A Royal Banquet in Cracow

Among many tourist attractions in my beautiful hometown of Cracow (or Kraków, if you will), the former seat of the kings of Poland, there are two venerable establishments which pride themselves on dating back to the reign of King Casimir the Great -- specifically, to the year 1364. One of them is Poland's oldest institution of higher learning, the one where Copernicus went to college. King Casimir obtained papal consent to open a university in Cracow in 1364 indeed. But it took him three more years to actually open the Academy of Cracow, and three years after that King Casimir died and the Academy closed for business. It was only in 1400 that King Vladislav Jagailo and Queen Hewdig founded a new university in Cracow, which is known to this day as Jagiellonian University (and not Casimirian University). "Founded in 1364" turns out to be somewhat of a stretch.

Okay, but what does it have to do with culinary history? Nothing. That's why we're now going to focus on the other establishment, one which even has the year 1364 written into its logo. Here's what we can read about it in 1,000 Places to See Before You Die, a snobbish guidebook to the world's most overpriced hotels, restaurants and other tourist traps:

| Also on the square is the historic restaurant Wierzynek, the best place to enjoy courtly European service and traditional Polish specialties. Said to be one of the oldest operating restaurants in Europe, its history goes back to 1364, when inkeeper Mikolaj Wierzynek created a banquet served on gold and silver plates for the guests of King Casimir the Great, including Holy Roman Emperor Charles IV. Wierzynek restaurant has hosted every visiting head of state ever since. Experience 500 years of history at the elegant café downstairs or the venerable upstairs salon, where seasonal game, mountains trout, and mushroom-sauced delights are served amid decorative reminders of the establishment's gloried past. |

| — Patricia Schultz: 1,000 Places to See Before You Die: A Traveler's Lifelist, New York: Workman Publishing, 2003, p. 300 |

As a child, I too was convinced that this restaurant -- back then passing for the best in town, if not in all Poland (largely due to the lack of competition) -- had been founded in 1364 by Mikołaj Wierzynek (pronounced mee-KAW-wye vyeh-ZHIH-neck), who must have been, therefore, Poland's first restaurateur. My first doubts appeared when I read that restaurants in general are a 19th-century invention and that medieval monarchs avoided dining in taverns or inns, unless they had absolutely no choice. And together with doubts came questions: What was this banquet in Cracow about? Who took part in it and why? What kind of food was served? Who was this Wierzynek and what role did he serve in the banquet? And when was the restaurant bearing his name and located at Europe's largest city square really opened?

These are the questions I'm going to try and answer today.

A Diplomatic Summit or a Family Reunion?

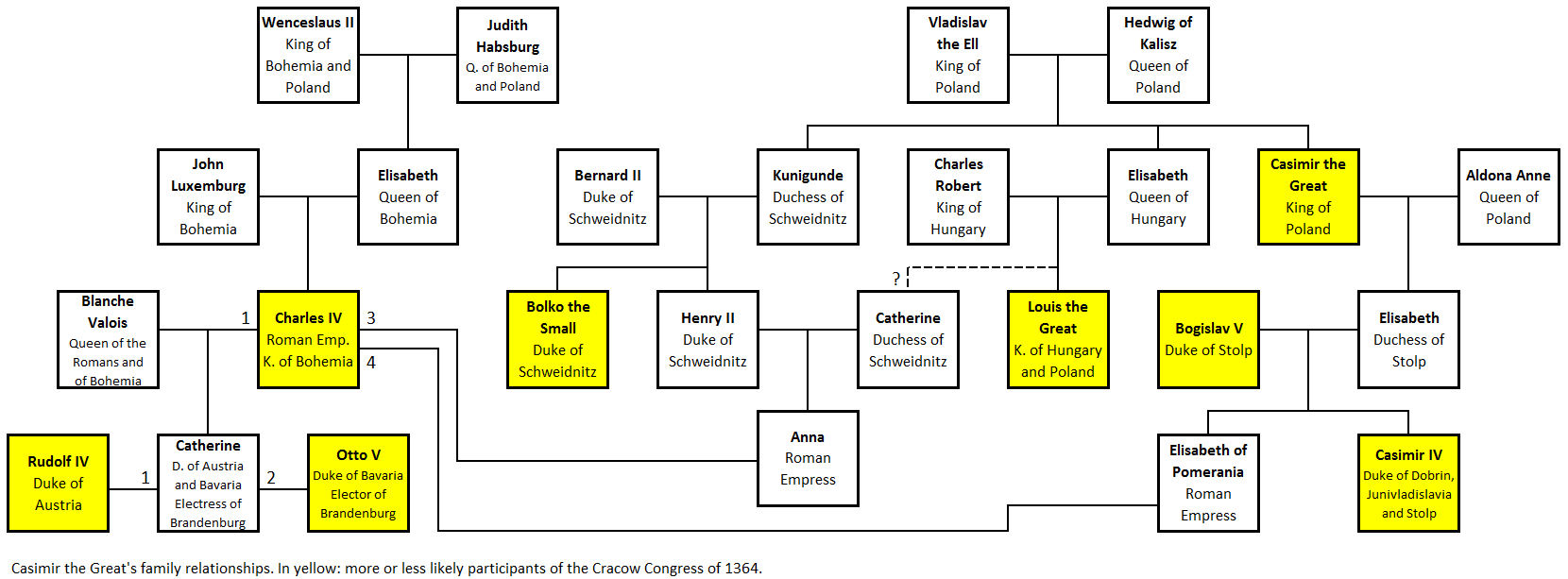

The only historical source that mentions the banquet at Wierzynek's are the Annals of the Glorious Kingdom of Poland by Jan Długosz, also known by his Latinized name, Joannes Longinus. According to his account, it all began when Charles of Luxembourg, emperor of the Holy Roman Empire and king of Bohemia (a kingdom roughly corresponding to the modern-day Czech Republic) was receiving envoys from Hungary and said something very offensive about King Louis of Hungary's mom. It led, obviously, to a major diplomatic crisis. Louis, together with Duke Rudolph Habsburg of Austria (who also had his differences with the emperor and, incidentally, his father-in-law), was getting ready for war. This is when Pope Urban V decided it was enough that Western Europe, recently ravaged by a pandemic of bubonic plague, was already being plunged into a bloody conflict (which would later come to be known as the Hundred Years' War). Having rulers of the relatively stable and quickly developing Central Europe at each other's throats would be too much. Which is why he dispatched his nuncio, Peter of Volterra, to try and calm them down. The nuncio did a great job -- he managed to prevent hostilities and to convince the wrangling monarchs to settle their argument through arbitration. It was agreed there would be two adjudicators: one was Duke Bolko the Small of Schweidnitz, the last sovereign ruler in Silesia and uncle of the emperor's recently deceased third wife. The other was King Casimir of Poland, brother of the Hungarian queen mother whose honour had been besmirched.

The nuncio also engaged in matchmaking and arranged the marriage of the freshly widowed emperor with Casimir's granddaughter, Duchess Elizabeth of Stolp, Pomerania. The wedding was held in Cracow. According to Longinus, people invited by King Casimir included -- apart from the young bride (and her family) and the not-so-young groom (and his family) -- King Louis of Hungary, King Sigismund of Denmark, King Peter of Cyprus, Duke Bolko the Small of Schweidnitz, Duke Otto V of Bavaria, Duke Semovit of Masovia, Duke Vladislav II of Opole etc. The wedding reception lasted twenty days, during which barrels of wine were put out in the streets for the common folk, while the royals and lords enjoyed tournaments, dances and banquets. The festivites were overseen -- again, according to Longinus -- by a certain Wierzynek, "a councillor of Cracow, native of the Rhineland" and "manager of the royal treasury". He held one of the banquets in his own home, where -- in gratitude for "unspeakable benevolence" -- he seated King Casimir (and not the emperor!) in the place of honour and showered him with presents that were worth more than the new empress's dowry.[1]

So much for Longinus. Unfortunately, historians realized long ago that much of this story is at odds with what you can read in other historical documents, especially in the Cracow cathedral chronicle, the Annals of the Holy Cross (although these contain errors too, which Longinus merely repeated) and The Capture of Alexandria, an epic poem by Guillaume de Machaut (more about which later). Neither the date, nor the purpose, nor the guestlist of the event turned out to be exactly as the chronicler claimed they were. This is how these discrepancies were summed up at the end of the 19th century by prof. Stanisław Kutrzeba:

| Clear-headed historical criticism does not fully trust Longinus, who tends to combine distinct facts, seek relationships among them where there aren't any and embellish his account with more than just stylistic additions. No more did the beautiful story of a king's fight for his sister's honour and of his granddaughter's wedding survive the scalpel of critique. Doubts, minor at first, eventually dismantled almost entirely the structure which Longinus had skillfully pieced together. | ||||

— S. Kutrzeba, Krakowski zjazd monarchów, czyli uczta u Wierzynka,, p. 53, own translation

Original text:

|

As it happens, the great Cracovian chronicler, writing a century after the actual events, combined at least three separate mettings of Central European monarchs which took place in Cracow in the years 1363–1364 into one big congress. First there was the imperial wedding in May 1363. Louis wasn't there as he hadn't yet reconciled with the emperor, nor had the kings of Denmark and Cyprus any reason to attend. The bride and groom's families were certainly there, so we can presume the presence of some people not mentioned in the sources, such as the emperor's brother John Henry, Margrave of Moravia, or Casimir of Stolp, the bride's brother and King Casimir's favourite grandson.

In December of the same year Bolko the Small arrived in Cracow, so that he and King Casimir could finally adjudicate on the dispute between Charles and Louis. It's possible that King Valdemar IV of Denmark (not Sigismund, as Longinus writes) was in town at the same time on unrelated business.

Finally, in September 1364, Emperor Charles and King Louis convened in Cracow to reconcile and swear friendship to each other, as mandated by Casimir and Bolko's arbitration. This was a purely political gathering, not a family event, so most likely without women. Other participants may have included dukes of Austria, as parties to the dispute, other aforementioned dukes and -- quite coincidentally -- King Peter of Cyprus.

Let's take a closer look at this somewhat exotic ruler. The Kingdom of Cyprus was established after crusaders led by King Richard the Lionheart had conquered the Christian, but strategically located, island. From then on, it was ruled by Catholic kings of the French house of Lusignan. Most of the time they were warring against the equally Catholic city of Genoa, but for PR reasons they promoted the need to fight the Arabs and the Turks. And so, in 1362, King Peter set out on a tour of Europe to gather volunteers and money for a new crusade against the infidels. He travelled through Italy, France, what is now Belgium, England and Germany. He collected quite a sum of money, but the he was robbed and had to start again from scratch. Eventually he got to Prague, where the emperor proposed to take him to a big get-together of monarchs in Cracow, where he was just getting ready to go and where Peter could propagandize his idea for a crusade.

Years later Guillaume de Machaut would sing of King Peter's peregrination, as well as the actual crusade against Egypt, in The Capture of Alexandria. According to de Machaut's account, Charles and Peter leaved Prague on horseback, entering Silesia (a region between Bohemia and Poland) after three days, then passed a number of Silesian and Polish towns (some of which couldn't possibly be on their itinerary, so it looks like the poet just listed the place names he happened to know) and finally reaching Cracow, where they were greeted by other monarchs with much rejoicing. During the congress, the monarchs politely lent their ears to Peter's pleas and then supported his crusading efforts by letting him win the main prize in a tournament.

The Bourgeois Nobleman

As for Wierzynek, Longinus gives us only his surname. A merchant family of this name, one of Cracow's most affluent and influential, used to live in the city for centuries. Its progenitor, Mikołaj Wierzynek, arrived in Cracow from the Rhineland, or what is now western Germany, at the beginning of the 14th century. And of course his name wasn't really Mikołaj Wierzynek, but Nikolaus Wirsing; it was only years later that his descendants Polonized the German surname to "Wierzynek". He served as a member of the city council of Cracow and later as a mayor of the nearby salt-mining town of Wieliczka. He was even named Pantler of Sandomierz, but it doesn't mean he was actually responsible for the royal pantry whenever the king was in that city; it had already become a purely titular office, but it carried great prestige and was reserved for the nobility. So how did a Rhenish merchant become a Polish nobleman? We don't know for sure, but there were basically three options to achieve this status: ennoblement, naturalization and imposture. Whichever it was, Wirsing was certainly a man of means who enjoyed a high level of the king's trust -- in other words, an ideal candidate for organizing a great banquet designed to wow the emperor and other monarchs, and to glorify Casimir the Great's kingdom, which was just making its debut as a serious player on the international stage.

There's only one but: Pantler Nikolaus Wirsing died in 1360, that is, 3--4 years before the banquet. So if it wasn't him who threw the most famous party of medieval Poland, then it must have been one of his family members. His family grew quickly after he had settled in Cracow, but historians have been able to identify one particular Wirsing who could have been responsible for the banquet; it was the pantler's son, Nikolaus Wirsing Junior, who, like his father, served as a Cracow councillor and, unlike his father, isn't known to have accomplished much else. Hence the conclusion that Junior held the banquet, perhaps in his own house, but he did it in the name of the city, spending money from the city's budget.[2]

- ↑ Jan Długosz: Roczniki czyli kroniki sławnego Królestwa Polskiego: księgi IX–XII (wybór), translated into Polish by Karol Mecherzyński, Zrodla.Historyczne.prv.pl, 2003, p. 14

- ↑ S. Kutrzeba, op. cit.