Blessed Be the Food

On Holy Saturday many Polish people go to church carrying baskets of food to have it blessed by a priest. They eat this blessed food (known as ``święconka", pronounced shfyen-tsawn-kah) the next morning as part of their Easter breakfast. I once made a little poll among the Readers of the Polish version of this blog, asking them what kinds of food they put in their Easter baskets. 100% of those who responded said they filled theirs with meat products, eggs and salt. 75% added bread and other baked goods to it, while 50% included horseradish and garden crest (Poles prefer it to the closely related watercress) as well. 39% of those polled also put butter or chocolate in their baskets, 25% mentioned fruits, and only 13%, water.

What Goes in the Basket?

Alas, the sample size (n=8) didn't allow me to treat it as representative of the whole of Poland's population. So rather than conducting statistical research, let's see what information about the contents of a typical Polish Easter basket we can find in the Internet. At the end of Lent, Polish-language websites (especially those parishes, supermarket chains and web portals) fill with tips about what to put in one's basket. I took a look at a few of them.[1][2][3][4][5][6]

What I found most interesting is that all these sources not only advise their readers as to what kinds of food to place in their baskets, but also supply a kind of justification by explaining their symbolism. While various sources may differ in some details, they are overall fairly consistent. So here's my summary (you will find individual sources in the footnotes).

The foods that are always mentioned first are bread, eggs, salt and smoked meats (ham, sausage, etc.). As for their supposed symbolism, in the case of bread it's a Eucharistic and, therefore, Christian one: bread as the Body of Christ. Eggs (often brightly dyed or painted) are said to be a symbol of new or reborn life; and even though you might associate this them with Christ's resurrection, the sources avoid using the word "resurrection" itself. Salt is particularly rich in symbolic meanings: hospitality, truth, meaning of life and even immortality. The meats, we shall come back to later.

Further spots are taken by: black pepper (if mentioned, then always in the same breath as salt), lamb, cakes and horseradish. The pepper is supposedly symbolic of ``harmony between humans and nature"; cakes (especially babas, or Polish bundt cakes) stand for skill and perfection (which is why they should be always home-made), while horseradish is meant to be a sign of Christ's victory over suffering. It's getting more and more creative, I must say. When it comes to the lamb, it's not really the meat of a young sheep, but a lamb figurine, representing -- depending on the source -- Christ resurrected, victory of life over death and of good over evil, or meekness and gentleness. The figurine may fashioned out of butter, sugar, cake, chocolate or plaster (in the latter case, consumption not recommended). According to some source, you may also add cheese (possibly paskha, an delicious Easter fresh-cheese dessert, although the illustrations feature slices of yellow cheese with holes instead), butter, chocolate (probably in the form of a lamb or a bunny) and water.

What may be surprising, even shocking to some, is that many of these justifications use such verbs as "gives", "brings", "protects", "provides" or "guarantees". Apparently, the blessed victuals are not only charged with symbolic meanings, but also associated with magical properties. I've found most of such supersticious claims on the website of one Roman Catholic parish,[5] but they crop up in other sources too. And so, bread and butter are said to bring good fortune and affluence; eggs provide fertility (a chocolate bunny may have a similar effect); cold meats bestow health and fertility, and affluence! Salt and water cleanse you of your sins, horseradish makes you strong and black pepper promotes healthy growth of your livestock.

The aforementioned parish website is also unusual in that it provides a list of things you should not put in your Easter basket. I'm sure it stems from the personal experience of priests who have seen all manner of things placed in their parishioners' baskets. The website mentions a few of the most common ones that the priests consider inappropriate: bunny figurines, alcohol, toys and mobile phones.[5] Another curio comes from one major Polish web portals,[1] where Easter food-blessing tips are illustrated with a diagram of an Easter basket. Any Poles who sees it will probably ask, who puts a lit candle in their basket? It turns out, however, that the picture is a slightly modified version of an illustration which first appeared in a magazine published by the Greek Catholic Union in the United States and pertains to Easter traditions of the Carpathian Ruthenes rather than the Poles.

Benedictions

Is there a more trustworthy source that random tip from the Internet, though? I'm not sure how many churchgoers really listen to what the priest says during the ceremony of blessing their foods, but the blessing formulas he recites specify the food products that are actually being blessed. And explains why these and not others to boot! Bread and other baked goods are the first to be sprinkled with holy water.

| O Living Bread, who descended from heaven and give life to the world, bless this bread and all festive baked goods in memory of the bread with which You fed the people who were steadfastly listening to You in the desert and which You took in Your holy and venerable hands to transfigure it into Your Body. | ||||

— Obrzędy błogosławieństw dostosowane do zwyczajów diecezji polskich, vol. 2, Katowice: Księgarnia św. Jacka, 2010, p. 256, own translation

Original text:

|

So far, everything check out: bread, that is, the Body of Christ. Smoked meats come next.

| O Lamb of God, who have conquered evil and cleansed the world of sin, bless this meat, sausages and all fare which we shall consume in memory of the Paschal Lamb and the holiday foods of which You partook with Your Apostles at the Last Supper. | ||||

— Ibid., own translation

Original text:

|

Nothing about meat products magically bringing good health, fertility and affluence to those who partake of it. Only Christian symbolism related to Christ as the Lamb of God. Note that the Lamb of God is represented here not by lamb figurines made of sugar or butter, but simply by meat, even if it's pork rather than lamb.

Eggs are third to go.

| O Christ, our life and resurrection, bless these eggs, a sign of new life, so that, when we share them amidst our families, friends and guests, we could also mutually share the joy that You are with us. May we all attain Your eternal feast in Your Father’s house where You live and reign for ever and ever. | ||||

— Ibid., own translation

Original text:

|

So eggs are a sign of new life, but it's clearly linked to Christ's resurrection this time around. And that's it: only three formulas. BUt then, why do folks put salt, pepper, horseradish, sugar and so on into their baskets, if these foodstuffs are never going to be blessed anyway? Perhaps they are included in the ``and all fare" from the second blessing formula, but if so, then technically you could fill your basket if any food you want. And yet, someone or something makes people pick only a few very specific kinds of comestibles. So who or what is it? If it's not the blessing formulas, then maybe we should look into a source even more authoritative: the Holy Scripture.

“And He Took It and Ate”

The author of the Gospel of Luke took great pains to underscore that, after his resurrection, Jesus was again a man of flesh and blood, with all natural physiological needs. Having had no bite for three days, he must have been really hungry. Luke, therefore, mentions two meals Jesus had during the first day after rising from his grave. First, he met two of his disciples on their way to Emaus. They didn't recognize him, but were kind enough to invite him for supper.

| And it came to pass as he sat at the table with them, he took bread and blessed it and broke and gave to them. | ||||||

— Luke, chapter 24, verse 30; in: Jubilee Bible 2000, Bible Gateway

Original text:

|

We don't know whether anything other than bread was served.

Later that evening, Jesus paid an unexpected visit to his other disciples back in Jerusalem. He asked them two questions: first, why they looked as if they'd seen a ghost (well, duh). And just after that, the other question:

| “Have ye here any food?” So they gave him a piece of a broiled fish and of a honeycomb. And he took it and ate before them. | ||||||

— Luke, chapter 24, verses 41--43; in: Jubilee Bible 2000, Bible Gateway

Original text:

|

The honeycomb is omitted in some Biblie translations. It all depends on which ancient Greek manuscript the given translation was based on. It's hard to tell whether some scribe added that honeycomb out of his own initiative or removed it from an earlier version. In any case, there are at best only three foods we know Jesus ate that Sunday: bread, broiled fish and honey straight from the comb.

That's quite meager, but we can infer from the Gosples that Jesus had been on a rather unsophisticated diet his entire life. He mostly hung around simple fishermen on the Lake of Galilee after all and ate what they ate: bread and fish (mostly tilapia, probably), washed down with water or -- on special occasions -- with wine. Occasionally he would indulge in some simple sweets, like honey or fresh figs pilfered straight from a tree. You might think it's these few foods, sanctified by being part of Jesus's limited menu, which should take centre stage in the Easter basket. Yet none of them, save the bread, have found their way into the traditional set of Easter fare. Looks like nobody wanted to have broiled fish for the holidays after weeks of having to live on fish instead of meat throughout Lent.

A Night Different from All Other Nights

If what Jesus ate after his alleged resurrection has had no influence on the contents of Easter baskets, then maybe let us look at what he ate just before his death. In other words, what did Jesus and his disciples have for the Last Supper? The Gospels only mention bread and wine, but perhaps there were other foods on the Last Supper table, which the evangelists didn't deem important enough to note?

What was Jesus doing in Jerusalem in the first place, though? In the times when the Jerusalem Temple still stood (it was demolished in 70 CE), Jews were obligated to make a pilgrimage there at least once a year, for one of three holidays: Passover (Pesah), the Feast of Weeks (Shavuot) or the Feast of Booths (Sukkot). As a pious Jew, Jesus never failed to fulfill this obligation, even though he knew he wasn't as safe in Jerusalem as he was in his native Galilee. Eventually, during one of these pilgrimages, he ended up being charged with blasphemy, sentenced to death and executed by crucifixion; it all happened on the first day of Passover.

I've already written about how Passover combines an ancient pastoral festival of lambing ewes and a an ancient agricultural festival of new barley. I've also written about how this combination was later associated with the Biblical story of of the Jews' supposed escape from slavery in Egypt. But I haven't yet written about how Jews celebrate the eve of the first day of this seven or eight-day long holiday. On that night, ``different from all other nights", Jews gather a ceremonial supper called seder. It features seven traditional foods, each charged with some symbolic meaning, of course.

Matzah, or unleavened bread, is eaten in memory of the Jews escaping Egypt in haste and thus having no time to wait for the dought rise. Zeroa, or a lamb shank, commemorates the lambs whose blood the Jews used to smear on their doorposts as an identification marker just before the escape, as well as those later sacrificed in the Jerusalem Temple; nowadays, it's usually substituted for with a chicken wing. Beitzah, or a chicken egg that is hard-boiled and the additionally roasted, is another memento of temple offerings. Two kinds of bitter herbs -- maror and hazeret -- symbolize the bitterness of slavery in Egypt. Ashkenazi Jews (those from northern Europe) typically use romain lettuce for hazeret and horseradish (often dyed red with beetroot juice in the style of Polish beet-and-horseradish relish) for maror -- even though horseradish is neither bitter nor a herb. Haroset is a sweet paste of apples, walnuts and honey, meant to stand for masonry mortar to remember that Jewish slaves in Egypt were mostly used for contruction work. Finally, the seventh food is karpas, or some green vegetable (eg., parsley leaves) which is dipped in salted water, a symbol of the tears shed by the Jews in slavery. All of this is paired with wine.

It wasn't before the Middle Ages until this set of seder foods was fully formed, but Passover supper must have consisted of more than just bread and wine already in Jesus's times. In fact, it doesn't really matter what Jesus really ate for his last meal before death; what matters is Jews usually had for the seder around the time that the Christian custom of blessing food fro Easter was being born, which took place in the early Middle Ages. Christian priests at the time had a tendency to reuse Old Testament rituals in their liturgy.[7] And if you take a close look, you can spot some parallels between the contents of the seder table and those of the Easter basket.

Święcone ma zatem swój odpowiednik macy, z tym że przaśnik zastępuje się kwaśnikiem, czyli chlebem na zakwasie. Drożdżową babkę też można podciągnąć pod tę kategorię. Goleń jagnięcą Żydzi zastępują kurzym udkiem, a katolicy – szynką lub wieprzową kiełbasą. A także figurką baranka, żeby nie zapomnieć, że chodzi jednak o Baranka Bożego, a nie o Bożą Świnkę. Zamiast jajka pieczonego mamy w koszyku jajka barwione. Także „gorzkie zioła” uwzględnia się w święconce – pod postacią chrzanu oraz pieprzu. Rzeżuchę, na której zwykle ustawia się baranka można podciągnąć pod karpas, czyli zielone warzywo, a cukier czy nawet czekoladę można uznać za odpowiednik słodkiego charosetu. Słona woda zostaje zdekonstruowana na sól i wodę. A co z winem? To już księża zarezerwowali dla siebie jako wino eucharystyczne, surowo tępiąc umieszczanie alkoholu w koszykach do święcenia.

“Filled with Heavenly Fattiness”

Ale chwila: jak to możliwe, że ten typowo polski zwyczaj, jakim jest święcone, narodził się, zanim chrześcijaństwo w ogóle dotarło na ziemie polskie? Ano możliwe; ta i wiele innych „typowo polskich” tradycji, nie tyle zaczęły się w Polsce, ile w Polsce najdłużej przetrwały, podczas gdy gdzie indziej uległy zapomnieniu. Święcenie pokarmów odbywało się dawniej w całej chrześcijańskiej Europie. Zaczęło się już w VIII w. od święcenia, zupełnie logicznie, pieczonego baranka. Już w X w. zaczęto, oprócz baranka, święcić także inne jadło świąteczne: szynkę, ser, chleb, masło, mleko i miód. Z czasem coraz mniej się ograniczano w doborze produktów do święcenia: w XI w. doszły jajka, w XIII w. – ryby, w XVI w. – sól, chrzan, zioła, olej, drób, wino i piwo, a od XVII w. – owoce.[8]

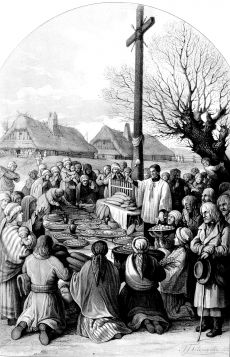

Święcenie pokarmów było doskonałą okazją, żeby pochwalić się przed sąsiadami zasobnością swojej spiżarni. Nic dziwnego, że tak dobrze przyjęło się w Polsce, w której od dawna każdego – od wielkich magnatów po bezrolnych chłopów – obowiązywała zasada „zastaw się, a postaw się”. Jedzenia nie chowało się pod serwetką w małym koszyszku, ale rozkładało na stołach i ławach, żeby było widać, ile i czego jest. Jeszcze w XIX w. oczekiwano od księży, że będą biegać od domu do domu, żeby u każdego z osobna poświęcić wszystko, co nazajutrz zamierzano zjeść na śniadanie wielkanocne.

| In our times, even those of little piety attach great weight to this ritual; everybody demands that the priest visit them personally and consider it an affront to have to bring the gifts of God to their neighbour's place. This is the case among peasants, not to mention the nobility. […] The fussiness is even greater in towns. […] Each of four indigent hirelings living together in a tight room expects her own store of food, spread on a broken stool, a cracked barrel or a crooked chest in a corner, to be blessed separately and would she ever agree to bring it into someone else's house? | ||||

— Maciej Smoleński: Cztery kościoły w ziemi dobrzyńskiej, Lwów: self-published, 1869, p. 58, own translation

Original text:

|

W zachodniej Europie zwyczaj święcenia pokarmów powoli zanikł pod wpływem reformacji. Protestanci krytykowali katolików za to, że święceniu nadawali równe, albo i większe, znaczenie jak sakramentom. Kościół zaczął więc nauczać, że jedzenie święconki nie może zastępować przyjmowania komunii w okresie wielkanocnym. W XVI-wiecznej Polsce reformacja również czyniła spore postępy, dopóki Kościół katolicki nie pokonał jej swoją kontrreformacją w wieku XVII. Luterański moralista Mikołaj Rej pisał o święceniu z przekąsem:

| On Holy Saturday, it is crucial to bless fire and water, sprinkle one's cattle with it and enchant all corners of one's house. He who doesn't eat blessed food on Easter, is not even a good Christian. […] O omnipotent Lord, is this the kind of observance you require from you poor creations? Oh, how you have always severely punished such fabulists! | ||||

— Mikołaj Rej: Kazania Mikołaja Reja, red. Teodor Haase, Cieszyn: C.K. Nadworna Księgarnia Karola Prochaski, 1883, p. 334, own translation

Original text:

|

Wróćmy na koniec do formułek błogosławieństw. Jak już wiemy, obecnie w Polsce używa się trzech, ale dawniej było ich znacznie więcej. Jeszcze w latach 60. XX w. było tych formuł siedem; w szczytowym okresie było ich ponad pięćdziesiąt[9] – osobna na każdy rodzaj pożywienia. Sól święcono jako symbol mądrości i nieśmiertelności; chrzan – jako symbol umartwienia i pokuty; mleko z miodem – jako symbol ziemi obiecanej; olej – ze względu na rzekome działanie ochronne (od chorób i grzechu); a owoce – jako nawiązanie do rajskiego owocu z drzewa poznania dobra i zła.[10] Ale chyba najważniejszą funkcją święcenia tego całego jadła i napitku było zapewnienie, by nagłe świąteczne obżarstwo po długim surowym poście nikomu nie zaszkodziło. Rej miał sporo racji, oskarżając katolików o odprawianie nad święconką czarów. Powszechne bylo przeświadczenie o magicznym działaniu obrzędu święcenia, a bodaj najlepiej o tym świadczy jeden z dawnych tekstów błogosławieństwa, w którym uprasza się Pana Boga, aby można było dobrze i tłusto się najeść, a od tego nie utyć. Czego i Wam życzę na nadchodzące święta.

| O Lord, bless this shank You have created as we call upon Your holy name, so that it is unto mankind for health and salvation, and grant that we who partake of it do not disregard Your commandments while being fattened, glutted or thickened, but that, filled with heavenly fattiness, we remain ever obedient to Your word. Through Christ Our Lord. Amen. | ||||

— Quoted in: Marian Pisarzak: Błogosławieństwo pokarmów i napojów wielkanocnych w Polsce, Warszawa: Akademia Teologii Katolickiej, 1979, p. 218–219, own translation

Original text:

|

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Martenka: Tradycyjny koszyk wielkanocny, in: Tipy, Interia, 2010

- ↑ Katarzyna Rybicka: Co włożyć do koszyczka wielkanocnego? Symbolika święcenia pokarmów, in: Garneczki.pl Blog, Poznań: Garneczki.pl, 4 April 2017

- ↑ Ewa Stopka: Z cyklu: Wielkanocne tradycje: Wielka Sobota:-) co powinno znaleźć się w koszyczku wielkanocnym?, in: Rozeta by Ewa Stopka, WordPress, 3 April 2015

- ↑ Justyna Toros: Koszyczek wielkanocny: Co włożyć do koszyczka wielkanocnego?, in: Dziennik Zachodni, Sosnowiec: Polska Press, 11 April 2017

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 To trzeba poświęcić w Wielką Sobotę, in: Parafia p.w. Św. Jadwigi Królowej w Złocieńcu

- ↑ Tradycyjny wielkanocny koszyczek, in: Tu Gazetka, Warszawa: Arbiter Media, 2018

- ↑ Marian Pisarzak: Błogosławieństwo pokarmów i napojów wielkanocnych, in: Ruch Biblijny i Liturgiczny, 46(2):93, Kraków: Polskie Towarzystwo Teologiczne, June 2003, p. 96

- ↑ M. Pisarzak (1976), s. 230

- ↑ M. Pisarzak (2003), s. 100–101

- ↑ M. Pisarzak (1976), s. 215–217, 224–225

Bibliografia

- Pesach 5782, in: Polin, Warszawa: Muzeum Historii Żydów Polskich Polin, 2022

- Marian Pisarzak

- Zwyczaj „święconego” w Kościele zachodnim, in: Collectanea Theologica, 43/4, Warszawa: Uniwersytet Kardynała Stefana Wyszyńskiego, 1973, p. 157–161

- Błogosławienie pokarmów wielkanocnych w Kościele zachodnim do wydania Rytuału Rzymskiego w 1614 roku, in: M. Rechowicz, W. Schenk: Studia z dziejów liturgii w Polsce, vol. 2, Lublin: Katolicki Uniwersytet Lubelski, 1976, p. 167–240

- Obrzędowość wiosenna w dawnych wiekach w związku z recepcją „święconego” w Polsce, in: Lud, 62, 1978, p. 53–74

- Błogosławieństwo pokarmów i napojów wielkanocnych w Polsce, Warszawa: Akademia Teologii Katolickiej, 1979, p. 218–219

- Błogosławieństwo pokarmów i napojów wielkanocnych, in: Ruch Biblijny i Liturgiczny, 46(2):93, Kraków: Polskie Towarzystwo Teologiczne, czerwiec 2003, p. 93–103

| ◀️ Previous | 📜 List of posts | Next ▶️ |

| ⏮️ First | 🎲 Random post | Latest ⏭️ |