Holey Breads

Okay, so this post isn’t about holy breads – as in the Eucharist. It’s about breads with holes. And I don’t mean little pockets of air as in sourdough bread. I mean breads that are shaped like rings, wreaths or knots, with the dough surrounding one or more holes. You know, bagels, pretzels and the like.

In a few shopping malls and other places in Warsaw you can find stands like the one pictured here, selling what the sign claims to be krakowskie precle, or “Cracow pretzels”. Intriguingly, the company that distributes them in Warsaw proudly boats that these “pretzels” are shipped each morning straight from Mr. Czaja’s bakery in Cracow. But if we take a look at Mr. Grzegorz Czaja’s bakery website, we’ll see that what he bakes there is not pretzels, but something called obwarzanki🔊. It seems as though the obwarzanki magically turned into pretzels the moment they arrive in Warsaw! Can we chalk it up to merely yet another linguistic difference between Cracovian and Warsovian Polish? Or is there a more profound distinction between pretzels and obwarzanki?

“Pretzels, “bagels” and “obwarzanki” are all used by tourists and native Cracovians alike to refer to the specifically Cracovian bread which “takes the form of an oval with a hole in the middle” and whose “surface is formed by strands of dough twisted into a spiral”.[1] Although unique to Cracow, it nonetheless belongs to the great diverse family of holey breads. So let’s take a look at the bigger picture now.

Common Ancestors

Bagels, pretzels and obwarzanki are similar enough to each other to suggest a common origin. According to Ms. Maria Balinska, who wrote a book on the history of bagels, holey breads date back all the way to ancient Rome. She believes that all such bread products descend from the buccellata,[2] or small, round, jaw-breaking double-baked biscuits used as army hardtack by Roman legionaries at least as early as the 4th century CE. Whether they were actually ring or rather disc-shaped is uncertain. The author of Pass the Garum, a blog about ancient Roman foodways, reconstructed them as the latter, with only little holes punched with a needle to let air and steam escape during baking. Another hypothesis, also mentioned by Ms. Balinska, says that the buccellatum was the ancestor of the round communion wafer used by Christians in the sacrament of the Eucharist.

Another bread with a long history, which, this time for sure, is made in the shape of elongated rings, is the Middle Eastern ka’ak. These breads get a mention in the Talmud,[3] so they must have been known at least as early as the 6th century CE. Unlike the overly simple buccellata, made only of flour, salt and butter, ka’ak are made from leavened dough. What’s interesting is that the leavening agent used here is not yeast, but fermented chickpea.[4] Generously sprinkled with sesame seeds before baking, ka’ak may be still purchased in the streets of Arab and Israeli cities.

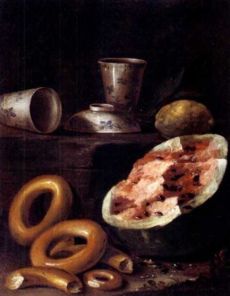

Let’s go back to the Apennine Peninsula. It was in the ports of Apulia, a region of southern Italy, that taralli were being boiled and baked as early as the 14th century. That’s right, it’s a kind of bread that is first boiled and only then baked. Why? Because when the starch on the surface of the dough comes into contact with boiling water, it gets gelatinized, giving the tarallo its shiny and crunchy crust. The stiffened crust also prevents the dough from rising further during baking, which helps keep the bread in shape. And this, in turn, means that you can make bigger ring-shaped breads than you could without boiling them first.[5] Clever, huh?

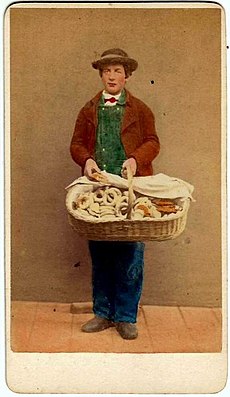

Great, but what’s the deal with the ring shape in the first place? Why not a ball or a disc, but a torus, which takes a lot more skill to form? Well, this shape has two advantages. First, a bread with a hole has only a slightly smaller volume with a much larger surface area than a whole bread of comparable size (the proof by calculating the surface areas and volumes of a torus and an ellipsoid is left as an exercise for the Reader). And a greater surface area allows the heat to spread more evenly inside the dough during the thermal treatment (boiling or baking). Secondly, a holey bread is easier to transport, especially for a street vendor who can just put his (somehow it’s usually been men) taralli on a string or a stick and peddle them in the street. And the customers could even wear their tarallo like a bracelet, if they didn’t eat it right away.

Dry taralli were used in a similar way as the ancient buccellata in that they could be stored for up to half a year and then eaten after being dunked in wine for softening. Were these toroidal taralli inspired by the Arab ka’ak, brought by Levantine sailors to Apulian ports? Quite possibly, but we don’t know that for sure. Whatever the case, soon after the taralli had appeared in southern Italy, similar breads were being made in the north. They bore a plethora of regional names, including “bricuocoli”, “ciaramilie”, “pane del marinaio”, “mescuotte”, “ciambelle”, “ciambelloni”, “braciatelle”, “brazzatelle” and “brasadèle”[6] (the latter three are reminiscent of “braccialetto”, the Italian word for “bracelet”; ultimately, both “braciatella” and “braccialetto” derive from Latin “bracchium”, meaning “arm”).

Pretzels

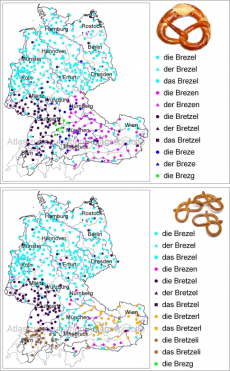

The Italian “la brazzatella“ sounds quite similar to the German “die Brezel”… Or is it “das Brezel”? Or “der Brezel”? German speakers can’t agree on the grammatical gender of their pretzels. The jury is also out on whether the first “e” in this word is long or short (as in “der/die/das Bretzel”). There are also those, mostly in Bavaria and Austria, who call it “die Brezen” (or “der Brezen”). Or even “die Brezg”, as they say along the Bavarian-Swabian border.[7] What they all do agree on is the pretzel’s shape. Not a ring, not a wreath, but a knot which looks like two sixes conjoined at their bellies, with not one, but three holes.

The pretzel’s grammatical gender is also an important issue in France, allowing Alsatians to tell an authentic Alsatian pretzel from a fake non-Alsatian one. Or so at least claims one Alsatian blogger:

| “Le bretzel” is this little unspeakable, incongruous and indigestible thing sold by packets in the supermarkets across the Vosges. “La bretzel” is a succulent Alsatian speciality. | ||||

— PiP, vélodidacte: L’histoire de la Bretzel selon l’Hortus Deliciarum, in: Autour du Mont-Sainte-Odile, Overblog, 2013, own translation

Original text:

|

The same blogger proves that pretzels have been known in Alsace since at least the 13th century, because you can find their images in Hortus Deliciarum (Garden of Delights), a kind of medieval illustrated encyclopedia. It was created by Herrad of Landsberg, an abbess of the convent on Mount Saint Odile in the eastern Vosges. You can see breads twisted into the unmistakable pretzel shape in three illuminations depicting Biblical figures seated at a table. What’s interesting is that in all three pictures the pretzels lie right next to fish.

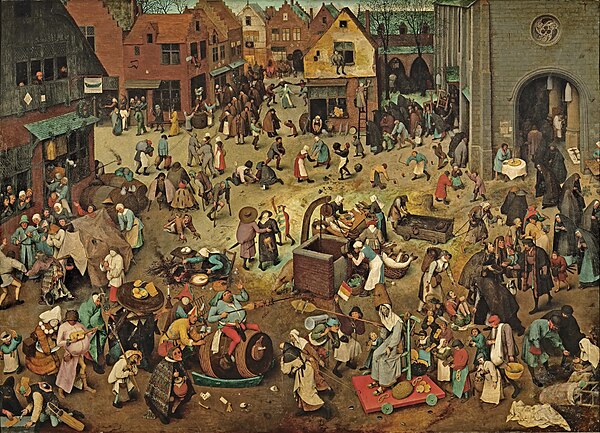

What might pretzels have to do with fish? Well, neither of them contains any ingredients of land-animal origin (pretzel dough contains no eggs or butter), which means they may be safely consumed during a period of Catholic fast. Along with fish, the pretzel used to be one of the chief symbols of Lent, which is best illustrated by Pieter Brueghel’s famous painting, The Fight Between Carnival and Lent.

And because pretzels were made from the relatively expensive wheat flour, they were not only a lean product, but also a luxury one. Some of those who could afford them couldn’t even wait until Lent and would start eating them already in the carnival. And so in some parts of Germany and the Low Countries has the pretzel become a traditional carnival treat. In many towns pretzels are given away during carnival parades. The Flemish town of Geraardsbergen is still known for its tradition of throwing little pretzel-shaped sugar-covered cookies called krakelingen into the crowd on the first Monday of March.[8]

But where does this shape come from anyway? Nobody seems to know for sure; even the legends don’t agree. One says that the shape of the pretzel is designed to resemble the arms of a monk folded in prayer. According to another one, it was invented by a baker from Württemberg who had been sentenced to death, but whom Count Eberhard von Urach promised to pardon on the condition that he bakes a bread through which the sun would shine three times. In any case, the pretzel shape is so distinctive that bakers’ guilds throughout central Europe would adopt it as their coats of arms. You can still find it on the shop sign of many a German bakery. There are differences in the pretzel’s orientation, though; sometimes the pretzel is painted on a bakery sign belly-up, sometimes, belly-down, and there are even those compromise signs where it’s been placed belly-sideways. This is yet another as-yet-unresolved dispute regarding the pretzel.[9]

The one thing that is common to pretzels from different regions (apart from the shape) is that they are steeped in lye (4% solution of sodium hydroxide), rather than boiled in water, prior to being baked. This is what gives them their smooth, but cracked, shiny copper-brown crust. According to the aforementioned legend, we owe lye pretzels to the Württemberger baker’s cat, which accidentally dropped the unbaked pretzels into a vat of lye. As there was no time left to make new ones, the panicked baker just retrieved the pretzels from the lye and popped them into the oven, thus inventing the recipë that is still used today. Bavarians, though, have a different opinion on the lye pretzel’s provenance: yes, they were invented by accident, only it wasn’t in 15th-century Württemberg, but in 19th-century Munich.

| In the 19th century, a baker by the name of Anton Nepomuk Pfannenbrenner was working in Munich at the Royal Coffeehouse of Johan Eilles, purveyor to the Court. One day in 1839 whilst in the bakehouse he made a mistake which would have tremendous consequences. Although he would normally glaze the pretzels in sugar-water, on this particular day he accidentally used lye solution which was actually meant for cleaning the baking sheets. The result proved so impressive that on the very same morning, the lye pretzel was tasted by Wilhelm Eugen von Ursingen, an envoy of the King of Württemberg. The date of 11 February 1839 has since been considered the very first day a lye pretzel was sold. |

| — Publication of an application pursuant to Article 50(2)(a) of Regulation (EU) No 1151/2012 of the European Parliament and of the Council on quality schemes for agricultural products and foodstuffs (2013/C 262/06), EC No: DE-PGI-0005-0971, Official Journal of the European Union |

Obwarzanki

Modern Polish cuisine is often described as combining two historical strains: on the one hand, the peasant cuisine, the poor, simple fare based on local and readily available ingredients; and on the other, the lordly cuisine of the nobility, sumptuous, abundant, exotic and following the rule, “pawn all, but give a ball”. This view is somewhat oversimplified, though. Firstly, what people ate and drank had more to do with their actual income than the estate they were born into (for example, a relatively well-to-do peasant could eat just as well as a medium-income nobleman). And secondly, believe it or not, there were other social groups in Poland than just the peasantry and the nobility. Polish townsfolk, for instance, used to eat too, but they tend to be forgotten when historical Polish cuisine is being discussed. One reason for this may be that Polish towns were mostly populated by ethnic Germans and Jews, so their culinary heritage hasn’t been included in the canon of ethnic Polish cuisine, which is mostly rural as a result. But there are at least two domains in which the culinary legacy of Polish towns has survived; these are beer brewing and bread baking. Sure, breweries and bakeries existed in the countryside as well, but it was the urban ones that were famous throughout the nation. The importance of urban bakers is still reflected today in the popularity of Poznań crescent rolls, Toruń gingerbread, Lublin onion pastries and yes, Cracovian obwarzanki.

The oldest known mention of the latter comes from the 14th century. A royal-court book of accounts from the times of Queen Hedwig and King Vladislaus Jagailo has the following expense recorded under the date 2 March 1394: “pro circulis obarzankij, for the Queen – one penny.” The Latin word “circulis” shows that the breads in question were already round at the time. And the Polish word (“obwarzanki” in modern spelling), shows that they were parboiled (obwarzane) before baking. Just like pretzels, these were lean and luxury goods at the same time,[10] which made them the perfect choice for the royal table during Shrovetide, which happened to include the 2 March that year. Shrovetide was a pre-Lenten period of optional fasting. According to the ledger record from that particular day, Queen Hedwig, who would be later declared Saint Hedwig, ate one penny worth of obwarzanki and three pence worth of salted herrings, while the visiting Duchess of Masovia, who wasn’t that keen of fasting, was served chicken instead.[11]

Production of luxury goods has always been a lucrative business, so it’s no wonder that the guild of bakers sought to monopolize the sale of obwarzanki within the city walls of Cracow. They achieved this goal in 1496, when King John Albert issued a decree restricting the production of white bread (including obwarzanki) to guild members. What’s more, obwarzanki could only be baked during Lent. This law was somewhat relaxed in 1720 (baking allowed on all lean days throughout the year, not just in Lent) and eventually abolished only in the mid-19th century. Naturally, not all bakers would follow these rules. Until 1561, there were bakeries in the northern suburbs of Cracow whose owners didn’t belong to the guild. The English language doesn’t really seem to have a word for this kind of outside-the-guild craftsman; he would have been called “partacz” in Polish and “Pfuscher” in German, both of which may be roughly translated as “botcher” or “bungler”. As you can imagine, relations between guild members and the “bunglers” were about as cordial as those between taxi and Uber drivers, and they got most heated when the guild bakers eventually burned the “bunglers’ ” bakeries down.[12]

From the 16th century comes the oldest known mention of the Turkish bread products called simit, which bear an uncanny resemblance to the Cracovian obwarzanki. Both kinds of bread are made of two strands of dough that are braided into a wreath, sprinkled with sesame seeds, baked and finally sold in the streets from special carts. There are some differences too: the simit aren’t parboiled, but just steeped in a mixture of water and molasses; the sesame seed sprinkle is much more generous in the Turkish version; and the carts are different colours (blue in Cracow, red in Istanbul). However, as recently as the early 20th century, the Turkish simit had the form of a thin single-strand ring; the obwarzanek in Cracow, on the other hand, was shaped into the wreath form no later than the 1920s. I can’t tell who copied from whom with absolute certainty, but my local patriotism requires me to assume that this distinctive shape was born at the foot of the Wawel Hill.

Especially that obwarzanki of this particular shape are practically unique to Cracow. Polish obwarzanki outside Cracow are much smaller, unbraided, single-strand rings with smooth crust. Among these, Smorgonian obwarzanki (from what is now Smarhon, Belarus) were particularly famous, as they were sold at the yearly Saint Casimir’s fair in Wilno (now Vilnius, Lithuania). It was probably this kind of obwarzanek from Poland’s borderlands that Marshal Józef Piłsudski had in mind when making a similë between the nation and the ring-shaped bread.

| Poland is like an obwarzanek; it’s best around the edges. | ||||

— Józef Piłsudski, cyt. w: Ksawery Pruszyński: W Belwederze, in: Czas, 279, Kraków: 3 December 1931, p. 3, own translation

Original text:

|

You can find similar breads even further east, where the word “obwarzanek” has evolved into “baranka”. Apart from baranki, the East Slavs (Russians, Belarusians and Ukrainians) also bake the slightly larger bubliki and the slightly smaller sushki. The bubliki have made a particularly interesting career not only in the culinary realm, but also in song and literature. Mostly as a symbol of poverty; bakers may have been relatively well off, but the peddlars who distributed the bubliki earned next to nothing. The only thing worth less than a bublik was the bublik hole.

As we’ve promised, we divide equally: | ||||

— Vladimir Vladimirovich Mayakovsky: Misteriya-buff [Мистерия-буфф], 1918, own translation

Original text:

|

Bagels

| Paris has its baguettes and Dublin its soda bread. San Francisco trades heavily in sourdough, while New Orleans greets each morning with beignets. It wouldn’t be Philadelphia without soft pretzels and it couldn’t be Bonn without pumpernickel. But no city, perhaps in the history of the world, is so closely identified with a breadstuff as New York is with the bagel. |

| — Ed Levine: Was Life Better When Bagels Were Smaller?, in: The New York Times, 31 December 2003 |

So how has a Cracovian invention got to be a New York speciality? Because there’s no doubt that Cracow is the bagel’s original hometown. The first known mention of bagels comes from sumptuary laws issued in 1610 by the Jewish community in what was then Poland’s capital. The purpose of sumptuary laws was to prevent members of the community from overspending on luxury goods lest they provoke their gentile neighbours with their ostentatious wealth. As for what the law was actually saying on the topic of bagels, there are conflicting interpretations. Some say that the regulation allowed only those Jewish women who had just given birth to buy bagels. Others argue that bagels were allowed only on special occasions such as the circumcision of a newborn boy.[13] Whatever the case, one thing is sure: the bagel, just like the obwarzanek, was a luxury.

With the legend about how the bagel was invented in honour of King John III Sobieski’s victory at Vienna, we’ve already dealt in one of the previous posts. Let’s just recall here that Jewish bakers were indeed indebted to King John, as he was the first Polish monarch since the end of the 15th century not to confirm the Cracovian guild of bakers’ monopoly on white bread.[14] What this meant for the Jews was that they could finally bake their own bagels and sell them within the walls of Cracow. So how exactly did the bagels differ from the obwarzanki? Well, it seems that at the time the only difference was that obwarzanki was a Polish word and beygl was Yiddish. It was only later that two different bread products would evolve from the same common ancestor: the gentile obwarzanek and the Jewish bagel. The former had remained relatively thin, but braided from two strands of dough; the latter has evolved into a roll with a little hole, plump enough to be cut in half and fashioned into a sandwich. The former isn’t made anywhere outside Cracow and the two adjacent counties, the latter has spread to all places reached by Cracovian Jews.

In the Russian Empire, for instance, bagels would become the Jewish equivalent of the bubliki. You can best see it in the chorus of the Yiddish version of a Russian song written in Odessa during the New Economic Policy (1921–28), when for the first time since the Great October Revolution one could legally sell privately baked rolls with holes.

Come, buy my bublitchki, | ||||

— Own translation into English from an anonymous Yiddish rendering of the original Russian song Bublichki by Yakov Yadov (ca. 1920)

Original text:

|

Jewish immigrants would eventually bring both the recipë for bagels and the song to America and, specifically, to the Lower East Side of Manhattan. It was here that a few families – Jewish this time around – would monopolize bagel production by setting up their own guild… I mean, trade union. The union, known as Local 338, counted about 300 bakers among its members. They were all Yiddish-speaking men of the Jewish persuasion, with membership typically passing from father to son. All union bakers made their bagels by hand, just like back in the old country.

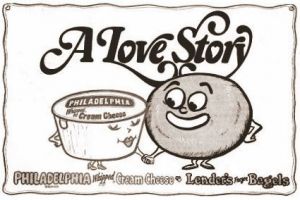

Up to the mid-20th century all of their customers were Jewish too. For New York Jews, a sandwich of bagel schmeared with cream cheese and garnished with lox was the foundation of a typical Sunday breakfast. But the 1960s eventually saw a revolution in the bagel business, brought about by technological progress. First, the Lender brothers, whose father had been a bagel baker back in Lublin, discovered that consumers couldn’t tell between a fresh bagel and a defrosted one. Then they leased a bagel-making machine invented by the Canadian Daniel Thompson. The bakers no longer had to work all night long to make enough bagels for the Sunday morning peak. Frozen machine-produced bagels started to show up in supermarkets – also in gentile neighbourhoods. Within a decade, Local 338’s war against machines ended with the same result the Cracovian guild of bakers’ fight against the “bunglers” eventually did. Today, both the guild and the trade union are gone, just like the idea of a bagel as a local, ethnic and hand-made bread product.

In 1993, a statistical American was already consuming two bagels per month. What’s more, by that time, the bagels had become thoroughly Americanized. In America, big is beautiful, so bagels, which weighed only 2–3 oz. (70 g) back in the times of Local 338, have been supersized to an average weight of 7 oz. (200 g).[15] The choice of sprinkles has grown proportionally to the size of the bagel itself; you can now have bagels sprinkled with poppy seeds, caraway, sesame seeds, garlic powder, onion flakes, blueberries, raisins, chocolate chips, cinnamon… and of course, everything at once.[16]

And so, divergent evolutionary paths have led to obwarzanki in Cracow and bagels in America. But in 2001, history came a full circle and the bagels finally returned to Cracow. This was when the American Nava DeKime came to Kazimierz, the former Jewish district of Cracow, and opened Bagelmama – the first café in Cracow where you can buy bagels instead of obwarzanki.

To Sum Up

A Bavarian pretzel is shaped like a knot with three holes and it’s steeped in lye prior to baking. A Cracovian obwarzanek has the form of a wreath braided from two strands of dough and it’s boiled in water with a little honey before baking. An American bagel is also parboiled, but it looks like a plump roll with a hole small enough to allow making bagels sandwiches.

There! We’ve finally got a simple guideline to tell these three bread products apart. And now… we may forget about it. I’ve just visited a stand in Masuria (former East Prussia) with strings of pretzels and obwarzanki, and you know what? They all had the exact same shape! It turns out that in Masuria, the difference between pretzels and obwarzanki is that the former have eggs added to the dough and they’re baked without bathing them in water first.

So, what’s the holey-bread-related terminology where you come from? Please let me know in the comments. But for now, let’s leave the doomed effort to classify holey breads aside and let’s make ourselves something to eat!

Recipë

Even though Americans have their bagels with all kinds of fixings nowadays, the bagel – cream cheese – lox triade remains the classic combination. It has been the feature of New York Jews’ Sunday breakfasts since at least the 1930s. When Kraft Foods, who already owned the Philadelphia cream-cheese brand, acquired the Lender brothers’ bagel business in 1984, they even organized a grand marketing wedding ceremony, where the bride was a cream-cheese-filled tub and the groom was an eight-foot (over 2 m) bagel. Two years later, just one of the factories Kraft Foods had bought from the Lenders churned out a million holey bread rolls per day.[17]

This classic set is what Magda, co-author of the blog Łowcy Smaków (Flavour Hunters), and I decided to make from scratch for breakfast (some advance preparation was needed). Magda baked the bagels and I made the rest.

My friend first made the dough from wheat flour (450 g), water (250 g) and instant yeast (1 packet), and after some kneading she left it the fridge for one night. Next morning, she formed the bagels, let the dough rise for an hour under a piece of cloth and then boiled them in water with some honey and salt. All that was left to do afterwards was to sprinkle the bagels with sesame seeds and pop them into an oven preheated to 200 °C for some 20 minutes.

As for the Jewish lox, it tends to be replaced with smoked salmon today, but the real deal is more like the Scandinavian gravlax, that is, salmon pickled in salt and buried in the ground to marinate. So this is what I did: I mixed equal amounts of coarse salt and sugar, as well as a bunch of dill and a few crushed peppercorns and juniper berries. I spread the mixture on both sides of a salmon fillet and then – no, I didn’t bury it; I just wrapped it in plastic foil and left in the fridge for two days. Then I unpacked it, gently brushed away the salt-and-sugar mixture, and cut the lox into paper-thin slices.

For the cream cheese, I decided to take a shortcut. Rather than curdling milk with lemon juice to make the cheese from scratch, I just blended some Polish twaróg, or farmer cheese, with cream and a little lemon juice for taste. For a change of pace, I also made cheese spreads with other flavours: eggs-and-chives and horseradish.

And that’s it. All we had to do for breakfast was to slice the freshly baked bagels in half, spread the schmear on them, cover with slices of the marinated salmon and garnish with onion rings and capers. It was delicious!

Bibliography

- Maria Balinska: The Bagel: The Surprising History of a Modest Bread, New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2008

- Izabela Czaja, Marcin Gadocha: Obwarzanek krakowski: historia, tradycja, symbolika, Kraków: Bartosz Głowacki, 2008

- Andrew F. Smith: Savoring Gotham: A Food Lover’s Companion to New York City, Oxford University Press, 2016

References

- ↑ Description of the product according to: Publication of an application pursuant to Article 6(2) of Council Regulation (EC) No 510/2006 on the protection of geographical indications and designations of origin for agricultural products and foodstuffs (2010/C 38/08), EC No: PL-PGI-005-0674, Official Journal of the European Union

- ↑ Maria Balinska: The Bagel: The Surprising History of a Modest Bread, Yale University Press, 2008, p. 7

- ↑ Balinska, op. cit., p. 7

- ↑ Food Composition Tables for the Near East, Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 1982, p. 229

- ↑ Balinska, op. cit., p. 2–6

- ↑ Gillian Riley: Bread, ring-shaped, in: The Oxford Companion to Italian Food, Oxford University Press, 2007, p. 70–73

- ↑ Bre(t)z-, in: Atlas zur deutschen Alltagssprache, Universität Augsburg, Philologisch-Historischen Fakultät, 2016

- ↑ Krakelingen and Tonnekensbrand, end-of-winter bread and fire feast at Geraardsbergen, in: Intangible Cultural Heritage, UNESCO, 2010

- ↑ Fragen: Wer hat die Brezel erfunden? Und wo ist bei der Brezel eigentlich oben und wo unten?, Ulm: Museum Brot und Kunst – Forum Welternährung

- ↑ Balinska, op. cit., p. 14

- ↑ Alexander Przezdziecki: Życie domowe Jadwigi i Jagiełły: z regestrów skarbowych z lat 1388–1417, Warszawa: Skład główny w Księgarni Kommissowej Z. Steblera, 1854, p. 69–70

- ↑ Izabela Czaja, Marcin Gadocha: Obwarzanek krakowski: historia, tradycja, symbolika, Kraków: Bartosz Głowacki, 2008, p. 14–15

- ↑ Balinska, op. cit., p. 44–46

- ↑ Balinska, op. cit., p. 35

- ↑ Andrew F. Smith: Bagels, in: Savoring Gotham: A Food Lover’s Companion to New York City, Oxford University Press, 2016

- ↑ Jeremy Schneider: All 23 bagel flavors that matter, ranked worst to best, in: NJ.com

- ↑ Balinska, op. cit., p. 174–176

| ◀️ Previous | 📜 List of posts | Next ▶️ |

| ⏮️ First | 🎲 Random post | Latest ⏭️ |