Holey Breads

OK, so this post isn't about holy breads – as in the Eucharist. It's about breads with holes. And I don't mean little pockets of air as in sourdough bread. I mean breads that are shaped like rings, wreaths or knots, with the dough surrounding one or more holes. You know, bagels, pretzels and the like.

In a few shopping malls and other places in Warsaw you can find stands like the one pictured here, selling what the sign claims to be krakowskie precle, or "Cracow pretzels". Intriguingly, the company that distributes them in Warsaw proudly boats that these "pretzels" are shipped each morning straight from Mr. Czaja's bakery in Cracow. But if we take a look at Mr. Grzegorz Czaja's bakery website, we'll see that what he bakes there is not pretzels, but something called obwarzanki (pronounced awb-vah-ZHAHN-kee). It seems as though the obwarzanki magically turn into pretzels the moment they arrive in Warsaw! Can we chalk it up to merely yet another linguistic difference between Cracovian and Warsovian Polish? Or is there a more profound distinction between pretzels and obwarzanki?

"Pretzels, "bagels" and "obwarzanki" are all used by both tourists and native Cracovians to refer to the specifically Cracovian bread which "takes the form of an oval with a hole in the middle" and whose "surface is formed by strands of dough twisted into a spiral".[1] Although unique to Cracow, it nonetheless belongs to the great diverse family of holey breads. So let's take a look at the bigger picture now.

Common Ancestors

Bagels, pretzels and obwarzanki are similar enough to each other to suggest a common origin. According to Ms. Maria Balinska, who wrote a book on the history of bagels, holey breads date back all the way to ancient Rome. She believes that all such bread products descend from the buccellata,[2] or small, round, jaw-breaking double-baked biscuits used as army hardtack by Roman legionaries at least as early as the 4th century CE. Whether they were actually ring or rather disc-shaped is uncertain. The author of Pass the Garum, a blog about ancient Roman foodways, reconstructed them as the latter, with only little holes punched with a needle to let air and steam escape during baking. Another hypothesis, also mentioned by Ms. Balinska, says that the buccellatum was the ancestor of the round communion wafer used by Christians in the sacrament of the Eucharist.

Another bread with a long history, which, this time for sure, is made in the shape of elongated rings, is the Middle Eastern ka'ak. These breads are get a mention in the Talmud,[3] so they must have been known at least as eary as the 6th century CE. Unlike the overly simple buccellatum, made only of flour, salt and butter, ka'ak are made from leavened dough. What's interesting is that the leavening agent used here is not yeast, but fermented chickpea.[4] Generously sprinkled with sesame seeds before baking, ka'ak may be still purchased in the streets of Arab and Israeli cities.

Let's go back the Apennine Peninsula. It was in the port town of Puglia (pronounced POOL-yah) in what is now southern Italy that taralli were being boiled and baked as early as the 14th century. That's right, it's a kind of bread that is first boiled and only then baked. Why? Because when the starch on the surface of the dough comes into contact with boiling water, it gets gelatinized,giving the tarallo its shiny and crunchy crust. The stiffened crust also prevents the dough from rising further during baking, which helps keep the bread in shape. And this, in turn, means that you can make bigger ring-shaped breads than you could without boiling them first.[5] Clever, huh?

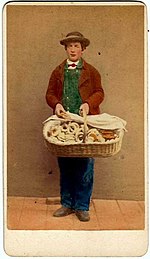

Great, but what's the deal with the ring shape in the first place? Why not a ball or a disc, but a torus, which takes a great a lot more skill to form? Well, this shape has two advantages. First, a holey bread has only a slightly smaller volume with a much larger surface than a whole bread of comparable size (the proof by calculating the surface areas and volumes of a torus and an ellipsoid is left as an exercise for the Reader). And a larger surface area allows the heat to spread more evenly inside the dough during the thermal treatment (boiling or baking). Secondly, a holey bread is easier to transport, especially for a street vendor who can just put his (somehow it's usually been men) taralli on a string or a stick and peddle them in the street. And the customers could even wear their tarallo like a bracelet, if they didn't eat it right away.

Dry taralli were used in a similar way as the ancient buccellata in that they could be stored for up to half a year and then eaten after being dunked in wine for softening. Were these toroidal taralli inspired by the Arab ka'ak, brought by Levantine sailors to the port of Puglia? Quite possibly, but we don't know that for sure. Whatever the case, soon after the taralli had appeared in southern Italy, similar breads were being made in the north. They bore a plethora of regional names, including "bricuocoli", "ciaramilie", "pane del marinaio", "mescuotte", "ciambelle", "ciambelloni", "braciatelle", "brazzatelle" and "brasadèle"[6] (the latter three are reminiscent of "braccialetto", the Italian word for "bracelet"; ultimately, both "braciatella" and "braccialetto" derive from Latin "bracchium", meaning "arm").

Pretzels

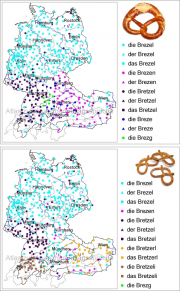

The Italian "la brazzatella" sounds quite similar to the German "die Brezel"… Or is it "des Brezel"? Or "der Brezel"? German speakers can't agree as to the grammatical gender of their pretzels. The jury is also out on whether the first "e" in this word is long or short (as in "der/die/das Bretzel"). There are also those, mostly in Bavaria and Austria, who call it "die Brezen" (or "der Brezen"). Or even "die Brezg", as they say along the Bavarian-Swabian border.[7] What they all do agree on is the pretzel's shape. Not a ring, not a wreath, but a knot which looks like two sixes conjoined at their bellies, with not one, but three holes.

The pretzel's grammatical gender is also an important issue in France, allowing Alsatians to tell an authentic Alsatian pretzel from a fake non-Alsatian one. Or so at least claims one Alsatian blogger:

| "Le bretzel" is this little unspeakable, incongruous and indigestible thing sold by packets in the supermarkets across the Vosges. "La bretzel" is a succulent Alsatian speciality. | ||||

— PiP, vélodidacte: L’histoire de la Bretzel selon l’Hortus Deliciarum, in: Autour du Mont-Sainte-Odile, Overblog, 2013, own translation

Original text:

|

The same blogger proves that pretzels have been known in Alsace since at least the 13th century, because you can find their images in Hortus Deliciarum (Garden of Delights), a kind of medieval illustrated encyclopedia. It was created by Herrad of Landsberg, an abbess of the convent on Mount Saint Odile in the eastern Vosges. You can see breads twisted into the unmistakable pretzel shape in three illuminations depicting Biblical figures seated at a table. What's interesting is that in all three pictures the pretzels lie right next to fish.

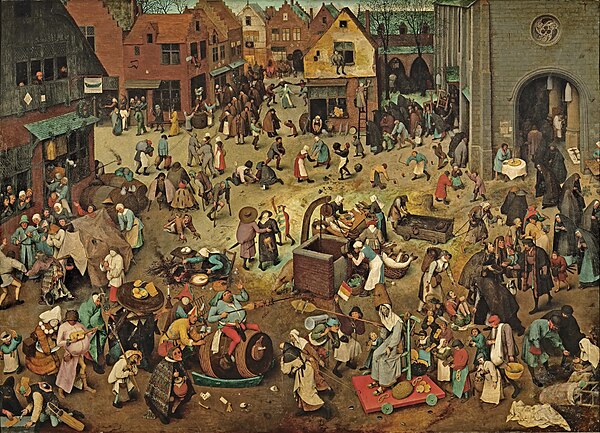

What might pretzels have to do with fish? Well, neither of them contains any ingredients of land-animal origin (pretzel dough contains no eggs or butter), which means they may be safely consumed during a period of Catholic fast. Along with fish, the pretzel used to be one of the chief symbols of Lent, which is best illustrated by Pieter Brueghel's famous painting, The Fight Between Carnival and Lent.

And because pretzels were made from the relatively expensive wheat flour, they were not only a lean product, but also a luxurious one. Some of those who could afford them couldn't even wait until Lent and would start eating them already in the carnival. And so in some parts of Germany and the Low Countries has the pretzel become a traditional carnival treat. In many towns pretzels are given away during carnival parades. The Flemish town of Geraardsbergen is still known for its tradition of throwing little pretzel-shaped sugar-covered cookies called krakelingen into the crowd on the first Monday of March.[8]

But where does this shape come from anyway? Nobody seems to know for sure; even the legends don't agree. One says that the shape of the pretzel is designed to resemble the arms of a monk folded in prayer. According to another one, it was invented by a baker from Württemberg who had been sentenced to death, but whom Count Eberhard von Urach promised to pardon on the condition that he bakes a bread through which the sun would shine three times. In any case, the pretzel shape is so distinctive that bakers' guilds throughout central Europe would adopt it as their coats of arms. You can still find it on the shop sign of many a German bakery. The are differences in the pretzels orientation, though; sometimes the pretzel is painted on a bakery sign belly-up, sometimes, belly-down, and there are even those compromise signs where it's been placed belly-sideways. This is yet another as-yet-unresolved dispute regarding the pretzel.[9]

The one thing that is common to pretzels from different regions (apart from the shape) is that they are steeped in lye (4% solution of sodium hydroxide), rather than boiled in water, prior to being baked. This is what gives them their smooth, but cracked, shiny copper-brown crust. According to the aforementioned legend, we owe lye pretzels to the Württemberger baker's cat, which accidentally dropped the unbaked pretzels into a vat of lye. As there was no time left to make new ones, the panicked baker just retrieved the pretzels from the lye and popped them into the oven, thus inventing the recipe that is still used today. Bavarians, though, have a different opinion on the lye pretzel's provenance: yes, they were invented by accident, only it wasn't in 15th-century Württemberg, but in 19th-century Munich.

| In the 19th century, a baker by the name of Anton Nepomuk Pfannenbrenner was working in Munich at the Royal Coffeehouse of Johan Eilles, purveyor to the Court. One day in 1839 whilst in the bakehouse he made a mistake which would have tremendous consequences. Although he would normally glaze the pretzels in sugar-water, on this particular day he accidentally used lye solution which was actually meant for cleaning the baking sheets. The result proved so impressive that on the very same morning, the lye pretzel was tasted by Wilhelm Eugen von Ursingen, an envoy of the King of Württemberg. The date of 11 February 1839 has since been considered the very first day a lye pretzel was sold. |

| — Publication of an application pursuant to Article 50(2)(a) of Regulation (EU) No 1151/2012 of the European Parliament and of the Council on quality schemes for agricultural products and foodstuffs (2013/C 262/06), EC No: DE-PGI-0005-0971, Official Journal of the European Union |

Obwarzanki

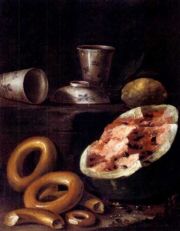

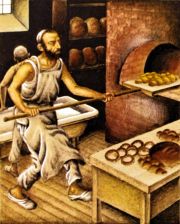

Notice the cauldron with boiling water, which may have been used to parboil the obwarzanki. Modern Polish cuisine is often described as combining two historical strains: on the one hand, the peasant cuisine, the poor, simple fare based on local and readily available ingredients; and on the other, the lordly cuisine of the nobility, sumptuous, abundant, exotic and following the rule, "pawn yourself, but show yourself". This view is somewhat oversimplified, though. Firstly, what people ate and drank had more to do with their actual income than the estate they were born into (for example, a relatively well-to-do peasant could eat just as well as a medium-income nobleman). And secondly, believe it or not, there were other social groups in Poland than just the peasantry and the nobility. Polish townsfolk, for instance, used to eat too, but they tend to be forgotten when historical Polish cuisine is being discussed. One reason for this may be that Polish towns were mostly populated by ethnic Germans and Jews, so their culinary heritage hasn't been included in the canon of ethnic Polish cuisine, which is mostly rural as a result. But there are at least two domains in which the culinary legacy of Polish towns has survived; these are beer brewing and bread baking. Sure, breweries and bakeries existed in the countryside as well, but it was the urban ones that were famous throughout the nation. The importance of urban bakers is still reflected today in the popularity of Poznań crescent rolls, Toruń gingerbread and yes, Cracovian obwarzanki. The oldest known mention of the Cracovian obwarzanek comes from the 14th century. A royal court accounting book from the times of Queen Hedwig and King Vladislav has the following expenditure recorded under the date 2 March 1394: "pro circulis obarzankij, for the Queen – 1 grosch." The Latin word, "circulis", shows that the breads in question were already round at the time. And the Polish word ("obwarzanki" in modern spelling), shows that they were parboiled (obwarzane) before baking. Just like pretzels, they were lean and luxurious goods at the same time,[10] which made them the perfect choice for the royal table during Shrovetide, which happened to include the 2 March that year. The Shrovetide was a pre-Lenten period of optional fasting. According to the accounting record from that particular day, Queen Hedwig, who would be later declared Saint Hedwig, ate 1 grosch worth of obwarzanki and three grosches worth of salted herrings; but the visiting Duchess of Masovia, who wasn't that keen of fasting, was served chicken instead.[11] Produkcja towarów luksusowych zawsze była lukratywnym biznesem, więc nic dziwnego, że cech piekarzy starał się zmonopolizować sprzedaż obwarzanków na terenie Krakowa. Udało się to w 1496 r, kiedy król Jan Olbracht wydał przywilej zezwalający na wypiek pszennego pieczywa – w tym obwarzanków – tylko piekarzom cechowym. Co więcej, obwarzanki można było wypiekać wyłącznie w Wielkim Poście. Przepis ten złagodzono nieco w 1720 r. (wypiek przez cały rok, ale tylko w dni postne), a ostatecznie zniesiono dopiero w połowie XIX w. Oczywiście nie wszyscy piekarze stosowali się do tych ograniczeń. Do połowy 1561 r. na północnych przedmieściach Krakowa (w rejonie dzisiejszego pl. Biskupiego i Pędzichowa) działały zakłady piekarzy niezrzeszonych w cechu, zwanych partaczami. Stosunki między piekarzami cechowymi a partaczami były mniej więcej takie jak między taksówkarzami a kierowcami Ubera, a ich kulminacją było spalenie piekarni partackich w Pędzichowie.[12] Z XVI w. pochodzi najstarsza znana wzmianka o tureckich chlebkach zwanych simitler, do złudzenia przypominających krakowskie obwarzanki. Jedne i drugie robi się z dwóch wałeczków drożdżowego ciasta splecionych w wieniec, ozdabia posypką, piecze, a na koniec sprzedaje ze specjalnych wózków. Różnica jest taka, że simitler nie obwarza się w wodzie z odrobiną miodu, tylko moczy w wodzie z melasą, sezamowa posypka jest znacznie obfitsza w wersji tureckiej, no i kolor wózków jest różny (w Krakowie – niebieskie, w Stambule – czerwone). Tylko że jeszcze na początku XX w. turecki simit miał kształt cienkiego pierścienia, a nie grubego wieńca, który to kształt krakowskie obwarzanki miały już najpóźniej w latach 20. tegoż stulecia. Trudno stwierdzić z całą pewnością, kto od kogo odgapił, ale lokalny patriotyzm każe mi przyjąć, że oryginalny kształt pochodzi jednak spod Wawelu. Tym bardziej że obwarzanki o takim właśnie kształcie nie są chyba znane nigdzie indziej w Polsce. Poza Krakowem, polskie obwarzanki to znacznie mniejsze i niezaplatane wypieki o gładkiej skórce. Słynne były na przykład obwarzanki smorgońskie, sprzedawane na jarmarkach kaziukowych w Wilnie. Zapewne taki właśnie kresowy obwarzanek miał na myśli Józef Piłsudski, gdy porównał doń Polskę, w której – jego zdaniem – najlepsze było właśnie to, co kresowe.

| Poland is like an obwarzanek; it's best around the edges. | ||||

— Józef Piłsudski, cyt. w: Ksawery Pruszyński: W Belwederze, in: Czas, 279, Kraków: 3 grudnia 1931, p. 3, own translation

Original text:

|

As promised, we divide equally: | ||||

— Władimir Władimirowicz Majakowski: [http://az.lib.ru/m/majakowskij_w_w/text_0190.shtml Misterija-buff [Мистерия-буфф, 1918, own translation

Original text:

|

Bajgle

| Paris has its baguettes and Dublin its soda bread. San Francisco trades heavily in sourdough, while New Orleans greets each morning with beignets. It wouldn't be Philadelphia without soft pretzels and it couldn't be Bonn without pumpernickel. But no city, perhaps in the history of the world, is so closely identified with a breadstuff as New York is with the bagel. |

| — Ed Levine: Was Life Better When Bagels Were Smaller?, in: The New York Times, 31 grudnia 2003 |

W jaki sposób krakowski wynalazek stał się nowojorską specjalnością? Bo że bajgiel wynaleziono w Krakowie, raczej nie ma wątpliwości. Najstarsza znana wzmianka o bajglach pochodzi z przepisów antyzbytkowych wydanych w 1610 r. przez krakowską (czy, właściwie, kazimierską) gminę żydowską. Ustawy antyzbytkowe miały zapewnić, by członkowie gminy nie wydawali zbyt dużo (stąd nazwa) na dobra luksusowe, co mogłoby niepotrzebnie prowokować ich chrześcijańskich sąsiadów. Co prawda, są rozbieżności w sprawie interpretacji przepisu dotyczącego bajgli; jedni uważają, że przepis ten zezwalał na kupowanie bajgli tylko tym Żydówkom, które właśnie urodziły dziecko (jako posiłek regeneracyjny?), a inni, że takie smakołyki jak bajgle wolno było spożywać podczas uroczystości z okazji obrzezania nowo narodzonego chłopca.[13] W każdym razie bajgiel, podobnie jak obwarzanek, był luksusem.

Z legendą, o tym jak bajgiel wynaleziono ku czci zwycięstwa króla Jana III pod Wiedniem, już się rozprawiliśmy przy innej okazji. Przypomnę więc tylko, że Sobieski rzeczywiście zasłużył się w pamięci żydowskich piekarzy z Krakowa w ten sposób, że jako pierwszy król od końca XV w. odmówił potwierdzenia przywileju, który dawał cechowi piekarzy krakowskich monopol na produkcję pieczywa z mąki pszennej.[14] A to znaczy, że Żydzi mogli wreszcie legalnie wypiekać bajgle i sprzedawać je na terenie miasta. Czym właściwie różniły się bajgle od obwarzanków? Wydaje się, że wtedy jeszcze niczym, poza tym że jedna nazwa pochodziła z języka polskiego, a druga – z jidysz. Dopiero później z jednego produktu wyewoluowały dwa różne wypieki – chrześcijański obwarzanek i starozakonny bajgiel. Pierwszy pozostał stosunkowo cienki, ale za to spleciony z dwóch wałków ciasta, drugi natomiast z czasem przeobraził się w pulchną bułkę z dziurką, którą można rozkroić na pół i zrobić z niej kanapkę. Pierwszego nie robi się do dziś nigdzie poza Krakowem (i dwoma sąsiednimi powiatami), za to drugi trafił wszędzie tam, dokąd dotarli krakowscy Żydzi.

W Cesarstwie Rosyjskim na przykład, bajgle stały się żydowskim odpowiednikiem bublików. Najlepiej widać to w refrenie żydowskiej wersji rosyjskiej piosenki, która pojawiła się w Odessie w czasach Nowej Polityki Gospodarczej (NEP, 1921–28), kiedy po raz pierwszy od wybuchu Wielkiej Rewolucji Październikowej można było legalnie sprzedawać prywatnie pieczone bułki z dziurką.

Come, buy my bublichki, | ||||

— Own translation into English from an anonymous Yiddish rendering of the original Russian song Bublichki by Yakov Yadov (ca. 1920)

Original text:

|

Zarówno przepis na bajgle, jak i piosenkę o nich, Żydzi wywieźli w końcu do Ameryki, a konkretnie – do ich największego skupiska, czyli Lower East Side (Dolnej Wschodniej Strony Manhattanu). Tym razem to kilka żydowskich rodzin zmonopolizowało wyrób bajgli, tworząc swój własny cech... Przepraszam, związek zawodowy. Związek, o nazwie Local 338, zrzeszał około trzystu piekarzy. Wszyscy byli mężczyznami wyznania mojżeszowego, porozumiewali się w języku jidysz, a członkostwo w związku przechodziło przeważnie z ojca na syna. Władze związku pilnowały, by przestrzegano dawnych receptur i by wszystkie bajgle, jak dawniej w Polsce, wyrabiano ręcznie.

Wśród konsumentów, jeszcze w połowie XX w., również byli wyłącznie Żydzi, dla których bajgiel – przekrojony na pół, posmarowany śmietankowym serkiem i złożony w kanapkę z marynowanym łososiem zwanym lox – był podstawą niedzielnego śniadania. Postęp techniczny w latach '60. zapoczątkował rewolucję w bajglowym biznesie. Bracia Lenderowie, których ojciec wypiekał bajgle jeszcze w Lublinie, najpierw odkryli, iż konsumenci nie zauważają różnicy między świeżymi a odmrożonymi bajglami, po czym nawiązali współpracę z Danielem Thompsonem, Kanadyjczykiem który wynalazł maszynę do wyrobu bajgli. Piekarze nie musieli już pracować po nocach, żeby zdążyć przed szczytem popytu w niedzielny poranek, a produkowane maszynowo mrożone bajgle zaczęły się pojawiać w supermarketach – również w okolicach niezamieszkanych przez Żydów. W ciągu dekady wojna Localu 338 z maszynami ostatecznie skończyła się tak jak walka cechu piekarzy krakowskich z partaczami. Dziś i cech piekarzy, i Local 338 należą do przeszłości, tak samo jak wyobrażenie o bajglu jako lokalnym, etnicznym i ręcznie robionym wypieku.

W 1993 r. statystyczny Amerykanin zjadał już po dwa bajgle miesięcznie. Co więcej, były to już bajgle mocno zamerykanizowane. W Ameryce duże jest piękne, więc bajgle, które w czasach Localu 338 ważyły ok. 70 g, teraz ważą po 200 g.[15] Wybór posypek wzrósł proporcjonalnie do wielkości bajgla; można je teraz kupić m.in. z makiem, kminkiem, sezamem, solą, czosnkiem, cebulą, borówkami, rodzynkami, czekoladą, cynamonem, no i oczywiście – ze wszystkim naraz (tzw. everything bagel).[16]

I tak nowojorskie bajgle i krakowskie obwarzanki, choć wywodzą się od tego samego wypieku z dawnej stolicy królów polskich, to ostatecznie podążyły różnymi liniami ewolucyjnymi. Aż wreszcie w 2001 r. historia potoczyła się obwarzankiem i bajgle wróciły do Krakowa, kiedy to Amerykanin Nava DeKime założył na Kazimierzu kawiarnię Bagelmama – pierwszy w lokal w Krakowie, gdzie można kupić bajgle zamiast obwarzanków.

Podsumujmy

Bawarski precel ma kształt węzła o trzech otworach, a przed wypieczeniem jest moczony w ługu. Obwarzanek krakowski ma formę wieńca splecionego z dwóch wałków ciasta, a przed pieczeniem obwarza się go w wodzie z odrobiną miodu. Amerykańskiego bajgla też się obwarza, ale ma kształt pulchnej bułki z dziurką w środku na tyle małą, że można z niego robić kanapki.

Uf! Nareszcie mamy prosty schemat, jak odróżnić te trzy wypieki od siebie. A teraz możemy go wyrzucić do kosza. Na Mazurach odwiedziłem właśnie stragan z nanizanymi na sznurki obwarzankami i preclami, które kształtem w żaden sposób nie różniły się od siebie. Okazało się, że tutaj precle od obwarzanków różni to, iż do ciasta na te pierwsze zamiast drożdży dodano jajek oraz że upieczono je bez uprzedniej kąpieli.

A jak to wygląda w innych regionach Polski? Dajcie znać w komentarzach. Tymczasem zaś porzućmy skazane na porażkę próby sklasyfikowania dziurawych bułek i weźmy się do jedzenia.

Przepis

Choć Amerykanie jadają bajgle na najprzeróżniejsze sposoby, to klasycznym zestawem pozostaje triada bajgiel–serek–lox, stanowiąca podstawę dawnych niedzielnych śniadań nowojorskich Żydów od co najmniej czwartej dekady XX w. Kiedy w 1984 r. firma Kraft Foods, do której należała marka serków Philadelphia, kupiła fabryki bajgli braci Lenderów, zorganizowano nawet wielki marketingowy ślub, gdzie panną młodą była wanna wypełniona serkiem, a panem młodym – ponaddwumetrowy bajgiel. Dwa lata później w jednej tylko fabryce Kraft Foods produkował już milion dziurawych bułek dziennie.[17]

Razem z Magdą, współautorką bloga Łowcy Smaków, postanowiliśmy zrobić sobie taki właśnie zestaw od podstaw. Magda upiekła bajgle, ja zająłem się dodatkami.

Ciasto moja przyjaciółka zrobiła z mąki pszennej (450 g), wody (250 g) i drożdży (1 paczka). Po wyrobieniu wstawiła do lodówki na noc. Następnego ranka uformowała z ciasta bajgle, dała ciastu urosnąć jeszcze godzinkę pod szmatką, po czym ugotowała je w wodzie z miodem i solą. Potem zostało już tylko posypanie bajgli sezamem i wstawienie ich do rozgrzanego do 200 °C pieca na jakieś 20 minut.

Jeśli chodzi o żydowski lox, to wprawdzie dzisiaj zastępuje się go często wędzonym łososiem, ale oryginalnie przypominał bardziej skandynawski gravlax, czyli łososia marynowanego w soli i zakopywanego w ziemi. Ja zrobiłem tak: grubą sól zmiksowałem pół na pół z cukrem, wraz z pęczkiem koperku oraz kilkoma ziarnami pieprzu i szyszkojagodami jałowca. Tą mieszaniną obłożyłem z obu stron płat surowego łososia i wszystko razem – nie, nie zakopałem, tylko owinąłem folią i wstawiłem na dwa dni do lodówki. Po tym czasie, zamarynowanego już łososia rozpakowałem, delikatnie oczyściłem z soli i cukru, i pokroiłem na cienkie plastry.

Z serkiem poszedłem trochę na łatwiznę, to znaczy zamiast ściąć mleko sokiem cytrynowym i w ten sposób zrobić serek, to po prostu zmiksowałem twaróg ze śmietaną i sokiem cytrynowym do smaku. Dla urozmaicenia zrobiłem też serki w innych wariantach smakowych: chrzanowym i jajeczno-szczypiorkowym.

I tyle. Na samo śniadanie trzeba było tylko poprzekrawać ciepłe jeszcze bajgle na pół, posmarować serkiem, przykryć plastrami łososia, przyozdobić cebulą i kaparami, i złożyć w kanapki. Było pysznie!

Bibliografia

- Maria Balinska: The Bagel: The Surprising History of a Modest Bread, New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2008 [1]

- Izabela Czaja, Marcin Gadocha: Obwarzanek krakowski: historia, tradycja, symbolika, Kraków: Bartosz Głowacki, 2008

- Andrew F. Smith: Savoring Gotham: A Food Lover’s Companion to New York City, Oxford University Press, 2016

References

- ↑ Description of the product according to: Publication of an application pursuant to Article 6(2) of Council Regulation (EC) No 510/2006 on the protection of geographical indications and designations of origin for agricultural products and foodstuffs (2010/C 38/08), EC No: PL-PGI-005-0674, Official Journal of the European Union

- ↑ Maria Balinska: The Bagel: The Surprising History of a Modest Bread, Yale University Press, 2008, p. 7

- ↑ Balinska, op. cit., p. 7

- ↑ Food Composition Tables for the Near East, Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 1982, p. 229

- ↑ Balinska, op. cit., s. 2–6

- ↑ Gillian Riley: Bread, ring-shaped, in: The Oxford Companion to Italian Food, Oxford University Press, 2007, p. 70–73

- ↑ Bre(t)z-, in: Atlas zur deutschen Alltagssprache, Universität Augsburg, Philologisch-Historischen Fakultät, 2016

- ↑ Krakelingen and Tonnekensbrand, end-of-winter bread and fire feast at Geraardsbergen, in: Intangible Cultural Heritage, UNESCO, 2010

- ↑ Fragen: Wer hat die Brezel erfunden? Und wo ist bei der Brezel eigentlich oben und wo unten?, Ulm: Museum Brot und Kunst – Forum Welternährung

- ↑ Balinska, op. cit., s. 14

- ↑ Alexander Przezdziecki: Życie domowe Jadwigi i Jagiełły: z regestrów skarbowych z lat 1388–1417, Warszawa: Skład główny w Księgarni Kommissowej Z. Steblera, 1854, p. 69–70

- ↑ Izabela Czaja, Marcin Gadocha: Obwarzanek krakowski: historia, tradycja, symbolika, Kraków: Bartosz Głowacki, 2008, p. 14–15

- ↑ Balinska, op. cit., s. 44–46

- ↑ Balinska, op. cit., s. 35

- ↑ Andrew F. Smith: Bagels, in: Savoring Gotham: A Food Lover’s Companion to New York City, Oxford University Press, 2016

- ↑ Jeremy Schneider: All 23 bagel flavors that matter, ranked worst to best, in: NJ.com

- ↑ Balinska, op. cit., s. 174–176

| ◀️ Previous | 📜 List of posts | Next ▶️ |

| ⏮️ First | 🎲 Random post | Latest ⏭️ |

[[Category: 19th century]