What Has the Battle of Vienna Given Us?

12 September this year was the 335th anniversary of the Relief of Vienna – the time when once again a wave of savages from the east crashed against the Polish breakwater protecting European civilization from its doom. And also the moment which saw (or heard) the famed Polish Winged Hussars’ swansong. Or so, at least, I’ve been taught at school.

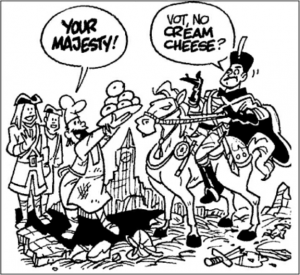

Okay, but this blog is not about geopolitical or military myths; it’s about culinary myths. So let’s see how the Victory of Vienna helped enrich our menus. Well, if we judge the importance of a historical event by the number of culinary myths associated with it, then the Battle of Vienna was certainly a momentous one indeed. And should all these legends be true, then whether you’re having borscht with potatoes in Poland or Ukraine, washing down you breakfast croissant with coffee in Vienna or spreading your bagel with cream cheese in New York, you should be grateful to King John III Sobieski for his spectacular victory over the Ottoman Turks.

Potatoes

| The fact that John III brought the potato to [his royal palace at] Wilanów from the Viennese expedition is considered incontestable in the subject-matter literature. A sceptic, who remembers [Sobieski’s] retreat from Párkány [a follow-up battle to the siege of Vienna] from his history classes, might think that King John had more pressing problems on his head following his famous victory, but the king’s letter, which has assertedly been preserved, testifies to the contrary. | ||||

— Piotr Zalewski: Ziemniak jako roślina uprawna – fragmenty historii, in: Inżynieria Rolnicza, 5 (114), 2009, p. 311–318, own translation

Original text:

|

The fact is, as we can see, assertedly incontestable. So, assertedly, John III got a bag of potatoes from Emperor Leopold I in return for saving Vienna from the Turks. Because, you know, everybody knows the Poles love their spuds, so the Polish king must have been happy, right? Except that the Poles back then not only didn’t love potatoes yet, they had absolutely no idea what they were. We don’t know whether John was happy to receive such a magnificent gift, but we do know that he (assertedly) sent the taties to his wife, asking her to have them planted in their yard.

The man who actually planted them was the Wilanów gardener Paweł Wienczarek, who later transferred his potato-planting knowledge to his son-in-law, Jan Łuba. The latter is known for being the first in Poland (during the reign of the next king, Augustus II) to grow potatoes on a larger scale in his garden at Nowolipki near Warsaw and sell them as a luxury item to the royal and magnate kitchens. At least this is what Orgelbrand’s 1868 encyclopedia says. Prof. Zalewski, already quoted above, adds that Łuba imported whole wagons of seed potatoes from Saxony, as the king “demanded a platter of potatoes (fried whole) with his every dinner”, citing (wait for it) “a well-informed historian”.

Jędrzej Kitowicz, an 18th-century priest known for his account of everyday life in Poland during the reign of Augustus III, also pointed to Saxony as the place where the “earth apples” were imported from. Potatoes were not an immediate hit, according to him. Some priests, he wrote, spread around the opinion that these tubers were disgusting in taste and unhealthy. And the reason they were doing this was that they were afraid that someone might inadvertently commit sacrilege by mistakenly adding potato starch instead of wheat flour to the dough for altar bread.[1]

But let’s go back to Sobieski. The truth is, even if he had received a bag of potatoes from the emperor as a present, it’s still unlikely that he ever developed a taste for them. In those times rich people (and they were the only ones who could afford potatoes) found the idea of eating something that grows or lives in dirt repulsive. They treated the potato as a botanical curiosity and had it grown as a decorative plant, but were completely uninterested in the dirty, unshapely tubers. There was an exception to their distaste for things found in earth, though: truffles. There must have been a clever potato dealer who persuaded his customers that the potato is kinda like a truffle, as the German word for “potato”(borrowed into some dialects of Polish as well) is Kartoffel, which comes from tartufo, the Italian word for “truffle”. It took about a hundred more years before potatoes got cheap enough that the peasants could discover the advantages of this versatile vegetable, which you can not only cook and eat in so many ways, but also use to make starch, fodder and, of course, vodka.

Beets

Another vegetable, which seems indispensable to traditional Polish peasant cookery, but which actually appeared in Poland relatively late, is the beetroot. Beets were grown in the Mediterranean Basin already in antiquity, but more for their leaves than for their roots – which at the time were whitish, long, tapered, bitter and considered inedible. The beet variety with a dark red, round and sweet taproot did not appear in southern Europe before the 12th century and it only reached Poland in the 16th. Ukrainians may have discovered it even later:

| According to one legend, Zaporizhian Cossacks have a direct link with the invention of borscht. In 1683, armies of the Ottoman Empire besieged Vienna. Armies of Christian nations, led by King John Sobieski of Poland, rushed to the Austrians’ rescue. Among coalition soldiers there were also Ukrainian Cossacks. Time was scarce, the two-thousand-strong Turkish army was pressing on Vienna and the Austrian capital may have fallen at any time. The Cossacks were in such haste to help their allies that they failed to gather adequate provisions. They had to eat whatever they could find in local gardens. But the Cossack soul – and the Cossack stomach in particular – needed something tasty and filling. Fortunately, the Cossacks had pork fatback – yet another culinary symbol of Ukraine. And then it occurred to someone to sauté beetroots in lard before cooking them in stock. The result was both quick and tasty, especially considering the conditions in which the Cossacks had found themselves. This is how the procedure of sautéing was invented, which allows the beetroots to retain their colour and taste. On top of that, the Polish-Austrian armies defeated the Turks so overwhelmingly that the Turkish pasha sentenced his favourite vizier to death. | ||||

— Andrey Khoroshevsky: 100 znamenitykh simvolov Ukrainy [100 знаменитых символов Украины], Kharkov: 2007, p. 83, p. 83, own translation

Original text:

|

Which means that if not for John III’s relief of Vienna, Ukrainians would not have come up with the idea to cook their borscht with beetroots instead of hogweed (which was the original ingredient; in fact, the very word “borscht” comes from the Slavic name for hogweed). Which is great, only that, according to Nikolai Burlakoff,[2] there is another version of this legend as well. It turns out, as in Radio Yerevan news, that it wasn’t the Zaporizhian Cossacks, but the Don Cossacks; that they didn’t serve in the Polish army, but in the Russian army; they weren’t marching towards Vienna, but towards Azov; and that they weren’t going to save it from being captured, but to capture it (which happened in 1695).

Whatever the case, more reliable information about beetroot-based borscht does not appear before the 19th century. But who knows? Perhaps the Cossacks did add sautéed beetroots to their borscht as early as the late 17th century?

Croissants

One blogger, who signs his posts as “bfaure”, displays quite a healthy approach to this kind of legends. This is how he prefaces another one of them:

| So, one starts the homage to the magnificent croissant with a story of its origin too good to be true – which of course it isn’t. When it comes to food, however, great stories don’t have to be true in order to be truly great, and this one has all the elements of greatness. |

| — bfaure: The Magnificent Croissant and Jan III Sobieski, in: Rampants of Civilization, 2016 |

According to this legend, while the Cossacks were picking beetroots on their way to Vienna, the city itself, two months into a siege, was starting to face starvation – a common trope in culinary myths. Nevertheless, bakers continued to work their night shifts to provide the inhabitants with their daily bread. One of them (said to come from the German city of Münster) happened to hear some weird noises from underground. As it turned out, he discovered a tunnel which the Ottomans had dug under the city walls. In recognition of this contribution to the war effort, the emperor awarded Viennese bakers the right to bake rolls in the shape of the Turkish crescent. Thus the kipferl, or the Viennese croissant, was born. Although, if we were to believe Larousse Gastronomique, the bible of French gastronomy (I will be coming back to this tome, as it’s a wonderful source of culinary myths presented as facts), the croissant was actually created three years later to celebrate the capture of the Ottoman city of Buda (or what is now Budapest) by Christian forces.

Bagels

This legend has its Jewish variant as well, which says that Viennese Jews, in gratitude to the Polish king and his Winged Hussars, baked special rolls in the shape of a stirrup. And as the German word for “stirrup” is Bügel, the rolls have been dubbed “bagels”. The bagels would later travel all the way to New York, where a sandwich of a halved bagel spread with cream cheese and covered with a slice of lox (smoked salmon) became the favourite snack, first among American Jews, and in the second half of the 20th century – among Americans in general.

Of course, you can always count on Americans to try and cross-breed two good things to get something supposedly even better. This is how one Brooklyn bakery in 2014 created the cragel, or a croissant and bagel in one.

The legend fails to explain one thing: why would the Viennese Jews need to invent the bagel, if Cracovian Jews had been already baking it for years? The oldest known mention of the Jewish bagel comes for sumptuary laws issued by the Jewish community of Cracow in 1610. Mentions of the obwarzanek🔊, a Polish ring-shaped bread closely related to the bagel, date back even further, to the early 15th century (I promise to write how to tell a bagel from an obwarzanek and an obwarzanek from a pretzel in a separate post). But according to Maria Balinska,[3] the association between King John III and the bagel is not entirely unfounded, if not as romantic as the legend would have it. As it happens, the saviour of Vienna was the first king of Poland who did not confirm a privilege, first issued by King John Albert in 1496, which gave the Cracovian guild of bakers (Christian only) a monopoly for baking wheat-flour bread and obwarzanki. What it meant is that Jewish bakers could finally bake their bagels legally and sell them openly to both Jewish and Christian customers. No wonder the Yiddish phrase in meylekh Sabetskis yorn (literally, “in King Sobieski’s time”) is synonymous to “good old days”.

Coffee

Let’s return to the croissants for a while.

| Of course, that [is] not how the croissant originated. It would be an additional two hundred years before anybody would determine a recipë for the fantastic pastry we recognize today. No matter. The glory of the croissant resonates with us, even if the story told is a wonderful myth. Me? I like my myths, with coffee, thanks. |

| — bfaure, op. cit. |

That’s right, what better to wash down you croissants, bagels and myths with, if not coffee? And if we’re talking about coffee, then we cannot forget Georg Franz Kolschitzky (or Jerzy Franciszek Kulczycki in Polish) who served the Christian coalition forces as a spy and interpreter. If you’re not interested in biographical details, please skip the next paragraph.

| According the contemporary sources, Kulczycki considered himself a “native Pole” coming from the “Polish royal free city of Sambor”. He probably belonged to a Polonized, Roman Catholic branch of a Ukrainian family, which belonged to the noble clan Lis and originated from the village of Kulchytsi near Sambir [in what is now western Ukraine]. Nevertheless, Kulczycki’s ethnicity has often been a bone of contention. Ukrainian scholars consider him an Orthodox Ukrainian from Zaporizhia, who fought many times against the Turks and spent two years in captivity. Austrian and Hungarian historians claim he was a Serb named Đura Kolčić of Sombor with a fake Polish identity. Nothing is known about Kulczycki’s youth except that the arrived in Vienna from Serbia. He spoke both Turkish and Hungarian, which landed him a job as an interpreter at the Oriental Company, a society of Viennese merchants trading with the Ottoman Empire. Having become an independent merchant of oriental commodities, he settled at Leopoldstadt near Vienna. In July of 1683, during the siege of the imperial capital, after five weeks of hostilities, he dressed up as a Turkish soldier and – with the consent of the mayor and the commander of the city’s defences, Count Starhemberg – he left the city in the evening of 13 August to get help. He passed through the Turkish camp without problems and in the morning of 15 August he reached Duke Charles V of Lorraine, with whose written response he returned to Vienna. This feat brought him fame and riches; he was awarded Viennese citizenship and a plot of land for his new house. | ||||

— Hanna Widacka: Jerzy Franciszek Kulczycki – założyciel pierwszej kawiarni w Wiedniu, in: Silva Rerum, Muzeum Pałacu Króla Jana III w Wilanowie, own translation

Original text:

|

The legend about Koltschitzky says that, as well as the prizes mentioned above, the king of Poland gifted him some of the goods looted in the Ottoman camp, including bags of something that has been originally taken for camel fodder. Familiar with Turkish customs, Koltschitzky immediately recognized the contents of these bags as coffee beans. So equipped, he opened the first café in Vienna, called Hof zur Blauen Flasche, or the Blue Bottle House. For marketing reasons, he served his patrons in Turkish garb – perhaps the same as the one he had used to carry messages between the besieged Vienna and the camp of the allied forces. He is also credited with the idea of making coffee more palatable to Christians, unaccustomed to the bitter brew, by adding a splash of milk and honey.

But even to this legend there is a counterlegend, according to which Koltschitzky did not open the first coffeehouse in Vienna, because he had been beaten to it by three years, by an Armenian (or maybe Greek?) merchant named Johannes Diodato. That said, Koltschitzky was without a doubt one of two Poles – alongside Franciszek Trześniewski🔊, creator of Vienna’s “unpronounceably good” open sandwiches – who made great contributions to Vienna’s culinary scene. Unless Koltschitzky was Ukrainian, that is. Or Serbian.

That’s all for today, but do let me know in the comments section what you would like to read more about. Is it borscht, bagels or coffee? So long!

References

- ↑ Jędrzej Kitowicz: O Kartoflach, in: Opis obyczajów i zwyczajów za panowania Augusta III, Poznań: Edward Raczyński, 1840, p. 111

- ↑ Nikolai Burlakoff: The World of Russian Borsch, North Charleston, SC: Createspace Independent Pub., 2013

- ↑ Maria Balinska: The Bagel: The Surprising History of a Modest Bread, Yale University Press, 2008

| ◀️ Previous | 📜 List of posts | Next ▶️ |

| ⏮️ First | 🎲 Random post | Latest ⏭️ |