Difference between revisions of "Epic Cooking: The Decorous Rite of the Mushroom Hunt"

m (clean up) |

|||

| Line 24: | Line 24: | ||

}}</ref> the Poles, along with other Balto-Slavic nations and northern Italians, belong to ''mycophillic'', or mushroom-loving, peoples. On the other end of the spectrum are ''mycophobic'' nations, which in Europe are mostly concentrated in the North Sea basin and whose risk acceptance in regards to mushroom picking only goes as far as picking up a plastic box of cultivated champignons in a supermarket. | }}</ref> the Poles, along with other Balto-Slavic nations and northern Italians, belong to ''mycophillic'', or mushroom-loving, peoples. On the other end of the spectrum are ''mycophobic'' nations, which in Europe are mostly concentrated in the North Sea basin and whose risk acceptance in regards to mushroom picking only goes as far as picking up a plastic box of cultivated champignons in a supermarket. | ||

| − | Mycophobes may find the Polish passion for gathering, preserving and consuming wild mushrooms shockingly adventurous, foolhardy even. Isn’t it dangerous? Well, yes, mushroom poisoning does occur more often in Poland than it does in countries where mushroom picking simply isn’t a thing. But hardly as common as you might think. Within five years from 2009 to 2013, only eight people in western and central Poland died from mushroom poisoning (compared to 112 people who died from various alcohols, including 49 from methanol, and 95 who died from pharmaceutical drug overdose).<ref>As reported by six out of | + | Mycophobes may find the Polish passion for gathering, preserving and consuming wild mushrooms shockingly adventurous, foolhardy even. Isn’t it dangerous? Well, yes, mushroom poisoning does occur more often in Poland than it does in countries where mushroom picking simply isn’t a thing. But hardly as common as you might think. Within five years from 2009 to 2013, only eight people in western and central Poland died from mushroom poisoning (compared to 112 people who died from various alcohols, including 49 from methanol, and 95 who died from pharmaceutical drug overdose).<ref>As reported by six out of Poland’s ten toxicological centres. {{Cyt |

| tytuł = International Journal of Occupational Medicine and Environmental Health | | tytuł = International Journal of Occupational Medicine and Environmental Health | ||

| nazwisko r = Krakowiak ''et al.'' | | nazwisko r = Krakowiak ''et al.'' | ||

| Line 49: | Line 49: | ||

}}</ref> Many field guides – printed and online – are available too. But most Polish mushroomers learn to recognise fungal species from their parents or grandparents, and continue to gather the same few kinds of mushrooms (even though many more are edible too) which they learned to pick when they were children. Field guides do little to expand their preferences; they only seem to unify mushroom names used throughout the country.<ref>''Ibid.'', p. 332</ref> | }}</ref> Many field guides – printed and online – are available too. But most Polish mushroomers learn to recognise fungal species from their parents or grandparents, and continue to gather the same few kinds of mushrooms (even though many more are edible too) which they learned to pick when they were children. Field guides do little to expand their preferences; they only seem to unify mushroom names used throughout the country.<ref>''Ibid.'', p. 332</ref> | ||

| − | [[File:{{#setmainimage:Iwan Ł. Gorochow, Grzyby.jpg}}|thumb|left|'' | + | [[File:{{#setmainimage:Iwan Ł. Gorochow, Grzyby.jpg}}|thumb|left|''“From the grove comes the whole company, carrying… wicker baskets full of mushrooms…”''<ref>{{Cyt |

| nazwisko = Mickiewicz | | nazwisko = Mickiewicz | ||

| imię = Adam | | imię = Adam | ||

| inni = translated by Marcel Weyland | | inni = translated by Marcel Weyland | ||

| − | | tytuł = Pan Tadeusz, or The Last Foray in Lithuania: A Tale of the Gentry during 1811-1812 | + | | tytuł = Pan Tadeusz, or The Last Foray in Lithuania: A Tale of the Gentry during 1811-1812 |

| url = https://web.archive.org/web/20170707131534/http://www.antoranz.net/BIBLIOTEKA/PT051225/PanTad-eng/PT-Start.htm#CONTENTS | | url = https://web.archive.org/web/20170707131534/http://www.antoranz.net/BIBLIOTEKA/PT051225/PanTad-eng/PT-Start.htm#CONTENTS | ||

}}, Book III, verses 691–694</ref><br>{{small|Painted by Ivan L. Gorokhov (1912)}}]] | }}, Book III, verses 691–694</ref><br>{{small|Painted by Ivan L. Gorokhov (1912)}}]] | ||

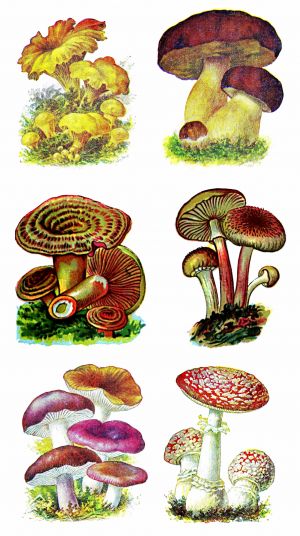

So which mushrooms are most commonly picked in Poland? | So which mushrooms are most commonly picked in Poland? | ||

| − | * The '''king bolete''' (''Boletus edulis''), also known as | + | * The '''king bolete''' (''Boletus edulis''), also known as “penny bun”, “cep” or “porcino”, reigns supreme. In Polish, it’s known as ''“borowik szlachetny”'' (literally, “noble pine-forest mushroom”) or ''“prawdziwek”'' (“true mushroom”). |

| − | * The '''bay bolete''' (''Imleria badia'') is related, but less prized. Its second-best status is reflected in its Polish name, '' | + | * The '''bay bolete''' (''Imleria badia'') is related, but less prized. Its second-best status is reflected in its Polish name, ''“podgrzybek”'', which may be translated as “deputy mushroom” or “junior mushroom”. It’s popular enough in Poland that the Russians call it ''“polskiy grib”'', or “Polish mushroom”. |

| − | * The '''golden chanterelle''' (''Cantharellus cibarius''), a bright-yellow trumpet-shaped mushroom with a slightly peppery flavour, called '' | + | * The '''golden chanterelle''' (''Cantharellus cibarius''), a bright-yellow trumpet-shaped mushroom with a slightly peppery flavour, called ''“kurka”'' (“little chick”) or ''“pieprznik”'' (“pepper mushroom”) in Polish, comes last on the podium. Mickiewicz referred to it as ''“lisica”'', or “vixen”. |

Further spots are taken by: | Further spots are taken by: | ||

| − | * various species of '''slippery jacks''' (genus ''Suillus''), which the Poles refer to as '' | + | * various species of '''slippery jacks''' (genus ''Suillus''), which the Poles refer to as ''“maślaki”'' (“butterballs”) because of their slimy caps; |

| − | * '''saffron milk cap''' (''Lactarius deliciosus''), a red-brownish mushroom which oozes a milky liquid when damaged; its Polish name is '' | + | * '''saffron milk cap''' (''Lactarius deliciosus''), a red-brownish mushroom which oozes a milky liquid when damaged; its Polish name is ''“rydz”'', or “ginger-coloured mushroom”; |

| − | * '''parasol mushroom''' (''Macrolepiota procera''), or '' | + | * '''parasol mushroom''' (''Macrolepiota procera''), or ''“kania”'' in Polish, whose broad flat cap may be fried in bread crumbs like a pork cutlet; |

| − | * '''honey mushroom''' (''Armillaria mellea''), small and sweetish, which grows in patches on tree stumps; its Polish name is '' | + | * '''honey mushroom''' (''Armillaria mellea''), small and sweetish, which grows in patches on tree stumps; its Polish name is ''“opieńka miodowa”'', or “honey stumper”; |

| − | * some species of '''knight caps''' (genus ''Tricholoma''), known in Polish as '' | + | * some species of '''knight caps''' (genus ''Tricholoma''), known in Polish as ''“gąski”'', or “little geese”. |

Mushroom season lasts from late summer to mid-autumn, but Polish people preserve most of the fungi they collect, so that they can enjoy them all year long. This they do mostly by drying and to a lesser extent by pickling in vinegar (mostly in the case of slippery jacks and other species which don’t lend themselves to drying) or, less traditionally, freezing. The Poles typically gather mushrooms for their own use, but they face competition from professional gatherers who, though less numerous (only 1% of all mushroomers), pick much larger quantities than recreational mushroom hunters do.<ref name=cbos/> | Mushroom season lasts from late summer to mid-autumn, but Polish people preserve most of the fungi they collect, so that they can enjoy them all year long. This they do mostly by drying and to a lesser extent by pickling in vinegar (mostly in the case of slippery jacks and other species which don’t lend themselves to drying) or, less traditionally, freezing. The Poles typically gather mushrooms for their own use, but they face competition from professional gatherers who, though less numerous (only 1% of all mushroomers), pick much larger quantities than recreational mushroom hunters do.<ref name=cbos/> | ||

| − | This is the situation today. And what was it like in the past? | + | This is the situation today. And what was it like in the past? “Mushrooming’s ancient and decorous rite” is described with great beauty in ''Pan Tadeusz'', the Polish national epic written by Adam Mickiewicz (pronounced {{pron|meets|kyeh|veetch}}) in 1834. So let’s pay yet another visit to the fictional manor of Soplicowo ({{pron|saw|plee|tsaw|vaw}}) and see what kinds of mushrooms the epic’s characters gathered and what use they later put them to. |

== “There Were Mushrooms Aplenty” == | == “There Were Mushrooms Aplenty” == | ||

| − | [[File:KostrzewskiFranciszek.Grzybobranie.1860.jpg|thumb|upright=1.3|'' | + | [[File:KostrzewskiFranciszek.Grzybobranie.1860.jpg|thumb|upright=1.3|''“They from breakfast, so noisily bright, turned to mushrooming’s ancient and decorous rite…”''<ref>''Ibid.'', Book III, verses 245–246</ref><br>{{small|Painted by Franciszek Kostrzewski (ca. 1860)}}]] |

{{ Cytat | {{ Cytat | ||

| <poem>A small grove, sparsely wooded, now came into sight; | | <poem>A small grove, sparsely wooded, now came into sight; | ||

| Line 84: | Line 84: | ||

Looking down, his eyes only he swivels around; | Looking down, his eyes only he swivels around; | ||

That one looks straight ahead, and steps as if asleep, | That one looks straight ahead, and steps as if asleep, | ||

| − | Neither left nor right veering, a straight line would keep, | + | Neither left nor right veering, a straight line would keep, |

All, often, and at random, bend down very low, | All, often, and at random, bend down very low, | ||

As if reverence to fellow forms wishing to show.</poem> | As if reverence to fellow forms wishing to show.</poem> | ||

| Line 91: | Line 91: | ||

| imię = Adam | | imię = Adam | ||

| inni = translated by Marcel Weyland | | inni = translated by Marcel Weyland | ||

| − | | tytuł = Pan Tadeusz, or The Last Foray in Lithuania: A Tale of the Gentry during 1811-1812 | + | | tytuł = Pan Tadeusz, or The Last Foray in Lithuania: A Tale of the Gentry during 1811-1812 |

| url = https://web.archive.org/web/20170707131534/http://www.antoranz.net/BIBLIOTEKA/PT051225/PanTad-eng/PT-Start.htm#CONTENTS | | url = https://web.archive.org/web/20170707131534/http://www.antoranz.net/BIBLIOTEKA/PT051225/PanTad-eng/PT-Start.htm#CONTENTS | ||

| − | }}, Book III, verses 220–236<br>* The action takes place in early September (of 1811), at the height of mushroom season. The Polish adjective '' | + | }}, Book III, verses 220–236<br>* The action takes place in early September (of 1811), at the height of mushroom season. The Polish adjective ''“majowych”'', here mistranslated as “of May”, was actually used by Mickiewicz in the now largely forgotten sense of “vividly green”. |

| oryg = <poem>Był gaj z rzadka zarosły, wysłany murawą; | | oryg = <poem>Był gaj z rzadka zarosły, wysłany murawą; | ||

Po jej kobiercach, na wskroś białych pniów brzozowych, | Po jej kobiercach, na wskroś białych pniów brzozowych, | ||

| Line 116: | Line 116: | ||

}} }} | }} }} | ||

| − | The whole affair began when Lady Telimena, bored by the men’s heated argument about hare hunting at [[Epic Cooking: Breakfast at Judge | + | The whole affair began when Lady Telimena, bored by the men’s heated argument about hare hunting at [[Epic Cooking: Breakfast at Judge Soplica’s|breakfast]], declared that she was going out to gather saffron milk caps, then took Lord Chamberlain’s youngest daughter by the hand and left. Judge Soplica saw this as an opportunity to calm his guests down and announced a mushroom-picking competition: |

{{ Cytat | {{ Cytat | ||

| Line 122: | Line 122: | ||

Who with the best milk cap to the table returns, | Who with the best milk cap to the table returns, | ||

His place next to the loveliest of ladies he earns; | His place next to the loveliest of ladies he earns; | ||

| − | He will choose her himself. If a lady’s the winner, | + | He will choose her himself. If a lady’s the winner, |

She the handsomest fellow can partner at dinner.”</poem> | She the handsomest fellow can partner at dinner.”</poem> | ||

| − | | źródło = A. Mickiewicz, ''op. cit.'', Book II, verses 846–850; own paraphrase of M. | + | | źródło = A. Mickiewicz, ''op. cit.'', Book II, verses 846–850; own paraphrase of M. Weyland’s translation |

| oryg = <poem>„Panowie, po grzyby do boru! | | oryg = <poem>„Panowie, po grzyby do boru! | ||

Kto z najpiękniejszym rydzem do stołu przybędzie, | Kto z najpiękniejszym rydzem do stołu przybędzie, | ||

| Line 146: | Line 146: | ||

Fresh or salted, for autumn, or winter use rather, | Fresh or salted, for autumn, or winter use rather, | ||

Put away. But the Tribune, of course, '''fly-bane''' gathered.</poem> | Put away. But the Tribune, of course, '''fly-bane''' gathered.</poem> | ||

| − | | źródło = A. Mickiewicz, ''op. cit.'', Book III, verses 260–269; own paraphrase of M. | + | | źródło = A. Mickiewicz, ''op. cit.'', Book III, verses 260–269; own paraphrase of M. Weyland’s translation |

| oryg = <poem>Grzybów było w bród. Chłopcy biorą krasnolice, | | oryg = <poem>Grzybów było w bród. Chłopcy biorą krasnolice, | ||

Tyle w pieśniach litewskich sławione '''lisice''', | Tyle w pieśniach litewskich sławione '''lisice''', | ||

| Line 166: | Line 166: | ||

Kerchiefs knotted at corners, or small wicker baskets | Kerchiefs knotted at corners, or small wicker baskets | ||

Full of mushrooms; young ladies displayed in one hand | Full of mushrooms; young ladies displayed in one hand | ||

| − | The imposing '''boletus''', a well-folded fan, | + | The imposing '''boletus''', a well-folded fan, |

| − | In the other hand, tied like a field-flower posy, | + | In the other hand, tied like a field-flower posy, |

'''Brittlegills''' and some '''stumpers''', brown, ochre, and rosy. | '''Brittlegills''' and some '''stumpers''', brown, ochre, and rosy. | ||

The Tribune carried '''fly-bane'''. </poem> | The Tribune carried '''fly-bane'''. </poem> | ||

| − | | źródło = A. Mickiewicz, ''op. cit.'', Book III, verses 691–698; own paraphrase of M. | + | | źródło = A. Mickiewicz, ''op. cit.'', Book III, verses 691–698; own paraphrase of M. Weyland’s translation |

| oryg = <poem>Więc z gaju | | oryg = <poem>Więc z gaju | ||

Wychodziła gromada, niosąca krobeczki, | Wychodziła gromada, niosąca krobeczki, | ||

| Line 182: | Line 182: | ||

<mobileonly>[[File:Grzyby w Panu Tadeuszu.jpg|thumb|Mushroom species collected in the forest of Soplicowo:<br>chanterelles, king boletes (penny buns),<br>saffron milk caps, stumpers (honey mushrooms),<br>brittlegills and fly agarics (poisonous)]]</mobileonly> | <mobileonly>[[File:Grzyby w Panu Tadeuszu.jpg|thumb|Mushroom species collected in the forest of Soplicowo:<br>chanterelles, king boletes (penny buns),<br>saffron milk caps, stumpers (honey mushrooms),<br>brittlegills and fly agarics (poisonous)]]</mobileonly> | ||

| − | All in all, there are five edible kinds of mushrooms (the fly agaric, here translated as | + | All in all, there are five edible kinds of mushrooms (the fly agaric, here translated as “fly-bane”, is poisonous). The one we haven’t discussed yet is the '''brittlegill''', which in fact refers to several species of the genus ''Russula''. Mickiewicz calls them by the word ''“surojadki”'' (“eaten raw”), but the Polish term that is more common today is ''“gołąbki”'', or “little pigeons”. They’re edible, but often ignored nowadays, as their taste is just okay and, having gills rather than pores on the underside of the cap, they can be confused with some toxic species. |

== Mushroom War == | == Mushroom War == | ||

| − | A small digression before we move on: what is this song which calls the king bolete | + | A small digression before we move on: what is this song which calls the king bolete “the colonel of mushrooms”? According to the poet’s explanatory note, it’s “a folk song well known in Lithuania about mushrooms marching to war under a king bolete’s command. This song describes the characteristics of edible mushrooms.”<ref>''Ibid.'', explanatory notes; own translation</ref> Why did the author of a Polish epic draw inspiration from Lithuanian folklore? Because the Grand Duchy of Lithuania is where the story is set; in fact, the epic’s very first words are “Lithuania, my country”.<ref>''Ibid.'', Book I, verse 1</ref> In the poet’s time, the Grand Duchy was a part of the Russian Empire that was inhabited by Polish-speaking nobility (which he belonged to himself), Belarusian or Lithuanian-speaking peasants and Yiddish-speaking Jews. |

Anyway, Mickiewicz didn’t quote the song directly. But, as luck would have it, Mickiewiczologists were able to track down, more than a hundred years ago, its original Lithuanian-language lyrics. Here it goes, as noted down by Mr. and Mrs. Angrabaitis in what is now Lithuania’s Marijampolė County: | Anyway, Mickiewicz didn’t quote the song directly. But, as luck would have it, Mickiewiczologists were able to track down, more than a hundred years ago, its original Lithuanian-language lyrics. Here it goes, as noted down by Mr. and Mrs. Angrabaitis in what is now Lithuania’s Marijampolė County: | ||

| − | [[File:Mushroom Wars.png|thumb|'' | + | [[File:Mushroom Wars.png|thumb|''“Mushrooms all, gather for war, the Great Mushroom War!”''<br>{{small|Graphic from the video game ''Mushroom Wars 2'' (2016)}}]] |

{{ Cytat | {{ Cytat | ||

| <poem>What did the little hare say when running through the wood? | | <poem>What did the little hare say when running through the wood? | ||

| Line 195: | Line 195: | ||

:'''Red-Capped Stalk''' thus answered him, “Me, I’m young and bachelor still, | :'''Red-Capped Stalk''' thus answered him, “Me, I’m young and bachelor still, | ||

:So I’m not going to war, the Great Mushroom War!” | :So I’m not going to war, the Great Mushroom War!” | ||

| − | '''Saffron Milk Cap''' then replied, “I’m a maiden and that’s why | + | '''Saffron Milk Cap''' then replied, “I’m a maiden and that’s why |

I shall not be going to war, the Great Mushroom War!” | I shall not be going to war, the Great Mushroom War!” | ||

:'''Slippery Jack''', the good-for-nought, told the hare just what he thought, | :'''Slippery Jack''', the good-for-nought, told the hare just what he thought, | ||

| Line 226: | Line 226: | ||

}}, own translation }} | }}, own translation }} | ||

| − | As you can see, apart from the species mentioned in ''Pan Tadeusz'', such as saffron milk caps, king boletes and stumpers (honey mushrooms), the song also mentioned other edible, if less prized, mushrooms: the '''red-capped scaber stalk''' (''Leccinum aurantiacum'') and the slippery jack. It could also be that the Lithuanian word '' | + | As you can see, apart from the species mentioned in ''Pan Tadeusz'', such as saffron milk caps, king boletes and stumpers (honey mushrooms), the song also mentioned other edible, if less prized, mushrooms: the '''red-capped scaber stalk''' (''Leccinum aurantiacum'') and the slippery jack. It could also be that the Lithuanian word ''“zuikužėlis”'' refers, in this case, not to a hare running around the forest, but to any of the mushrooms whose Lithuanian folk names derive from the word for “bunny”. These include the quite edible '''birch bolete''' (''Leccinum scabrum'') and the very inedible '''bitter bolete''' (''Tylopilus felleus''; this one is also known as ''“zajączek gorzki”'', or “bitter bunny”, in Polish).<ref> {{Cyt |

| tytuł = Res Humanitariae | | tytuł = Res Humanitariae | ||

| nazwisko r = Lubienė | | nazwisko r = Lubienė | ||

| Line 239: | Line 239: | ||

}}</ref> In any case, it’s quite possible that in Mickiewicz’s time the song had more verses and served as a real oral field guide to be sung while picking mushrooms. | }}</ref> In any case, it’s quite possible that in Mickiewicz’s time the song had more verses and served as a real oral field guide to be sung while picking mushrooms. | ||

| − | While we’re digressing, let’s clarify one more thing: why did the Tribune gather fly agarics, the most recognizable of toxic toadstools? Was it just to show his contempt for any forest activity that didn’t involve hunting big game, the only pastime he thought becoming of a nobleman? Or did he intend to poison somebody? Or something. As we already know, [[Epic Cooking: The Perfect Cook#“Hreczecha is My Name”|the Tribune absolutely hated flies]]. And the '''fly agaric''' (''Amanita muscaria''), as both its English and Polish names imply (Polish '' | + | While we’re digressing, let’s clarify one more thing: why did the Tribune gather fly agarics, the most recognizable of toxic toadstools? Was it just to show his contempt for any forest activity that didn’t involve hunting big game, the only pastime he thought becoming of a nobleman? Or did he intend to poison somebody? Or something. As we already know, [[Epic Cooking: The Perfect Cook#“Hreczecha is My Name”|the Tribune absolutely hated flies]]. And the '''fly agaric''' (''Amanita muscaria''), as both its English and Polish names imply (Polish ''“muchomor”'' literally means “fly-bane”), was used as insecticide for centuries. This is how: |

{{ Cytat | {{ Cytat | ||

| − | | Dice a fresh fly agaric and cook it in boiling milk. Then pour the milk into cups for the flies [to drink] or smear it in the gaps where bedbugs are. | + | | Dice a fresh fly agaric and cook it in boiling milk. Then pour the milk into cups for the flies [to drink] or smear it in the gaps where bedbugs are. |

| oryg = Pokrajana w kawałki świeża bedłka muchomorowa gotuje się w mleku, a mleko to rozlewa się na miseczki dla much lub smaruje nim szpary, gdzie pluskwy siedzą. | | oryg = Pokrajana w kawałki świeża bedłka muchomorowa gotuje się w mleku, a mleko to rozlewa się na miseczki dla much lub smaruje nim szpary, gdzie pluskwy siedzą. | ||

| źródło = {{Cyt | | źródło = {{Cyt | ||

| Line 259: | Line 259: | ||

== Recipës == | == Recipës == | ||

| − | [[File:Tomasz Łosik - Promenade dans la forêt.jpg|thumb|upright|'' | + | [[File:Tomasz Łosik - Promenade dans la forêt.jpg|thumb|upright|''“Hands empty came then Telimena, with both of her young gentlemen.”''<ref>A. Mickiewicz, ''op. cit.'', Book III, verses 698–699</ref><br>{{small|Painted by Tomasz Łosik (1883)}}]] |

In the end, a bell called the mushroom hunters back to the manor for lunch. Even though originally the hunt had been Telimena’s idea, she must have been, as the Notary observed, looking for mushrooms in the trees, as she returned empty-handed from the wood. So did her two suitors, Thaddeus and the Count. We don’t know who won the Judge’s competition. Nor does the poem mention what happened with the mushrooms others had collected. We can only guess. | In the end, a bell called the mushroom hunters back to the manor for lunch. Even though originally the hunt had been Telimena’s idea, she must have been, as the Notary observed, looking for mushrooms in the trees, as she returned empty-handed from the wood. So did her two suitors, Thaddeus and the Count. We don’t know who won the Judge’s competition. Nor does the poem mention what happened with the mushrooms others had collected. We can only guess. | ||

| Line 266: | Line 266: | ||

Eventually, the mushrooms must have ended up on the nobles’ table. But in what form? The poet didn’t say; there is no mention of any mushroom-containing dishes anywhere in ''Pan Tadeusz''. But that shouldn’t stop us from speculating about what mushroom dishes they could have enjoyed – based on cook books from the same period. | Eventually, the mushrooms must have ended up on the nobles’ table. But in what form? The poet didn’t say; there is no mention of any mushroom-containing dishes anywhere in ''Pan Tadeusz''. But that shouldn’t stop us from speculating about what mushroom dishes they could have enjoyed – based on cook books from the same period. | ||

| − | [[File:Karolina z Potockich Nakwaska.png|thumb|left|upright=.6|Karolina Nakwaska (1798–1875), author of a home-making book (among other works)]] | + | [[File:Karolina z Potockich Nakwaska.png|thumb|left|upright=.6|Karolina Nakwaska (1798–1875), author of a home-making book (among other works)]] |

| − | Let’s start with the saffron milk caps, which Mickiewicz considered to | + | Let’s start with the saffron milk caps, which Mickiewicz considered to “have the best taste”. His friend, Karolina Nakwaska, who wrote a home-making book for women, gave a recipë that is perfect in its simplicity. |

{{ Cytat | {{ Cytat | ||

| − | | Take carefully selected, worm-free saffron milk caps, remove the stems; if the caps are too big, then cut them in half. Arrange on a grill over a slow fire, place a small piece of butter in each cap, sprinkle with pepper and salt, and fry without flipping them over. You can use very good olive oil instead of butter. Add chopped parsley and onion. Serve after ten minutes. Saffron milk caps and [other] mushrooms fried simply in butter with onion, pepper and salt, are just perfect. | + | | Take carefully selected, worm-free saffron milk caps, remove the stems; if the caps are too big, then cut them in half. Arrange on a grill over a slow fire, place a small piece of butter in each cap, sprinkle with pepper and salt, and fry without flipping them over. You can use very good olive oil instead of butter. Add chopped parsley and onion. Serve after ten minutes. Saffron milk caps and [other] mushrooms fried simply in butter with onion, pepper and salt, are just perfect. |

| oryg = Weź rydzów starannie wybranych, nierobaczywych, odejm ogonki, jeżeli za duże, przekraj je na dwoje. Postaw na ruszcie na wolny ogień, w środek każdej daj kawałeczek masła, pieprzu i soli, smaż, nie przewracaj; zamiast masła, można je napuszczać bardzo dobrą oliwą, dodawszy pietruszki i cebuli siekanej. Po dziesięciu minutach wydaj. Rydze i grzyby w maśle prosto smażone z cebulką, pieprzem i solą są doskonałe. | | oryg = Weź rydzów starannie wybranych, nierobaczywych, odejm ogonki, jeżeli za duże, przekraj je na dwoje. Postaw na ruszcie na wolny ogień, w środek każdej daj kawałeczek masła, pieprzu i soli, smaż, nie przewracaj; zamiast masła, można je napuszczać bardzo dobrą oliwą, dodawszy pietruszki i cebuli siekanej. Po dziesięciu minutach wydaj. Rydze i grzyby w maśle prosto smażone z cebulką, pieprzem i solą są doskonałe. | ||

| źródło = {{Cyt | | źródło = {{Cyt | ||

| Line 286: | Line 286: | ||

{{clear}} | {{clear}} | ||

{{ Cytat | {{ Cytat | ||

| − | | Cook some fresh king boletes in boiling water, then fry them with onion (as you normally would) and a small piece of dried bouillon; once fried, chop them up as finely as possible. Add four eggs, nutmeg and pepper. Roll out hard-kneaded yeast dough, then fill with the mushrooms as for kołdunki [i.e., pierogi, or filled dumplings], fry in fat until brown and serve hot. | + | | Cook some fresh king boletes in boiling water, then fry them with onion (as you normally would) and a small piece of dried bouillon; once fried, chop them up as finely as possible. Add four eggs, nutmeg and pepper. Roll out hard-kneaded yeast dough, then fill with the mushrooms as for kołdunki [i.e., pierogi, or filled dumplings], fry in fat until brown and serve hot. |

| oryg = Usmażyć z cebulką borowików świeżych uprzednio odgotowanych w wodzie (jak się zwyczajnie smażą), z dodaniem tylko kawałek bulionu suchego [tj. kostki rosołowej]; skoro się usmażą, siekają się jak najdrobniej. Należy wbić cztery jaja, dodać muszkatowej gałki i pieprzu; rozwałkować cienko ciasto drożdżowe, twardo zarobione, potem robić tak, jak kołdunki, nakładając do środka tymi grzybami, odsmażywszy one w tłustości na rumiano, gorąco wydać do stołu. | | oryg = Usmażyć z cebulką borowików świeżych uprzednio odgotowanych w wodzie (jak się zwyczajnie smażą), z dodaniem tylko kawałek bulionu suchego [tj. kostki rosołowej]; skoro się usmażą, siekają się jak najdrobniej. Należy wbić cztery jaja, dodać muszkatowej gałki i pieprzu; rozwałkować cienko ciasto drożdżowe, twardo zarobione, potem robić tak, jak kołdunki, nakładając do środka tymi grzybami, odsmażywszy one w tłustości na rumiano, gorąco wydać do stołu. | ||

| źródło = {{Cyt | | źródło = {{Cyt | ||

| Line 322: | Line 322: | ||

}}</ref> In farming societies, where foraging is no longer the chief source of food, but still helps expand the menu, this division is not only continued, but also expanded to include a class dimension: hunting, treated increasingly as a sport, is the domain of noblemen, while picking berries, nuts and herbs is left to peasants, especially women. In ''Pan Tadeusz'', we can observe a pair of young peasants – a girl and a boy – collecting cowberries and hazelnuts. | }}</ref> In farming societies, where foraging is no longer the chief source of food, but still helps expand the menu, this division is not only continued, but also expanded to include a class dimension: hunting, treated increasingly as a sport, is the domain of noblemen, while picking berries, nuts and herbs is left to peasants, especially women. In ''Pan Tadeusz'', we can observe a pair of young peasants – a girl and a boy – collecting cowberries and hazelnuts. | ||

| − | [[File:Wasilij T. Timofiejew, Dziewczę z malinami.jpg|thumb|upright|'' | + | [[File:Wasilij T. Timofiejew, Dziewczę z malinami.jpg|thumb|upright|''“A pair of cheeks than berries more crimson and fair; they are the maid’s who gathers such nuts and fruit there…”''<ref>''Ibid.'', Book IV, verses 83–84</ref><br>{{small|Painted by Vasily T. Timofeyev (1879)}}]] |

{{ Cytat | {{ Cytat | ||

| − | | <poem>When a branch quivers, brushed, | + | | <poem>When a branch quivers, brushed, |

And part the ash tree’s clusters, and into view flash | And part the ash tree’s clusters, and into view flash | ||

A pair of cheeks than berries more crimson and fair; | A pair of cheeks than berries more crimson and fair; | ||

They are the maid’s who gathers such nuts and fruit there | They are the maid’s who gathers such nuts and fruit there | ||

| − | Into a simple basket, and in which she carries | + | Into a simple basket, and in which she carries |

The cowberries; her lips sparkling as red as the berries; | The cowberries; her lips sparkling as red as the berries; | ||

| − | Alongside steps a youth; he the hazels bends down; | + | Alongside steps a youth; he the hazels bends down; |

The maid catches the nuts then before they touch ground.</poem> | The maid catches the nuts then before they touch ground.</poem> | ||

| − | | źródło = A. Mickiewicz, ''op. cit.'', Book IV, verses 81–88; own paraphrase of M. | + | | źródło = A. Mickiewicz, ''op. cit.'', Book IV, verses 81–88; own paraphrase of M. Weyland’s translation |

| oryg = <poem>Wtem gałąź wstrzęsła się trącona | | oryg = <poem>Wtem gałąź wstrzęsła się trącona | ||

I pomiędzy jarzębin rozsunione grona | I pomiędzy jarzębin rozsunione grona | ||

| Line 363: | Line 363: | ||

}} }} | }} }} | ||

| − | Except that this idealized picture isn’t quite true. There existed a mushroom hierarchy which paralleled the social one: the few choice varieties were reserved for the nobility, while commoners had to content themselves with more or less edible, but certainly less flavourful, species. Mind you, the forest and everything one could find there, belonged to the nobleman. The peasants were usually allowed to obtain certain goods in the lord’s forest, but they had to bring the better species of mushrooms as payment to his estate. One of these species was, without a doubt, the penny bun, which explains why it’s also called | + | Except that this idealized picture isn’t quite true. There existed a mushroom hierarchy which paralleled the social one: the few choice varieties were reserved for the nobility, while commoners had to content themselves with more or less edible, but certainly less flavourful, species. Mind you, the forest and everything one could find there, belonged to the nobleman. The peasants were usually allowed to obtain certain goods in the lord’s forest, but they had to bring the better species of mushrooms as payment to his estate. One of these species was, without a doubt, the penny bun, which explains why it’s also called “king bolete” in English, ''“Herrenpilz”'' (“lord’s mushroom”) in German and ''“borowik szlachetny”'' (“noble mushroom”) in Polish. What other mushrooms did the nobles call dibs on? |

{{ Cytat | {{ Cytat | ||

| Line 382: | Line 382: | ||

This short list is validated by Old Polish recipës, which don’t mention any other mushroom species. It turns out that the range of mushrooms appreciated by the high-born was quite limited. And even that only applied to the more intrepid ones who didn’t listen to the dieticians’ advice to stay away from all of these watery, dirty and certainly unhealthy ([[Good Humour, Good Health|cold and moist in the highest degree]]) or even poisonous toadstools. Probably the oldest Polish recipë for mushrooms is the one given by Maciej Miechowita, the Renaissance-era court physician to King Sigismund I. | This short list is validated by Old Polish recipës, which don’t mention any other mushroom species. It turns out that the range of mushrooms appreciated by the high-born was quite limited. And even that only applied to the more intrepid ones who didn’t listen to the dieticians’ advice to stay away from all of these watery, dirty and certainly unhealthy ([[Good Humour, Good Health|cold and moist in the highest degree]]) or even poisonous toadstools. Probably the oldest Polish recipë for mushrooms is the one given by Maciej Miechowita, the Renaissance-era court physician to King Sigismund I. | ||

| − | [[File:Grzyby za płot.jpg|thumb|King Sigismund | + | [[File:Grzyby za płot.jpg|thumb|King Sigismund I’s court physician’s mushroom recipë]] |

{{ Cytat | {{ Cytat | ||

| Mushrooms, seasoned in the choicest manner, are best when tossed over the fence. No cure exists for their pernicious complexion. | | Mushrooms, seasoned in the choicest manner, are best when tossed over the fence. No cure exists for their pernicious complexion. | ||

| Line 434: | Line 434: | ||

{{ Cytat | {{ Cytat | ||

| − | | The chanterelle mushroom {{...}} is readily used as food in certain places, {{...}} yet it poses a dire hazard, often causing mighty stomach aches and diarrhoea. | + | | The chanterelle mushroom {{...}} is readily used as food in certain places, {{...}} yet it poses a dire hazard, often causing mighty stomach aches and diarrhoea. |

| oryg = Bedłka pieprznik: {{...}} Lubo go w niektórych miejscach na pokarm zażywają, {{...}} wielkie w tym niebezpieczeństwo: częstokroć bowiem czyni wielkie bóle w żołądku i biegunki. | | oryg = Bedłka pieprznik: {{...}} Lubo go w niektórych miejscach na pokarm zażywają, {{...}} wielkie w tym niebezpieczeństwo: częstokroć bowiem czyni wielkie bóle w żołądku i biegunki. | ||

| źródło = {{Cyt | | źródło = {{Cyt | ||

| Line 459: | Line 459: | ||

For their harmfulness, or else their unpleasant flavour; | For their harmfulness, or else their unpleasant flavour; | ||

Yet are not without use, for to beasts they are food, | Yet are not without use, for to beasts they are food, | ||

| − | To the insects a nest, and add charm to the wood. | + | To the insects a nest, and add charm to the wood. |

On the meadow’s green cloth they arise in ranks prim | On the meadow’s green cloth they arise in ranks prim | ||

| − | Like a neat table setting; with smooth rounded rim, | + | Like a neat table setting; with smooth rounded rim, |

'''Brittlegills, silver, yellow and red''', stand in line: | '''Brittlegills, silver, yellow and red''', stand in line: | ||

Perfect row of small goblets with various filled wine; | Perfect row of small goblets with various filled wine; | ||

The '''foxy'''’s upturned tumbler, round-bottomed and plain; | The '''foxy'''’s upturned tumbler, round-bottomed and plain; | ||

| − | '''Horn of plenty''', a flute glass designed for champagne; | + | '''Horn of plenty''', a flute glass designed for champagne; |

'''Milk caps''', rotund and white, broad and flat, smooth as silk: | '''Milk caps''', rotund and white, broad and flat, smooth as silk: | ||

Sets of fine Dresden teacups, all brimful with milk; | Sets of fine Dresden teacups, all brimful with milk; | ||

And the spherical '''puffball''', filled up with black dust | And the spherical '''puffball''', filled up with black dust | ||

| − | Like a pepper pot {{...}}</poem> | + | Like a pepper pot {{...}}</poem> |

| oryg = <poem>Inne pospólstwo grzybów pogardzone w braku | | oryg = <poem>Inne pospólstwo grzybów pogardzone w braku | ||

Dla szkodliwości albo niedobrego smaku; | Dla szkodliwości albo niedobrego smaku; | ||

| Line 484: | Line 484: | ||

I kulista, czarniawym pyłkiem napełniona | I kulista, czarniawym pyłkiem napełniona | ||

'''Purchawka''', jak pieprzniczka {{...}}</poem> | '''Purchawka''', jak pieprzniczka {{...}}</poem> | ||

| − | | źródło = A. Mickiewicz, ''op. cit.'', Book III, verses 270–279; own paraphrase of M. | + | | źródło = A. Mickiewicz, ''op. cit.'', Book III, verses 270–279; own paraphrase of M. Weyland’s translation }} |

| <span style="font-size:92%;"><i><gallery align=right mode=packed heights=105px> | | <span style="font-size:92%;"><i><gallery align=right mode=packed heights=105px> | ||

| − | File:Russula delica.jpg| | + | File:Russula delica.jpg|“Brittlegills, silver…” |

| − | File:Russula claroflava.jpg| | + | File:Russula claroflava.jpg|“… yellow,…” |

| − | File:Russula atropurpurea.jpg| | + | File:Russula atropurpurea.jpg|“… and red,… small goblets with various filled wine” |

| − | File:Leccinum vulpinum.jpg| | + | File:Leccinum vulpinum.jpg|“The foxy’s upturned tumbler” |

| − | File:Craterellus cornucopioides.jpg| | + | File:Craterellus cornucopioides.jpg|“Horn of plenty: a flute glass designed for champagne” |

| − | File:Lactarius piperatus.jpg| | + | File:Lactarius piperatus.jpg|“Milk caps,… fine Dresden teacups, all brimful with milk” |

| − | File:Lycoperdon perlatum.jpg| | + | File:Lycoperdon perlatum.jpg|“Puffball… like a pepper pot” |

</gallery></i></span> | </gallery></i></span> | ||

|}</nomobile><mobileonly>{{ Cytat | |}</nomobile><mobileonly>{{ Cytat | ||

| Line 498: | Line 498: | ||

For their harmfulness, or else their unpleasant flavour; | For their harmfulness, or else their unpleasant flavour; | ||

Yet are not without use, for to beasts they are food, | Yet are not without use, for to beasts they are food, | ||

| − | To the insects a nest, and add charm to the wood. | + | To the insects a nest, and add charm to the wood. |

On the meadow’s green cloth they arise in ranks prim | On the meadow’s green cloth they arise in ranks prim | ||

| − | Like a neat table setting; with smooth rounded rim, | + | Like a neat table setting; with smooth rounded rim, |

'''Brittlegills, silver, yellow and red''', stand in line: | '''Brittlegills, silver, yellow and red''', stand in line: | ||

Perfect row of small goblets with various filled wine; | Perfect row of small goblets with various filled wine; | ||

The '''foxy'''’s upturned tumbler, round-bottomed and plain; | The '''foxy'''’s upturned tumbler, round-bottomed and plain; | ||

| − | '''Horn of plenty''', a flute glass designed for champagne; | + | '''Horn of plenty''', a flute glass designed for champagne; |

'''Milk caps''', rotund and white, broad and flat, smooth as silk: | '''Milk caps''', rotund and white, broad and flat, smooth as silk: | ||

Sets of fine Dresden teacups, all brimful with milk; | Sets of fine Dresden teacups, all brimful with milk; | ||

And the spherical '''puffball''', filled up with black dust | And the spherical '''puffball''', filled up with black dust | ||

| − | Like a pepper pot {{...}}</poem> | + | Like a pepper pot {{...}}</poem> |

| oryg = <poem>Inne pospólstwo grzybów pogardzone w braku | | oryg = <poem>Inne pospólstwo grzybów pogardzone w braku | ||

Dla szkodliwości albo niedobrego smaku; | Dla szkodliwości albo niedobrego smaku; | ||

| Line 523: | Line 523: | ||

I kulista, czarniawym pyłkiem napełniona | I kulista, czarniawym pyłkiem napełniona | ||

'''Purchawka''', jak pieprzniczka {{...}}</poem> | '''Purchawka''', jak pieprzniczka {{...}}</poem> | ||

| − | | źródło = A. Mickiewicz, ''op. cit.'', Book III, verses 270–279; own paraphrase of M. | + | | źródło = A. Mickiewicz, ''op. cit.'', Book III, verses 270–279; own paraphrase of M. Weyland’s translation }} |

<span style="font-size:92%;"><i><gallery align=right mode=packed heights=105px> | <span style="font-size:92%;"><i><gallery align=right mode=packed heights=105px> | ||

| − | File:Russula delica.jpg| | + | File:Russula delica.jpg|“Brittlegills, silver…” |

| − | File:Russula claroflava.jpg| | + | File:Russula claroflava.jpg|“… yellow,…” |

| − | File:Russula atropurpurea.jpg| | + | File:Russula atropurpurea.jpg|“… and red,… small goblets with various filled wine” |

| − | File:Leccinum vulpinum.jpg| | + | File:Leccinum vulpinum.jpg|“The foxy’s upturned tumbler” |

| − | File:Craterellus cornucopioides.jpg| | + | File:Craterellus cornucopioides.jpg|“Horn of plenty: a flute glass designed for champagne” |

| − | File:Lactarius piperatus.jpg| | + | File:Lactarius piperatus.jpg|“Milk caps,… fine Dresden teacups, all brimful with milk” |

| − | File:Lycoperdon perlatum.jpg| | + | File:Lycoperdon perlatum.jpg|“Puffball… like a pepper pot” |

</gallery></i></span></mobileonly> | </gallery></i></span></mobileonly> | ||

| − | We’ve got here, again, various species of brittlegills; judging by the colours, they may be the '''milk-white brittlegill''' (''Russula delica''), '''yellow swamp brittlegill''' (''Russula claroflava'') and '''purple brittlegill''' (''Russula atropurpurea''). The '''foxy bolete''' (''Leccinum scabrum''), which the poet likened to the ''kulawka'', an Old Polish round-bottomed party glass whose contents you have to quaff in a single gulp before you lay it back on the table, is known in Polish as '' | + | We’ve got here, again, various species of brittlegills; judging by the colours, they may be the '''milk-white brittlegill''' (''Russula delica''), '''yellow swamp brittlegill''' (''Russula claroflava'') and '''purple brittlegill''' (''Russula atropurpurea''). The '''foxy bolete''' (''Leccinum scabrum''), which the poet likened to the ''kulawka'', an Old Polish round-bottomed party glass whose contents you have to quaff in a single gulp before you lay it back on the table, is known in Polish as ''“koźlarz sosnowy”'', or “pine billy goat”. The '''horn of plenty''' (''Craterellus cornucopioides''), also known as “black trumpet” or “trumpet of death” (despite being edible), has a relatively unassuming Polish name: ''“lejkowiec”'', which means “funnel mushroom”. The '''peppery milk cap''' (''Lactarius piperatus'') gets its appellation from its acrid taste and milk-white colour. |

| − | <nomobile>[[File:Muchomór.jpg|thumb|left|upright=.6|'' | + | <nomobile>[[File:Muchomór.jpg|thumb|left|upright=.6|''“{{...}} Will, angry, with his foot break it off or demolish; defacing thus the sward, does a thing very foolish.”''<ref>''Ibid.'', Book III, verses 287–289</ref>]]</nomobile> |

The beautifully descriptive similë, comparing toadstools to drinkware, brings us to the topic of Old Polish beverages. But let’s leave the subject of what was drunk at Soplicowo for another post. Meanwhile, let me end this post by quoting Mickiewicz’s admonition about how to deal with inedible mushrooms, which is as valid today as it was two centuries ago. | The beautifully descriptive similë, comparing toadstools to drinkware, brings us to the topic of Old Polish beverages. But let’s leave the subject of what was drunk at Soplicowo for another post. Meanwhile, let me end this post by quoting Mickiewicz’s admonition about how to deal with inedible mushrooms, which is as valid today as it was two centuries ago. | ||

| Line 543: | Line 543: | ||

He who stoops such to pick, when his error is plain, | He who stoops such to pick, when his error is plain, | ||

Will, angry, with his foot break it off or demolish; | Will, angry, with his foot break it off or demolish; | ||

| − | Defacing thus the sward, does a thing very foolish.</poem> | + | Defacing thus the sward, does a thing very foolish.</poem> |

| oryg = <poem>Ni wilczych, ni zajęczych nikt dotknąć nie raczy, | | oryg = <poem>Ni wilczych, ni zajęczych nikt dotknąć nie raczy, | ||

A kto schyla się ku nim, gdy błąd swój obaczy, | A kto schyla się ku nim, gdy błąd swój obaczy, | ||

| Line 550: | Line 550: | ||

| źródło = A. Mickiewicz, ''op. cit.'', Book III, verses 286–289 | | źródło = A. Mickiewicz, ''op. cit.'', Book III, verses 286–289 | ||

}} | }} | ||

| − | <mobileonly>[[File:Muchomór.jpg|thumb|upright=.6|'' | + | <mobileonly>[[File:Muchomór.jpg|thumb|upright=.6|''“{{...}} Will, angry, with his foot break it off or demolish; defacing thus the sward, does a thing very foolish.”''<ref>''Ibid.'', Book III, verses 287–289</ref>]]</mobileonly> |

{{clear}} | {{clear}} | ||

{{Przypisy}} | {{Przypisy}} | ||

Revision as of 16:34, 11 May 2024

Epic Cooking Food and Drink in “Pan Tadeusz”, the Polish National Epic |

Epic Cooking

Food and Drink in “Pan Tadeusz”,

the Polish National Epic

Have you been mushroom picking this year yet? If you’re Polish, then your answer is likely yes. In Poland, gathering wild mushrooms in a forest is something of a national pastime. As reported by a polling agency, more than three quarters of Poles have engaged in this activity at least once in their lifetime, and more than two fifths do it on a regular basis.[1] According to a classification scheme proposed over half a century ago by Mr. and Mrs. Wasson, who wrote a book on the role of mushrooms in the history and culture of Russia and the world,[2] the Poles, along with other Balto-Slavic nations and northern Italians, belong to mycophillic, or mushroom-loving, peoples. On the other end of the spectrum are mycophobic nations, which in Europe are mostly concentrated in the North Sea basin and whose risk acceptance in regards to mushroom picking only goes as far as picking up a plastic box of cultivated champignons in a supermarket.

Mycophobes may find the Polish passion for gathering, preserving and consuming wild mushrooms shockingly adventurous, foolhardy even. Isn’t it dangerous? Well, yes, mushroom poisoning does occur more often in Poland than it does in countries where mushroom picking simply isn’t a thing. But hardly as common as you might think. Within five years from 2009 to 2013, only eight people in western and central Poland died from mushroom poisoning (compared to 112 people who died from various alcohols, including 49 from methanol, and 95 who died from pharmaceutical drug overdose).[3]

Mushroom picking is a family pastime, so Polish and other mycophiles typically learn to tell edible mushrooms from inedible and poisonous ones at an early age. Until 1999, a lesson on mushroom species was part of Poland’s elementary school curriculum.[4] Many field guides – printed and online – are available too. But most Polish mushroomers learn to recognise fungal species from their parents or grandparents, and continue to gather the same few kinds of mushrooms (even though many more are edible too) which they learned to pick when they were children. Field guides do little to expand their preferences; they only seem to unify mushroom names used throughout the country.[5]

Painted by Ivan L. Gorokhov (1912)

So which mushrooms are most commonly picked in Poland?

- The king bolete (Boletus edulis), also known as “penny bun”, “cep” or “porcino”, reigns supreme. In Polish, it’s known as “borowik szlachetny” (literally, “noble pine-forest mushroom”) or “prawdziwek” (“true mushroom”).

- The bay bolete (Imleria badia) is related, but less prized. Its second-best status is reflected in its Polish name, “podgrzybek”, which may be translated as “deputy mushroom” or “junior mushroom”. It’s popular enough in Poland that the Russians call it “polskiy grib”, or “Polish mushroom”.

- The golden chanterelle (Cantharellus cibarius), a bright-yellow trumpet-shaped mushroom with a slightly peppery flavour, called “kurka” (“little chick”) or “pieprznik” (“pepper mushroom”) in Polish, comes last on the podium. Mickiewicz referred to it as “lisica”, or “vixen”.

Further spots are taken by:

- various species of slippery jacks (genus Suillus), which the Poles refer to as “maślaki” (“butterballs”) because of their slimy caps;

- saffron milk cap (Lactarius deliciosus), a red-brownish mushroom which oozes a milky liquid when damaged; its Polish name is “rydz”, or “ginger-coloured mushroom”;

- parasol mushroom (Macrolepiota procera), or “kania” in Polish, whose broad flat cap may be fried in bread crumbs like a pork cutlet;

- honey mushroom (Armillaria mellea), small and sweetish, which grows in patches on tree stumps; its Polish name is “opieńka miodowa”, or “honey stumper”;

- some species of knight caps (genus Tricholoma), known in Polish as “gąski”, or “little geese”.

Mushroom season lasts from late summer to mid-autumn, but Polish people preserve most of the fungi they collect, so that they can enjoy them all year long. This they do mostly by drying and to a lesser extent by pickling in vinegar (mostly in the case of slippery jacks and other species which don’t lend themselves to drying) or, less traditionally, freezing. The Poles typically gather mushrooms for their own use, but they face competition from professional gatherers who, though less numerous (only 1% of all mushroomers), pick much larger quantities than recreational mushroom hunters do.[1]

This is the situation today. And what was it like in the past? “Mushrooming’s ancient and decorous rite” is described with great beauty in Pan Tadeusz, the Polish national epic written by Adam Mickiewicz (pronounced meets·kyeh·veetch) in 1834. So let’s pay yet another visit to the fictional manor of Soplicowo (saw·plee·tsaw·vaw) and see what kinds of mushrooms the epic’s characters gathered and what use they later put them to.

“There Were Mushrooms Aplenty”

Painted by Franciszek Kostrzewski (ca. 1860)

A small grove, sparsely wooded, now came into sight; | ||||||

| — Adam Mickiewicz: Pan Tadeusz, or The Last Foray in Lithuania: A Tale of the Gentry during 1811-1812, translated by Marcel Weyland, Book III, verses 220–236 * The action takes place in early September (of 1811), at the height of mushroom season. The Polish adjective “majowych”, here mistranslated as “of May”, was actually used by Mickiewicz in the now largely forgotten sense of “vividly green”.

Original text:

|

The whole affair began when Lady Telimena, bored by the men’s heated argument about hare hunting at breakfast, declared that she was going out to gather saffron milk caps, then took Lord Chamberlain’s youngest daughter by the hand and left. Judge Soplica saw this as an opportunity to calm his guests down and announced a mushroom-picking competition:

“It is mushroom time, sirs, in the wood! | ||||

— A. Mickiewicz, op. cit., Book II, verses 846–850; own paraphrase of M. Weyland’s translation

Original text:

|

As we can already see at the very start, the most sought-after mushroom in Soplicowo was not the king bolete, but the saffron milk cap. But that’s not to mean that all other mushrooms were overlooked by the Judge’s guests. I remember the impression I had long ago, when I was reading Pan Tadeusz for the first time, that part of Book III was a veritable mushroom field guide in verse. So let’s see what species the poet mentioned in his epic:

There were mushrooms aplenty: the lads chanterelles gather, | ||||

— A. Mickiewicz, op. cit., Book III, verses 260–269; own paraphrase of M. Weyland’s translation

Original text:

|

Only three edible species? That’s not as many I thought. But a few hundred verses further, in a passage about the mushroom hunters coming home with their trophies, we can spot two more:

From the grove comes | ||||

— A. Mickiewicz, op. cit., Book III, verses 691–698; own paraphrase of M. Weyland’s translation

Original text:

|

All in all, there are five edible kinds of mushrooms (the fly agaric, here translated as “fly-bane”, is poisonous). The one we haven’t discussed yet is the brittlegill, which in fact refers to several species of the genus Russula. Mickiewicz calls them by the word “surojadki” (“eaten raw”), but the Polish term that is more common today is “gołąbki”, or “little pigeons”. They’re edible, but often ignored nowadays, as their taste is just okay and, having gills rather than pores on the underside of the cap, they can be confused with some toxic species.

Mushroom War

A small digression before we move on: what is this song which calls the king bolete “the colonel of mushrooms”? According to the poet’s explanatory note, it’s “a folk song well known in Lithuania about mushrooms marching to war under a king bolete’s command. This song describes the characteristics of edible mushrooms.”[8] Why did the author of a Polish epic draw inspiration from Lithuanian folklore? Because the Grand Duchy of Lithuania is where the story is set; in fact, the epic’s very first words are “Lithuania, my country”.[9] In the poet’s time, the Grand Duchy was a part of the Russian Empire that was inhabited by Polish-speaking nobility (which he belonged to himself), Belarusian or Lithuanian-speaking peasants and Yiddish-speaking Jews.

Anyway, Mickiewicz didn’t quote the song directly. But, as luck would have it, Mickiewiczologists were able to track down, more than a hundred years ago, its original Lithuanian-language lyrics. Here it goes, as noted down by Mr. and Mrs. Angrabaitis in what is now Lithuania’s Marijampolė County:

What did the little hare say when running through the wood? | ||||

— Lithuanian folk song as quoted in: Stanisław Windakiewicz: Prolegomena do „Pana Tadeusza”, Kraków: Gebethner i Wolff, 1918, p. 227–228, own translation

Original text:

|

As you can see, apart from the species mentioned in Pan Tadeusz, such as saffron milk caps, king boletes and stumpers (honey mushrooms), the song also mentioned other edible, if less prized, mushrooms: the red-capped scaber stalk (Leccinum aurantiacum) and the slippery jack. It could also be that the Lithuanian word “zuikužėlis” refers, in this case, not to a hare running around the forest, but to any of the mushrooms whose Lithuanian folk names derive from the word for “bunny”. These include the quite edible birch bolete (Leccinum scabrum) and the very inedible bitter bolete (Tylopilus felleus; this one is also known as “zajączek gorzki”, or “bitter bunny”, in Polish).[10] In any case, it’s quite possible that in Mickiewicz’s time the song had more verses and served as a real oral field guide to be sung while picking mushrooms.

While we’re digressing, let’s clarify one more thing: why did the Tribune gather fly agarics, the most recognizable of toxic toadstools? Was it just to show his contempt for any forest activity that didn’t involve hunting big game, the only pastime he thought becoming of a nobleman? Or did he intend to poison somebody? Or something. As we already know, the Tribune absolutely hated flies. And the fly agaric (Amanita muscaria), as both its English and Polish names imply (Polish “muchomor” literally means “fly-bane”), was used as insecticide for centuries. This is how:

| Dice a fresh fly agaric and cook it in boiling milk. Then pour the milk into cups for the flies [to drink] or smear it in the gaps where bedbugs are. | ||||

— Feliks Berdan: Muchomór, in: Encyklopedyja Powszechna, vol. XIX, Warszawa: S. Orgelbrand, 1865, p. 15, own translation

Original text:

|

Recipës

Painted by Tomasz Łosik (1883)

In the end, a bell called the mushroom hunters back to the manor for lunch. Even though originally the hunt had been Telimena’s idea, she must have been, as the Notary observed, looking for mushrooms in the trees, as she returned empty-handed from the wood. So did her two suitors, Thaddeus and the Count. We don’t know who won the Judge’s competition. Nor does the poem mention what happened with the mushrooms others had collected. We can only guess.

Anyone who has been to a mushroom hunt knows that after the fun part, which is the picking itself, you still have to sort, clean and dice the mushrooms, discard the wormy ones and decide which specimens are to be eaten right away and which are suitable for drying or pickling. Without a doubt the nobles delegated these thankless tasks to the servants, before settling down for lunch which the same servants had prepared.

Eventually, the mushrooms must have ended up on the nobles’ table. But in what form? The poet didn’t say; there is no mention of any mushroom-containing dishes anywhere in Pan Tadeusz. But that shouldn’t stop us from speculating about what mushroom dishes they could have enjoyed – based on cook books from the same period.

Let’s start with the saffron milk caps, which Mickiewicz considered to “have the best taste”. His friend, Karolina Nakwaska, who wrote a home-making book for women, gave a recipë that is perfect in its simplicity.

| Take carefully selected, worm-free saffron milk caps, remove the stems; if the caps are too big, then cut them in half. Arrange on a grill over a slow fire, place a small piece of butter in each cap, sprinkle with pepper and salt, and fry without flipping them over. You can use very good olive oil instead of butter. Add chopped parsley and onion. Serve after ten minutes. Saffron milk caps and [other] mushrooms fried simply in butter with onion, pepper and salt, are just perfect. | ||||

— Karolina Nakwaska: Dwór wiejski, vol. II, Lipsk: Księgarnia Michelsena, 1858, p. 199, own translation

Original text:

|

As for king boletes, Jan Szyttler advised to use them as a filling for little aromatic yeast pies. This is what he wrote in his cookbook, published a year before Pan Tadeusz:

| Cook some fresh king boletes in boiling water, then fry them with onion (as you normally would) and a small piece of dried bouillon; once fried, chop them up as finely as possible. Add four eggs, nutmeg and pepper. Roll out hard-kneaded yeast dough, then fill with the mushrooms as for kołdunki [i.e., pierogi, or filled dumplings], fry in fat until brown and serve hot. | ||||

— Jan Szyttler: Kucharz dobrze usposobiony, vol. I, Wilno: R. Daien, 1833, p. 52–53, own translation

Original text:

|

And what about the chanterelles, so praised in Lithuanian folk songs? Well, nothing! I haven’t found any recipës that would refer to this species of mushroom from before the 20th century. It looks like chanterelles weren’t as popular in Mickiewicz’s time as he made it seem. Or at least not in all circles.

Fungal Commoners

Hunter-gatherer cultures typically divide their labour along gender and age lines: men hunt, while women and children gather.[12] In farming societies, where foraging is no longer the chief source of food, but still helps expand the menu, this division is not only continued, but also expanded to include a class dimension: hunting, treated increasingly as a sport, is the domain of noblemen, while picking berries, nuts and herbs is left to peasants, especially women. In Pan Tadeusz, we can observe a pair of young peasants – a girl and a boy – collecting cowberries and hazelnuts.

Painted by Vasily T. Timofeyev (1879)

When a branch quivers, brushed, | ||||

— A. Mickiewicz, op. cit., Book IV, verses 81–88; own paraphrase of M. Weyland’s translation

Original text:

|

In this hierarchy of forest activities, mushroom picking was somewhere near the middle. Berry shrubs grow in vast patches, each identical to the next; a good mushroom, on the other hand, is hard to find and no two fungi are the same. So while regular gathering is a tedious, back-breaking chore, mushroom picking can be seen as a challenging or even competitive pastime. There’s a reason why it’s often called mushroom hunting. Fungi may lack claws or fangs, but the risk of poisoning adds a certain dose of excitement.

Just like recreational mushroom hunters today have to share the forest with professionals, so was mushroom picking in times of yore practised both by peasants – for whom it was a way to supplement their meagre diet – and by the nobility, who saw it as a more democratic alternative to big-game hunting. Note how, in Soplicowo, only the nobles engaged in the mushroom hunt, yet the party was still more inclusive (from the Chamberlain’s little daughter to the old Tribune) than at the bear hunt, which was a men-only affair.

Mushrooms are often considered one of the few foodstuffs used in Old Polish cuisine which crossed class boundaries and could be found on both peasant and lordly tables.

| Whereas nobility feasted on choice meats, rich cakes, and imported wines, the peasantry had to make do with groats, dumplings, cabbage, and coarse breads. Mushrooms were the great equalizer. They had a place of honor on the banquet tables of royalty, but were equally at home in the humble peasant cottage. |

| — Robert Strybel, Maria Strybel: Polish Heritage Cookery, New York: Hippocrene Books, 1993, p. 396 |

Except that this idealized picture isn’t quite true. There existed a mushroom hierarchy which paralleled the social one: the few choice varieties were reserved for the nobility, while commoners had to content themselves with more or less edible, but certainly less flavourful, species. Mind you, the forest and everything one could find there, belonged to the nobleman. The peasants were usually allowed to obtain certain goods in the lord’s forest, but they had to bring the better species of mushrooms as payment to his estate. One of these species was, without a doubt, the penny bun, which explains why it’s also called “king bolete” in English, “Herrenpilz” (“lord’s mushroom”) in German and “borowik szlachetny” (“noble mushroom”) in Polish. What other mushrooms did the nobles call dibs on?

| Of all mushrooms, the rich only knew king boletes, saffron milk caps, morels, champignons and truffles. | ||||

— Łukasz Gołębiowski: Domy i dwory, vol. IV, Warszawa: self-published, 1830, p. 47, own translation

Original text:

|

This short list is validated by Old Polish recipës, which don’t mention any other mushroom species. It turns out that the range of mushrooms appreciated by the high-born was quite limited. And even that only applied to the more intrepid ones who didn’t listen to the dieticians’ advice to stay away from all of these watery, dirty and certainly unhealthy (cold and moist in the highest degree) or even poisonous toadstools. Probably the oldest Polish recipë for mushrooms is the one given by Maciej Miechowita, the Renaissance-era court physician to King Sigismund I.

| Mushrooms, seasoned in the choicest manner, are best when tossed over the fence. No cure exists for their pernicious complexion. | ||||

— Maciej Miechowita, quoted in: Marcin z Urzędowa: Herbarz polski, to jest o przyrodzeniu ziół i drzew rozmaitych, i innych rzeczy do lekarstw należących, Kraków: Drukarnia Łazarzowa, 1595, p. [149], own translation

Original text:

|

The opinion which the Polish Enlightenment-era poet and publicist Stanisław Trembecki held of mushrooms wasn’t much better.

| Forest mushrooms arise from mould growing on rotting deadwood and pushing up from beneath the ground to structure itself on the surface! More than half of mushrooms constitute virulent poison, while other are less noxious and known as such. […] Every year, papers report entire houses extinct from mushroom consumption. Have mushrooms ever made anyone feel better? I forgive the pauper who, desperate for food, may risk any haphazard fare, but the well-to-do cannot be excused for devouring such filth out of perverted luxury. | ||||

— Stanisław Trembecki: Pokarmy, in: Pisma wszystkie, vol. 2, Warszawa: 1953, p. 206; quoted in: Grażyna Szelągowska: Grzyby w polskiej tradycji kulinarnej, in: Studia i Materiały Ośrodka Kultury Leśnej, 16, Ośrodek Kultury Leśnej w Gołuchowie, 2017, p. 214, own translation

Original text:

|

All this meant that the peasants were still left with quite a wide range of perfectly edible mushrooms which the nobles shunned in disgust.

| The yokel’s fare has always consisted of […] sundry mushrooms, such as brittlegills, […] tacked, fleecy and woolly milk caps, chanterelles, sooty heads, milk whites, stumpers, yellow knights, scaber stalks, butterballs; and in this abundance mistaking the poisonous ones for the good, he often pays with his health or even life. | ||||

— Ł. Gołębiowski, op. cit., s. 31–32, own translation

Original text:

|

As you can see, there was a time when chanterelles, so highly prized today, were treated with the same suspicion and contempt as all other peasant food. Some even thought them outright toxic.

| The chanterelle mushroom […] is readily used as food in certain places, […] yet it poses a dire hazard, often causing mighty stomach aches and diarrhoea. | ||||

— Krzysztof Kluk: Dykcyonarz roślinny, vol. I, Warszawa: Drukarnia Xięży Pijarów, 1805, p. 12–13, own translation

Original text:

|

It seems that it was only Mickiewicz, so fascinated by peasant culture, who had the nobles of Soplicowo forage for the mushroom plebs which, in real life, they wouldn’t even deign to look at.

Overlooked and Looked Down On

And then, there are the mushroom species which even the unfussy Soplicas didn’t pick. They’re all edible, but only so-so flavourwise. And yet, Mickiewicz devoted to them no less space in his epic than to those which ended up in the wicker baskets.

|

Other, more common, mushrooms did not win their favour | ||||

— A. Mickiewicz, op. cit., Book III, verses 270–279; own paraphrase of M. Weyland’s translation

Original text:

|

We’ve got here, again, various species of brittlegills; judging by the colours, they may be the milk-white brittlegill (Russula delica), yellow swamp brittlegill (Russula claroflava) and purple brittlegill (Russula atropurpurea). The foxy bolete (Leccinum scabrum), which the poet likened to the kulawka, an Old Polish round-bottomed party glass whose contents you have to quaff in a single gulp before you lay it back on the table, is known in Polish as “koźlarz sosnowy”, or “pine billy goat”. The horn of plenty (Craterellus cornucopioides), also known as “black trumpet” or “trumpet of death” (despite being edible), has a relatively unassuming Polish name: “lejkowiec”, which means “funnel mushroom”. The peppery milk cap (Lactarius piperatus) gets its appellation from its acrid taste and milk-white colour.

The beautifully descriptive similë, comparing toadstools to drinkware, brings us to the topic of Old Polish beverages. But let’s leave the subject of what was drunk at Soplicowo for another post. Meanwhile, let me end this post by quoting Mickiewicz’s admonition about how to deal with inedible mushrooms, which is as valid today as it was two centuries ago.

None those hares’ or wolves’ mushrooms to gather would deign, | ||||

— A. Mickiewicz, op. cit., Book III, verses 286–289

Original text:

|

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Marcin Herrmann: Uroczysty obrzęd grzybobrania, No. 143/2018, Warszawa: Centrum Badania Opinii Społecznej, October 2018

- ↑ Valentina Pavlovna Wasson, R. Gordon Wasson: Mushrooms, Russia and History, vol. 1, New York: Panthon Books, 1957, p. XVII

- ↑ As reported by six out of Poland’s ten toxicological centres. Anna Krakowiak et al.: Poisoning Deaths in Poland: Types and Frequencies Reported in Łódź, Kraków, Sosnowiec, Gdańsk, Wrocław and Poznań During 2009–2013, in: International Journal of Occupational Medicine and Environmental Health, 30 (6), 2017, p. 903

- ↑ Łukasz Łuczaj: Collecting and Learning to Identify Edible Fungi in Southeastern Poland: Age and Gender Differences, in: Ecology of Food and Nutrition, 50:4, Routledge, 2011, p. 321

- ↑ Ibid., p. 332

- ↑ Adam Mickiewicz: Pan Tadeusz, or The Last Foray in Lithuania: A Tale of the Gentry during 1811-1812, translated by Marcel Weyland, Book III, verses 691–694

- ↑ Ibid., Book III, verses 245–246

- ↑ Ibid., explanatory notes; own translation

- ↑ Ibid., Book I, verse 1

- ↑ Jūratė Lubienė: Žvėrių pavadinimai lietuvių kalbos mikonimų motyvacijos sistemoje, in: Res Humanitariae, Klaipėdos universitetas, 2014, p. 108

- ↑ A. Mickiewicz, op. cit., Book III, verses 698–699

- ↑ Recent archaeological and ethnographic research has called this assertion into question (note added on 7 July 2023). Source: Abigail Anderson, Sophia Chilczuk, Kaylie Nelson, Roxanne Ruther, Cara Wall-Scheffler: The Myth of Man the Hunter: Women’s contribution to the hunt across ethnographic contexts, in: PLoS ONE, 18 (6), Public Library of Science, 28 June 2023

- ↑ Ibid., Book IV, verses 83–84

- ↑ Ibid., Book III, verses 287–289

- ↑ Ibid., Book III, verses 287–289

Bibliography

- Andrzej Grzywacz: Tradycje zbiorów grzybów leśnych w Polsce, in: Studia i Materiały CEPL w Rogowie, 44/3, Centrum Edukacji Przyrodniczo-Leśnej w Rogowie, 2015, p. 189–199

- Internetinis grybų katalogas

- Marcin Kotowski: History of mushroom consumption and its impact on traditional view on mycobiota: an example from Poland, in: Microbial Biosystems, 4 (3), December 2009, p. 1–13

- Łukasz Łuczaj: Collecting and Learning to Identify Edible Fungi in Southeastern Poland: Age and Gender Differences, in: Ecology of Food and Nutrition, 50:4, Routledge, 2011, p. 319–336

- Grażyna Szelągowska: Grzyby w polskiej tradycji kulinarnej, in: Studia i Materiały Ośrodka Kultury Leśnej, 16, Ośrodek Kultury Leśnej w Gołuchowie, 2017, p. 213–225

| ◀️ Previous | 📜 List of posts | Next ▶️ |

| ⏮️ First | 🎲 Random post | Latest ⏭️ |