Difference between revisions of "A Menu Lost in Translation"

| (129 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | {{data|1 April | + | {{data|1 April 2022}} |

| − | On this first day of April, | + | On this first day of April, I’d like to propose a special dinner menu composed entirely of authentic Polish specialities. All of these dishes have been gleaned from actual English-language menus of various restaurants across Poland. Enjoy! |

| − | {| style=" | + | {| style="margin: auto; width: 50%;" |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | [[File:Menu z translatora.png|class=full-page|]] | + | | [[File:{{#setmainimage:Menu z translatora.png}}|class=full-page|]] |

|} | |} | ||

| − | Oops, it looks like someone used a machine translator to render the Polish menu into English | + | Oops, it looks like someone used a machine translator to render the Polish menu into English! |

| − | + | Believe it or not, even some relatively upscale restaurants do this without even having the menu proof-read by someone who actually speaks English. The results are sometimes hilarious, sometimes just confusing, and some are downright off-putting to any visiting foreign tourist. But I kid you not: all of the items in the menu above are inspired by real-life mistranslations which found their way into actual bills of fare. | |

| − | + | So, have you figured out what they were supposed to mean? You can type your guesses as comments to [https://m.facebook.com/story.php?story_fbid=942768843077973&id=228322137855984&m_entstream_source=timeline&paipv=1 this Facebook post.] Unless you speak Polish, then you don’t need to guess; but in that case, please don’t spoil the fun! | |

| − | {| class="mw-collapsible mw-collapsed" data-expandtext="Show actual meanings" data-collapsetext="Hide actual meanings" | + | <nomobile>And if you’re ready to see the correct answers, then click “Show actual meanings” below! |

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | {| class={{"}}mw-collapsible mw-collapsed{{"}} data-expandtext={{"}}Show actual meanings{{"}} data-collapsetext={{"}}Hide actual meanings{{"}} | ||

| | | | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | + | {{Key:A Menu Lost in Translation}} | |

| − | + | |}</nomobile><mobileonly>And if you’re ready to see the correct answers, click on the link below! | |

| − | |||

| − | + | '''[[Key:A Menu Lost in Translation|Show actual meanings]]'''</mobileonly> | |

| − | The | + | {{Nawigacja|poprz=Epic Cooking: The Decorous Rite of the Mushroom Hunt|nast=Of This Ye Shall Not Eat for It Is an Abomination}} |

| − | + | [[Category: Advocaat]] | |

| − | + | [[Category: Advocaat ice cream]] | |

| − | + | [[Category: Apple fritters]] | |

| − | + | [[Category: Avocado]] | |

| − | + | [[Category: Buckwheat]] | |

| − | + | [[Category: Crayfish]] | |

| − | + | [[Category: Dumplings]] | |

| − | + | [[Category: Eggs]] | |

| − | + | [[Category: Feta]] | |

| − | + | [[Category: Herring]] | |

| − | + | [[Category: Mushrooms]] | |

| − | + | [[Category: Pickled cucumber]] | |

| − | + | [[Category: Polish-style roasted chicken]] | |

| − | + | [[Category: Sugar]] | |

| − | + | [[Category: Rum]] | |

| − | + | [[Category: Reading sauce]] | |

| − | + | [[Category: Spinach]] | |

| − | + | [[Category: Wine]] | |

| − | + | [[Category: James Cocks]] | |

| − | + | [[Category: Brazil]] | |

| − | + | [[Category: Netherlands]] | |

| − | + | [[Category: Mexico]] | |

| − | + | [[Category: United Kingdom]] | |

| − | + | [[Category: Early Modern Period]] | |

| − | + | [[Category: 19th century]] | |

| − | + | [[Category: 20th century]] | |

| − | + | [[Category: Recipës]] | |

| − | + | [[pl:Czy macie menu po angielsku?]] | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

Latest revision as of 16:11, 13 May 2024

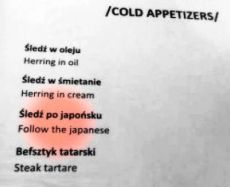

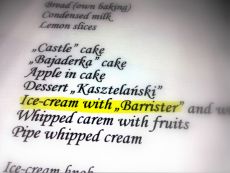

On this first day of April, I’d like to propose a special dinner menu composed entirely of authentic Polish specialities. All of these dishes have been gleaned from actual English-language menus of various restaurants across Poland. Enjoy!

|

Oops, it looks like someone used a machine translator to render the Polish menu into English!

Believe it or not, even some relatively upscale restaurants do this without even having the menu proof-read by someone who actually speaks English. The results are sometimes hilarious, sometimes just confusing, and some are downright off-putting to any visiting foreign tourist. But I kid you not: all of the items in the menu above are inspired by real-life mistranslations which found their way into actual bills of fare.

So, have you figured out what they were supposed to mean? You can type your guesses as comments to this Facebook post. Unless you speak Polish, then you don’t need to guess; but in that case, please don’t spoil the fun!

Follow the JapaneseLet’s start with where the confusion came from. The Polish word “śledź”🔊 is the imperative mood of the verb “śledzić”, meaning “to follow”, “to trace” or “to spy”. But it’s also got another meaning, completely unrelated, which would be more fitting in this context: it’s “herring”. So a better translation of “śledź po japońsku” would have been “herring in the Japanese style”. Now what the heck is that? The “Japanese-style” herring is a very appetising appetiser that was quite popular in Communist Poland. The recipë largely boils down to wrapping a marinated herring fillet around a hard-boiled egg. Perhaps the idea of wrapping a piece of uncooked fish around something reminded one Polish chef of maki sushi rolls, giving rise to its association with Japanese cuisine? Otherwise, this Polish invention has about as much to do with Japan as Hawaiian pizza has to do with Hawaii. The egg and the fish are typically arranged on a bed of canned green peas laced with mayo and decorated with slices of onions and pickles. The marriage of fishy, salty, sour and fatty flavours means that this simple hors d’œuvre pairs perfectly with a shot of cold neat vodka.  Japanese-style herrings by Mr. and Mrs. Straga

Dumplings with Spinach and CelebrationAfter the cold starter it’s time for a hot one: pierogi ze szpinakiem i fetą, or dumplings with spinach and, um… celebration? Pierogi, the delicious Polish filled and boiled dumplings, often go hand in hand with celebration, fair enough. A platter of pierogi is a must on a Polish Christmas Eve table. In fact, the very word “pierogi” comes from “*pirŭ”, the Proto-Slavic term for a feast. Pierogi are a celebratory food par excellence. But the spinach in our pierogi wasn’t mixed with feta, the Polish equivalent of a fête, but with feta, the Greek brined cheese. While not as classic as potato-and-cheese, ground-meat or mushroom-and-kraut varieties, spinach combined with feta cheese and some garlic makes another tasty and popular pierogi filling. And, well, it could have been worse as far as mistranslations go. After all, it’s not only Polish businesses catering to English-speaking patrons that make translation mistakes; the same may happen to U.S. businesses selling supposedly Polish food to Polish Americans. Like the one that confused the Polish words “szpinak” (“spinach”) and “spinacz” (“paper clip”). Office-supplies-filled dumplings, anyone?

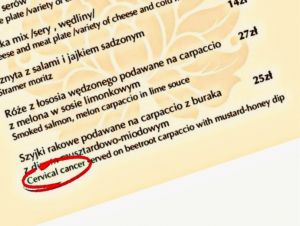

Cervical Cancer SoupNo Polish dinner is complete without a bowl of soup, so now, after we’ve had our starters, what would you say to the exquisite 19th-century Polish delicacy known as cervical cancer soup? Wait, what? A British tourist in Poznań who once found another “cervical cancer” dish on the menu had this to say about the experience:

The restaurant’s spokesperson said they would be “having a word with [their] translator”. By which, I suppose, they meant they would be trying to hold a conversation with Google Translate. Let’s see what happened here, step by step. The original Polish name for the key ingredient is “szyjki rakowe”🔊. “Szyjki” could be literally translated as “little necks”, but in this case it refers to crayfish tails (which, technically, are neither tails nor necks, but abdomina). “Rak”, the Polish word for crayfish, is also used for most of the things which the English language refers to by the Latin word for “crab”, that is, “cancer” – such as the Zodiac sign and, yes, the disease too. And specifically, “rak szyjki macicy”, or “cancer of the neck of the womb”, is the Polish medical term for cervical cancer. “Szyjki rakowe” and “rak szyjki” may look and sound similar, but the difference in meaning is that between delicious and disgusting. In any case, if you’ve never sampled zupa z szyjek rakowych, or crayfish soup (and you still haven’t lost your appetite), then you definitely should give this classic Polish dish a try! Throwing the poor crustaceans live into boiling water may seem cruel, but it’s actually the most humane way of killing them as they die instantly.

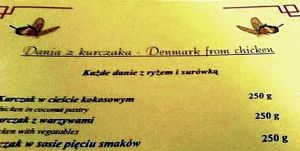

Denmark from ChickenAnd now for the main course, Denmark from chicken. Is this some kind of Nordic version of chicken Kiev (or is it chicken Kyiv)? Not really. You see, “Dania”🔊 (with capital D) is the Polish name for the country of Denmark. But “dania”🔊 (with lower-case D and a marginally different pronunciation) is the Polish word for dishes or courses. So “dania z kurczaka” is not so much a single preparation as it’s the title of a whole section of a menu, devoted to chicken dishes in general. And it has nothing whatsoever to do with the state of Denmark. I suppose you still expect a recipë, though, don’t you? Okay, so let’s pick what is perhaps the most Polish chicken dish you can find, which is the kurczę pieczone po polsku, or liver-stuffed roasted chicken in the Polish style.

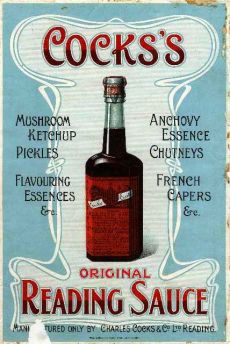

Buckwheat with Cocks SauceThis one sounds intriguing, doesn’t it? Some older folks in England might remember Cocks’s Reading Sauce. And no, it wasn’t used to make reading about cocks more enjoyable. It was a brand of fish sauce produced in the Berkshire town of Reading by a fishmonger whose name was James Cocks (and his heirs after him). First marketed in 1802, it was made from fermented anchovies, walnut ketchup, mushroom ketchup, soy sauce, salt, garlic and chilli peppers[1] (see my older post for more about the intertwined histories of ketchup and fish sauce). It was soon followed by and for decades competed with similar sauces, also sold in small bottles with orange labels, like the now more famous Worcestershire sauce. But eventually, the production of Reading sauce ended in 1962.[2] So it’s unlikely that this is the sauce that was meant by the menu I once saw in a Polish roadside inn. Besides, while Cocks’s condiment was advertised to go well with “game, wild fowl, hashes, rump steaks and cold meat”,[3] it was never known to be put on heaps of boiled buckwheat. Back to square one then. A better explanation would be that the “cocks sauce” in the menu was a result of mistranslation. The English word “cocks” has multiple meanings and so do the Polish terms “kury”🔊 and “kurki”🔊. The primary meaning of “cocks” is “male domestic fowl”, also known as “cockerels” or “roosters”. In modern Polish, “kury” refers to hens, but a few centuries ago it meant “roosters” instead. So was the sauce made from the meat of cockerels? Well, no. Among the many different meanings of the English “cock”, the vulgar term for the male member is particularly well known. The rooster has been a symbol of male virility in many cultures. Among Slavic languages, Bulgarian makes the same association, with “kur” referring to both the cocky bird and a man’s cock (“patka” – literally, “duck” – is another vulgar Bulgarian word for the latter, which makes Bulgarians laugh every time they hear “kuropatka” – which means “partridge” in Russian and “cock-dick” in Bulgarian; gotta love these Slavic false friends). “Kur” also gave rise to the vulgar word for a prostitute (a woman whose job involves handling penes) in all Slavic languages, including Polish. But I digress; the sauce definitely wasn’t made from phalli! Besides, the Polish word was “kurki”, a diminutive form of “kury”. Depending on the context, it could mean freshly hatched chickens, weathercocks, stopcocks,… But none of these seem to fit in the context of sauce for buckwheat. So what does? Chanterelles. Small, peppery, trumpet-shaped mushrooms. Their bright yellow colour might remind you of chicks, which explains why “kurki” is the common Polish name for them (see this older post for more about Polish forest mushrooms). So there you have it: kasza z sosem kurkowym is buckwheat with chanterelle sauce.  Buckwheat with Recipë and picture from the Polish cooking blog Trzeci Talerz.

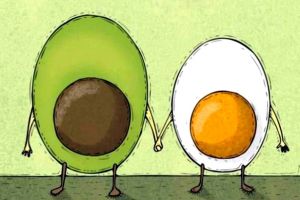

Ice Cream with BarristerWould you like your lawyer to come along with your order of ice cream? If not, then don’t worry; this is just another botched translation. The original Polish phrase is “lody z adwokatem”, where “adwokat”🔊 is the word that threw the machine translator off. In one sense, it does refer to a lawyer that advocates your case in a court of law, coming from the Latin word “advocatus”, “the one who has been called to one’s aid”. But in this case, “adwokat” is just a Polonised spelling of the Dutch “advocaat”, which refers to a sweet, smooth, custardy yellow drink made from yolks, sugar and alcohol. Nobody really knows why this egg liqueur is called that. One hypothesis says it was Dutch lawyers’ beverage of choice. But there’s a more curious one, which claims that the name of the drink ultimately comes from a Native American word for testicles.

When the Spaniards (not Dutch) conquered Mexico and discovered the fruit, they assimilated its Nahuatl name, “āhuacatl”, into their own language as “aguacate”. This was later borrowed into French as “avocat” (which incidentally also means “lawyer”) and into English, Dutch and many other European languages as “avocado”. But there’s quite a lot to unpack here. What does the avocado have to do with an egg-based liqueur? Why did Dutch settlers in Recife, Brazil, make a drink from a fruit that is native to Mexico? What did Dutch settlers do in Brazil in the first place? And is the avocado really named after testicles? Let’s start with that last claim. Is it true? You bet it is – just as true as the fact that fruits with a hard shell around an edible kernel are called “nuts”, because that’s one of the English words for testicles, which these fruits bear an uncanny resemblance to. Or that the Polish word “jajka” refers to both eggs and testicles, because the former look like the latter. So in a nutsack, I mean, nutshell, it’s true, but only in reverse. In fact, “avocado” is the primary meaning of “āhuacatl” in Nahuatl (the language of the Aztecs), but the same word may have been used as a Nahuatl slang term for balls.[4] As for Dutch settlers in Brazil, they actually have a pretty long history. In the first half of the 17th century, the north-east coast of Brazil was a Dutch colony known, quite unimaginatively, as New Holland. Its capital city was Mauritsstad, or Recife, now the capital of the state of Pernambuco. Even after the Portuguese recaptured Recife in 1654, Dutch migration to Brazil continued well into the 20th century. What made Pernambuco attractive to both the Dutch and the Portuguese were its extensive sugar cane plantations (worked by African slaves). Sugar and rum – both made from sugar cane – are two of the three ingredients of advocaat. But what about the third? If what some sources, such as The Oxford Companion to Sugar and Sweets, say is true, then avocado was the original third ingredient, which lent advocaat its name. This Mexican fruit was introduced to Brazil in the early 19th century and has been grown there ever since.[5] And so, someone in Brazil combined avocado pulp, rum and sugar into a thick, sweet alcoholic drink that would find favour with the Dutch Brazilians and later, with the Dutch in the Netherlands. Attempts at recreating the drink in Europe led some Dutchperson to replace the avocado (which doesn’t grow in Europe) with yolk.[6] The colour was different, but the texture may have been similar. Now, is it true? I don’t know; it’s not entirely implausible, but seems like a bit of a stretch to me. But hey, it’s April Fool’s, so yeah, 100% confirmed! Making ice cream with advocaat may be as simple as buying a bucket of ice cream and pouring the egg liqueur on top. But if you’d like something a little more involved, then here’s a recipë for home-made advocaat-flavoured ice cream.

Apple Pie GuiltyYou may have wanted to keep the barrister from the cold dessert, as apparently the hot dessert has been found guilty! Let’s just hope the only thing the apple pie has been convicted of is being a guilty pleasure. The one who’s really guilty here is the restaurant owner who tried to cut corners by using unverified machine translation. The Polish adjective “winny”🔊 has at least two meanings. In one sense, it comes from the noun “wina”, which translates as “guilt, fault or blame”. But in another sense, it derives from the completely unrelated word “wino”, which means “wine”. “Winey” makes much more sense in the culinary context than “guilty”. “Ciasto” (“cieście” in the locative case) is another problematic word. It may refer to a pie or cake, but also to uncooked dough or batter. As it turns out, jabłka w cieście winnym isn’t a pie at all; it’s apple fritters made by dunking apple slices in wine-infused batter before deep-frying them. And here’s a recipë for the final dish of our mistranslated meal.

References

|

| ◀️ Previous | 📜 List of posts | Next ▶️ |

| ⏮️ First | 🎲 Random post | Latest ⏭️ |