to invest in a completely new business. He sold his Parisian bakery and returned to Vienna, where he became a newspaper publisher. Here, again, he invested in innovation: his paper Die Presse published short paragraphs arranged in columns, novels in episodes and numerous advertisements which helped maintain a competitive price. Zang stayed in this business for two decades until he sold his publishing house only to move on to banking and mining (the lignite mine that he purchased in Styria bears the name Zangtal to this day).

Zang był niewątpliwie człowiekiem zamożnym i wpływowym, ale baronem był tylko w sensie metaforycznym, bo żadnych tytułów szlacheckich ani nie odziedziczył, ani nie zdobył za życia. Czy był dumny ze swojego wkładu w rozwój francuskiego piekarstwa? Niespecjalnie. Ten epizod w swoim życiu starał się raczej ukryć, tym bardziej, im częściej przeciwnicy biznesowi i polityczni nazywali go zwykłym piekarzem. Na przekór tym staraniom jego nazwisko pozostało na tyle silną marką na paryskim rynku pieczywa, że kolejni właściciele piekarni przy ul. Richelieu 92 za żadne pieniądze nie chcieli się zgodzić na usunięcie słowa „Zang” z szyldu – jeszcze długo po jego śmierci w 1888 r.

Tymczasem pieczywo wiedeńskie we Francji ewoluowało. Na początku XX w. przyjęło się w języku francuskim słowo „viennoiserie” (czyt.: „wienłaz-ri”) na oznaczenie „luksusowego pieczywa typu wiedeńskiego”, ale równocześnie owa „wiedeńszczyzna” stawała się coraz bardziej francuska niż wiedeńska. Do wyrobu rzekomo wiedeńskich rogalików zaczęto używać ciasta francuskiego zamiast tradycyjnego ciasta drożdżowego. To ostatnie przetrwało jednak w bułkach nowego typu, który upowszechnił się dopiero w latach 20. Były to bułki długie i wąskie, białe i słodkawe (co odpowiadało konsumentom), ale błyskawicznie czerstwiały, więc trzeba było je kupować nawet 2–3 razy dziennie (co odpowiadało właścicielom piekarni). Od charakterystycznego kształtu nazwano je „pałeczkami”, czyli „bagietkami” („baguettes”). I tak narodziło się francuskie pieczywo, jakie znamy dzisiaj. W tym czasie poolish był już we Francji w użyciu, zwłaszcza przy wyrobie bagietek właśnie. Ale było to już długo po śmierci Zanga, a jeszcze dłużej po tym, jak sprzedał swoją paryską piekranię. A to znaczy, że upowszechnienie tej metody we Francji to raczej nie jego zasługa.

TL;DR: To prawda, że Zang założył w Paryżu piekarnię, w której zatrudnił sprowadzonych z Wiednia piekarzy, ale sam nie był ani piekarzem, ani baronem, ani Polakiem, i to nie to nie on sprowadził do Francji poolish. A jeśli nie on, to kto? I czy mogli to być jacyś Polacy?

What's in a Name?

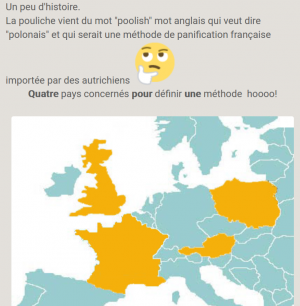

| “Poolish” comes from an English word which means “Polish” and refers to a French breadmaking method imported by the Austrians. Four countries to define one method! | ||||

— Marc Dewalque: La pouliche ou poolish, histoire, in: BoulangerieNet, 3 October 2007, own translation

Original text:

|

Wiemy już, że Calvel, choć wielkim autorytetem w dziedzinie pieczenia chleba był, to jednak nie był nieomylny, zwłaszcza w kwestiach historycznych. Zresztą wygląda na to, że historię o „baronie” Zangu „z Polski” powtórzył po kimś innym, bo ta sama informacja pojawiła się już w 1972 r. w amerykańskim miesięczniku The Atlantic Monthly.[1] Czy jest zatem możliwe, że mylił się nie tylko co do polskiego pochodzenia Zanga, ale też co do polskiego pochodzenia metody poolish? Przyglądnijmy się samemu słowu: pisownia nie wygląda ani na polską, ani na niemiecką, ani na francuską. Jeśli w ogóle na jakąś wygląda, to najprędzej na angielską – ale jakąś dziwną, coś jak „Polish”, czyli „polski”, ale nie wiadomo dlaczego przez dwa „o”.

W poszukiwaniu etymologii słowa „poolish” przebadałem przeróżne starożytne źródła, od notowań z giełd zbożowych z XIX w. aż po fora internetowe dla piekarzy z początków XXI w. Wychodzi na to, że hipotez jest kilka, ale żadna nie jest do końca przekonująca.

Poolish ← Polish

Najbardziej rozpowszechnione (drogą bezkrytycznego powtarzania) jest powiązanie słowa „poolish” z angielskim przymiotnikiem „Polish”. Niektóre źródła podają, że „Poolish” to dawna alternatywna pisownia tegoż przymiotnika, ale nie udało mi się znaleźć słownika, który by to potwierdzał. Lecz gdyby nawet tak było, to takie wyjaśnienie więcej gmatwa niż wyjaśnia: dlaczegóż polską metodę sprowadzoną z Austrii mieliby Francuzi nazywać archaicznym angielskim słowem? Frustrację bezsensownością tej propozycji najlepiej chyba wyraża ten wpis pana Thierrego Martina, jednego z użytkowników francuskojęzycznego forum BoulangerieNet:

| But the word itself? Why the heck an English one? And an old English one at that? And only used in France, as it's used neither in Poland nor in Austria, nor in England! | ||||

— Thierry Martin: La poolish est-elle polonaise ?, in: BoulangerieNet, 21 February 2010, own translation

Original text:

|

Trochę dalej ten sam użytkownik (dentysta i piekarz-amator z wyspy Reunion) dochodzi do słusznego wniosku, że choć Polacy słyną z tego, że świetnie znają się na pieczeniu chleba, to to jednak za mało, żeby dowieść polskiego pochodzenia metody poolish.

Poolish ← Polnisch

Niektóre z najstarszych francuskich wzmianek o tym niby-polskim zaczynie używają pisowni „poolisch” lub „polisch” (przez „sch”), co podpowiada alternatywną wersję powyższej etymologii, a mianowicie, że to słowo pochodzi nie z angielskiego, lecz z niemieckiego. Ale czy „polski” po niemiecku nie pisze się przez „n”, czyli „polnisch”? W dzisiejszej standardowej niemczyźnie – owszem, ale jeszcze w XIX w., zwłaszcza w odmianach południowych, używanych m.in. w Austrii, to samo słowo pisało się też w różnych wariantach bez „n”, jak: „polisch”, „pohlisch” czy „pollisch”. A niektóre z nich pojawiały się również w kontekście zaczynu na chleb. Na przykład w reklamie prasowanych drożdży wiedeńskiej marki St. Marxer z 1865 r. jest mowa o metodzie „Polisch”. Z czasem to słowo, w tym znaczeniu, zdało się ulec w niemczyźnie zapomnieniu, choć jeszcze w późniejszej o sto lat niemieckiej publikacji o pieczeniu chleba można znaleźć informację o cieście na chleb typu „polische”:

| Wyrób ciasta typu polische, wymagający minimalnej ilości drożdży, był […] w tamtym czasie standardową metodą produkcji jasnego pieczywa wiedeńskiego. Zastosowanie tak czasochłonnego procesu było możliwe dzięki temu, że w epoce pracy ręcznej czas pracy był praktycznie nieograniczony. Był to wybór mniejszego zła: lepiej było, wyrabiając polische, zgodzić się na nieco szorstki, łatwo kruszący się i bledszy w kolorze wypiek niż jeszcze bardziej obniżyć jakość pieczywa poprzez użycie większej ilości drożdży piwnych. | ||||

— Brot und Gebäck, vol. 19–21, Arbeitsgemeinschaft Getreideforschung, 1965, p. 151, tłum. własne

Original text:

|

Ale to nadal nie jest jednoznaczny dowód na to, że ową metodę opracowano w Polsce. Dr Matthew Baerman, w artykule dla językoznawczego bloga Morph, sugeruje, że skojarzenie niemal płynnej podmłody z Polską ma związek z polskim żurkiem (mimo że tego ostatniego wcale nie robi się na drożdżach).[2] Tym bardziej, że w niektórych źródłach niemieckich luźna podmłoda bywa nazywana wprost „polnische Suppe”, czyli „polską zupą”.[3] Nota bene, o czym dr Baerman mógł nie wiedzieć, słowo „żurek” w polskiej terminologii piekarskiej oznacza rodzaj wstępnego zakwasu (czyli półkwasu) o płynnej konsystencji. Ale takiego żurku używa się do wyrobu chlebów z mąki żytniej na zakwasie, a nie do drożdżowego pieczywa pszennego. Istnieją wprawdzie pieczywa mieszane, pszenno-żytnie, do których używa się zarówno żurku, jak i podmłody, ale nawet wtedy żurek przygotowuje się osobno z mąki żytniej, a podmłodę – osobno z mąki pszennej.[4][5]

W każdym razie, jak przyznaje sam dr Baerman, sugestia, że słowo „poolish” nawiązuje do polskości żurku, ma jedną zasadniczą wadę: brak na nią żadnego potwierdzenia w źródłach.

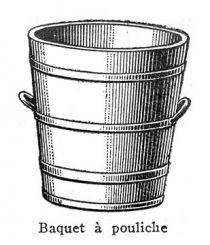

Poolish ← Pouliche

Ale to nie koniec komplikacji. W najstarszych tekstach o poolish pojawia się zupełnie inna, znacznie bardziej francuska, pisownia: „pouliche”. I to nie tylko w źródłach francuskojęzycznych; „pouliche” pojawia się np. w artykule o paryskich piekarniach, który ukazał się w amerykańskim czasopiśmie młynarskim z 1897 r.,[6] a także w amerykańskim podręczniku napisanym przez austriackiego piekarza w 1903 r.[7]

Sęk w tym, że słowo „pouliche” (czyt.: „pu-lisz”) ma w języku francuskim znaczenie zupełnie niezwiązane z piekarstwem, oznacza bowiem… klaczkę! Tylko co ma wspólnego młoda samica konia z zaczynem drożdżowym? Być może podmłoda, mająca przecież odmłodzić populację drożdży, skojarzyła się komuś z młodym ssakiem? Może fermentujące ciasto przywiodło komuś na myśl rozbrykaną klaczkę? Możemy tylko się domyślać. W każdym razie wspomniany już Jim Chevallier przychyla się ku tej właśnie etymologii. Jego zdaniem niby-angielska pisownia fonetyczna „poolish” pojawiła się później i dopiero wtedy, przez skojarzenie „poolish – Polish”, dorobiono do niej historyjkę o polskim pochodzeniu metody. A żeby tę historyjkę uwiarygodnić oraz wytłumaczyć, jakim sposobem ta rzekomo polska metoda dotarła do Francji, wyszukano jeszcze brakujące austriackie ogniwo w osobie słynnego Augusta Zanga.

Poolish ← פאליש

Znalazłem też jeszcze bardziej zaskakującą hipotezę, według której słowo „poolish” pochodzi od słowa „polisz” (פאליש), które w języku jidysz oznacza przedsionek synagogi. Hipoteza opiera się na skojarzeniu, że podmłoda jest pierwszym krokiem do uzyskania gotowego wypieku, czyli swego rodzaju przedsionkiem, takim jak polisz w bożnicy. W dialekcie środkowym (polsko-galicyjskim) języka jidysz samogłoska „o” jest bardziej zbliżona do „u”, co tłumaczyłoby pisownię przez „oo” w transkrypcji angielskiej, a zarazem znowu łączyłoby pochodzenie pomysłu na zaczyn z Polską. Tylko że tym razem autorstwo tej metody należałoby nie do Polaków w ogóle, a do polskich Żydów.

Prof. David Gold, który zaproponował to wyjaśnienie, sam przyznaje, że jest mocno naciągane.[8]

Or Maybe It's Poolish ← Polish After All?

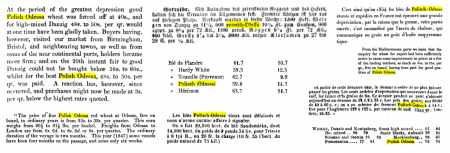

Szukając możliwie najstarszych punktów zaczepienia, odkryłem, że w zachodnioeuropejskiej prasie z pierwszej połowy XIX w. wielokrotnie pojawiało się zestawienie słów „Polish Odessa” (pisane też „Polisch Odessa”) – o tyle zaskakujące, że Odessa nigdy nie była polskim miastem. Okazuje się jednak, że tak właśnie nazywano pszenicę importowaną z obszaru, który dziś nazwalibyśmy zachodnią Ukrainą.

Oto jak polskie odmiany pszenicy scharakteryzowano we francuskiej książce o handlu zbożem z 1910 r.:

| Pszenica z Polski jest eksportowana przez Gdańsk i Odessę; często bywa mylona z pszenicą rosyjską i nazywana jest „pszenicą z Odessy”, jeśli jest eksportowana przez ten właśnie port. Są to odmiany białe, żółte i czerwone; najwyżej cenione, zarówno czyste, jak i zmieszane, są te spod Sandomierza i Krakowa. […]

Do najczęściej stosowanych odmian [pszenicy importowanej z Rosji] należy [m.in.] pszenica Polish, czerwona, wysokiej jakości. Nazywana jest „nerwową”, co znaczy, że sprzyja wyrastaniu ciasta […] | ||||

— Paul van Hissenhoven: Les grains et le marché d'Anvers, Anvers: Imprimerie Aug. van Nylen, 1910, p. 24, tłum. własne

Original text:

|

W XIX w. pszenicę, która wyrosła na ziemiach dawnej Rzeczypospolitej pod zaborem rosyjskim, eksportowano dwoma drogami: północną, czyli z południowej Kongresówki (okolice Sandomierza), najpierw Wisłą przez zabór pruski do Gdańska, a stamtąd na holenderskich statkach przez Bałtyk i Morze Północne do Londynu; oraz południową, czyli z Wołynia i Podola, Dniestrem do Odessy, a dalej na greckich statkach przez morza Czarne i Śródziemne, i wreszcie też do Londynu. Londyn był wtedy głównym ośrodkiem handlu zbożem w Europie; to na londyńskich giełdach spekulowano ziarnem, zanim jeszcze dotarło do Anglii, ustalano jego ceny oraz decydowano, do których portów w zachodniej Europie ostatecznie trafią poszczególne partie pszenicy.[9]

A zatem nie powinno dziwić, że również we Francji pszenica z Polski była znana pod angielską marką „Polish”. To wynikało po prostu z roli Londynu w międzynarodowym handlu zbożem. Przy czym Francuzi zawsze byli dość kreatywni w masakrowaniu słów, które zapożyczali z angielskiego (dość przypomnieć, że „szampon” po francusku to „shampooing”, a „radiotelefon” to „talkie-walkie”), więc fakt, iż angielskie słowo „Polish” zdarzało im się pisać: „Polisch” czy nawet „Poolish”, też nie powinien zaskakiwać.

A teraz pora na moją własną hipotezę: otóż metoda poolish została wymyślona we Francji, a jej nazwa wzięła się stąd, że najlepsze efekty dawała przy użyciu mąki z „nerwowej” polskiej pszenicy, którą znano we Francji pod angielskim określeniem „Polish”, przekręconym przez Francuzów na „Poolish”. Dopiero kiedy ta nazwa się przyjęła, z wymową „pulisz” zgodną z owym niby-angielskim zapisem, utworzono fonetyczną francuską pisownię „pouliche”, która przypadkiem oznacza również klaczkę.

Czy ta propozycja ma jakieś poparcie w źródłach? Żadnego. Czy jest naciągana? Zdecydowanie. Ale czy jest bardziej naciągana niż te przedstawione wyżej? To już zostawię ocenie Czytelników. A więc co wiemy na pewno? Tyle, że poolish wynaleziono raczej we Francji, a nie w Polsce, i dopiero w drugiej połowie XIX w., więc nie mógł jej spopularyzować ani August Zang, ani – tym bardziej – piekarze z dworu Marii Antoniny. Ale pochodzenie nazwy tej metody pozostanie nadal zagadką.

References

- ↑ Betty Suyker: A la Recherche du Pain Perdu, in: The Atlantic Monthly, Boston: lipiec 1972, p. 90–92; cyt. w: Matthew Baerman: Poolish, in: Morph: A Blog About Languages And How They Change, 24 kwietnia 2019; a także cyt. w: Mae Travels: Baker's Words, in: Mae's Food Blog, 14 lutego 2018

- ↑ Matthew Baerman: Poolish, in: Morph: A blog about languages and how they change, 24 kwietnia 2019

- ↑ Martin Seiffert: Technik der Weizenvor- und Sauerteig-Führungen in Deutschland und Europa, in: Handbuch Sauerteig, red. Markus J. Brandt, Michael Gänzle, Behr's Verlag, 2006, p. 286

- ↑ Piekarstwo: receptury, normy, porady i przepisy prawne, red. Mieczysława Janik, Warszawa: Zakład Badawczy Przemysłu Piekarskiego, Handlowo-Usługowa Spółdzielnia „Samopomoc Chłopska”, 2002, p. 11–12

- ↑ Technologia żywności: podręcznik dla technikum, red. Mieczysław Dłużewski, cz. 4, Warszawa: Wydawnictwa Szkolne i Pedagogiczne, 2008, p. 23

- ↑ W.S. Harwood: The Bread of Paris, in: The Northwestern Miller, v. 44, Minneapolis: Miller Publishing Company, październik–grudzień 1897, p. 31

- ↑ Emil Braun: Baker's Book: A Practical Hand Book of All the Baking Industries in All Countries, vol. 2, New York: Van Nostrand, 1903, p. 317; cyt. w: Jim Chevallier: Before the Baguette: The History of French Bread, North Hollywood: Chez Jim, 2019

- ↑ David L. Gold: Studies in Etymology and Etiology: With Emphasis on Germanic, Jewish, Romance and Slavic Languages, Universidad de Alicante, 2009, p. 584–585

- ↑ Morton Rothstein: Centralizing Firms and Spreading Markets: The World of International Grain Traders, 1846–1914, in: Business and Economic History, Second Series, vol. 17, Business History Conference, 1988, p. 103–113

Bibliography

- Raymond Calvel: Le Goût du Pain : Comment le préserver, comment le retrouver, Éditions Jérôme Villette, 1990

- Jim Chevallier: August Zang and the French Croissant: How Viennoiserie Came to France, North Hollywood: Chez Jim, 2009

- Jim Chevallier: Before the Baguette: The History of French Bread, North Hollywood: Chez Jim, 2019

- Henryk Piesiewicz: Podmłody – ważny element procesu produkcji, in: Przegląd Piekarski i Cukierniczy, Warszawa: Wydawnictwo Czasopism i Książek Technicznych SIGMA-NOT, maj 2013, p. 28–30

- Henryk Piesiewicz: Powrót do tradycyjnych rozczynów: Podmłody, in: Przegląd Piekarski i Cukierniczy, Warszawa: Wydawnictwo Czasopism i Książek Technicznych SIGMA-NOT, grudzień 2013, p. 20–22

| ◀️ Previous | 📜 List of posts | Next ▶️ |

| ⏮️ First | 🎲 Random post | Latest ⏭️ |