Genuine Old Polish Bigos

The Christmas-carnival period is a time when Poles eat particularly large amounts of bigos -- assorted meats that are chopped up and stewed for hours with sauerkraut and shredded cabbage. It's a dish that you can prepare in amble quantity in advance, then freeze it (formerly, by simply storing it outside; today, in a freezer) and then reheat it multiple times, which -- it is known -- only improves the flavour. Bigos (pronounced BEE-gawss) is commonly regarded one of the top dishes in the Polish culinary canon; one would be hard pressed to name a more typically Polish food. This is how American food historian William Woys Weaver described it:

| Bigos is one of those Polish dishes that has been romanticized in poetry, discussed in its most minute details in all sorts of literary contexts, and never made in small quantities. Historically, it was served at royal banquets or to guests at meals following a hunt. It was made invariably from several types of game and served during winter. Bigos has gradually assumed the character of a Christmas and Easter dish in Poland, and today recipes are as varied and as complex as any Italian recipe for tomato sauce. In fact, some Poles even add tomato sauce to the mixture. (It does not need it.) |

| — Dembińska; Weaver (1999), p. 169 |

But is the bigos, as we know it today, really the ancient and specifically Polish dish we take it to be?

Beigießen

I'm sorry to report that etymologists agree: this epitome of Polish cuisine is referred to by a word of foreign, non-Slavic and -- what's even worse -- German origin! They are not certain, though, which German word exactly the Polish bigos derives from, but they have no doubt that some German word it is. Aleksander Brückner, a famous prewar scholar of Slavic languages, maintained that bigos comes from German Bleiguss, or "lead mold". The idea was that if you pour molten lead on water (as many Poles still do with wax for divination on Saint Andrew's Eve), you're going to get a shape that resembles bigos. Other linguists are quite unanimous in their view that this etymology makes no God-damned sense.

Suggestions that are somewhat more logical from a culinary point of view include the archaic German verb becken, "to chop", and the Old German noun bîbôz (or Beifuss in modern parlance), which refers to mugwort, a plant once used for seasoning. Others propose the Italian bigutta, or "pot for cooking soup", which supposedly entered Polish via German. But the etymology thought to be most likely is that bigos derives from bîgossen, an archaic form of the participle beigossen, from the verb beigießen, "to pour". To make a long story short, bigos is something to which someone (probably some German) has added some kind of liquid.

Minutal alias siekanka

Now, the problem is that ever since the word bigos has been used in the Polish language, it had more to do with the action of chopping than with pouring. The earliest known mention is a bigos recipe found in a herbal by Stefan Falimirz published in Cracow in 1534, entitled Of Herbs and their Potency. It was a work on medicine rather than a cookbook, so this oldest known bigos wasn't so much a dish as a medicine against "Saint Valentine's illness", or epilepsy.

| Może też, opłukawszy płuca wilcze winem czystym, potem je uwarzyć zsiekawszy na bigos i okorzenić pieprzem, imbirem, goździkami, szafranem, a to jeść przez kilka dni. Jest rzecz doświadczona na jednej białej głowie. |

| — Falimirz, Stefan, O ziołach, edited by Anetta Luto-Kamińska, Krzysztof Opaliński |

There are two interesting things we can notice here: first, 16th-century requirements regarding sample sizes in clinical studies were a lot less strict thatn they are today. And second, it was possible to make bigos without cabbage or sauerkraut. You didn't need a variety of meats either. All you needed to do to make bigos was to chop something (say, wolf lungs) up and season to make it sour, sweet and spicy.

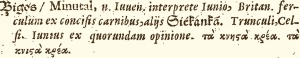

A 1621 Polish-Latin-Greek dictionary defines bigos simply as ferculum ex concisis carnibus, or "a dish of chopped meat" and provides the word siekanka ("something chopped up") as a Polish synonym. It also gives minutal as the Latin equivalent. As it turns out, Poles were not the first to enjoy sweet-and-sour chopped-meat delicacies; there were already known to ancient Romans. We can find some recipes for minutal De Re Coquinaria (On the Subject of Cooking), a cookbook that has been traditionally credtied to Apicius, but is in fact a collection of formulae from various authors compiled in the 4th--5th centuries CE. What follows is a recipe for minutal ex praecoquis, or chopped pork with apricots.

A 1621 Polish-Latin-Greek dictionary defines bigos simply as ferculum ex concisis carnibus, or "a dish of chopped meat" and provides the word siekanka ("something chopped up") as a Polish synonym. It also gives minutal as the Latin equivalent. As it turns out, Poles were not the first to enjoy sweet-and-sour chopped-meat delicacies; there were already known to ancient Romans. We can find some recipes for minutal De Re Coquinaria (On the Subject of Cooking), a cookbook that has been traditionally credtied to Apicius, but is in fact a collection of formulae from various authors compiled in the 4th--5th centuries CE. What follows is a recipe for minutal ex praecoquis, or chopped pork with apricots.

| Adicies in caccabum oleum, liquamen, vinum, concides cepam ascaloniam aridam, spatulam porcinam coctam tessellatim concides. His omnibus coctis teres piper, cuminum, mentam siccam, anethum, suffundis mel, liquamen, passum, acetum modice, ius de suo sibi, temperabis, praecoqua enucleata mittis, facies ut ferveant, donec percoquantur. Tractam confringes, ex ea obligas. Piper aspargis et inferes. |

| — Apicius, De re coquinaria, own traslation |

I've found an interesting attempt at reconstruction of this dish. The author of the Pass the Garum blog, devoted to cooking according to ancient Roman recipes, hints that you can replace liquamen, or Roman fish sauce, with store-bought Thai nam pla mixed with reduced white-grape juice; and instead of tracta, or Roman flatbread, you can use cornstarch as an equally good thickener.

And here's a Polish recipe of "Jesuit bigos" from a manuscript cookbook written at the court of princes Radziwiłł at the end of the 18th century:

| Weź pieczenią dobrą wołową przerastałą, upiecz ją pięknie, a polewaj masłem onę często. Kiedy się upiecze pięknie, pokrajać w niemałe sztuki, nakrajże cybuli niemało i smaż ją w maśle. W panew rybną piękną włóż ten bigos i cybulę. Wlejże wina kwartę, octu pół kwarty winnego, małmazjej pół kwarty. Rozynków drobnych i wielkich wsyp, limonię całą w talerzyki [plasterki] wkraj, oliwek garść, cukru przygarstnie, pieprzu wsypać, coby było dobrze korzenno, goździków całkowych kilka, pieprzu całkowego trochę, cytryny świeżej w kostkę, masła młodego łyżek dwie. Niechże wre dobrze w panwi, coby jeno trochę polewki [sosu] było. |

| — Dumanowski, Jarosław; Jankowski, Rafał, eds. (2011) Moda bardzo dobra smażenia różnych konfektów, Monumenta Poloniae Culinaria, Warszawa, Muzeum Pałac w Wilanowie, p. 139 |

Nice! As you can see, this recipe is quite similar to the Roman one, even though it calls for beer, which Polish magnates valued more than pork. Again, we've got here a fusion of sour (wine, vinegar, lime, lemon), sweet (sugar, raisins, malmsey), spicy (pepper, cloves, more pepper) and fatty (butter, olives, more butter) flavours. This combination of tastes had not changed since ancient times and can be seen in all Polish recipes for bigos (and other dishes) from that time.

What's more, not only did Old Polish bigos contain not even a soupçon of cabbage, but even meat was only optional. As long as bigos meant "something chopped up", you could make it of anything that could be chopped. So apart from veal, capon (castrated cock), wether mutton (castrated ram), rabbit, hazel grouse or beef marrow bigos, we also know recipes for carp, pike, crayfish, oyster or even crêpe bigos (or bigosek, a dimnutive form often used back then).

| Bigosek maślny z naleśnikami: Upiekłszy ich, nakrajać w siateczki i wlać wina, i octu kąszek winnego, cukru, rozynków drobnych, cynamonu i masła, i przysmażyć tego na rynce [czymś pomiędzy rondlem a patelnią]. |

| — ibid., p. 173 |

As long as you don't overdo the wine and the vinegar, then even modern children would find it palatable! By the way, one must have always been wary when it comes to vinegar. This is how Wacław Potocki warned against lack of caution when seasoning your bigos with vinegar:

Chcąc panna bigos w kuchni zaprawić co prędzej, |

| — Potocki, Wacław, Bigos w żałobie, in: (1907) Ogród fraszek, ed. Aleksander Brückner, Lwów, vol. I, p. 56, own translation |

Bigos them up!

Apart from bigos, there's also the quaint Polish verb bigosować, which means "to chop" or "to hack". And it wasn't only used in culinary contexts; it also referred to one of the favourite methods of torture and execution used by the Polish noblemen; to "bigos someone up" was to hack him to pieces with sabres. "Bigos them up!" is a call we can find in the 17th-century diaries of Jan Chryzostom Pasek and in the historical novels by Henkry Sienkiewicz that Pasek inspired. The valiant Polish nobility apparently kept abreast of times and even learned to bigos with the use of firearms, as we can see in another of Wacław Potocki's poems, where he mentions "hot bigos of lead and gunpowder".

Centuries later, Polish President Bronisław Komorowski (a historian by training) made a reference to this tradition in his famous speech to the German Marshall Fund in Washington, D.C.

| There used to be three phases of arriving at a political decision in the Polish parliament. The first phase was that of presenting views. Everyone could present any opinion they wanted. Then came the grinding phase. Grinding as in a great mortar, where you grind until you produce a uniform mass. Opinions were ground through a long-term discussion. But if this didn't help and if at least one person remained unconvinced or opposed, then he could take the floor of the Polish parliament, shout, "liberum veto!" and scurry away – thus dissolving the parliament. So the Polish nobility came up with a third phase: it was the phase of making bigos. Bigos is a peculiar dish: shredded cabbage and chopped meat stewed for a long time. So the third phase – that of making bigos – meant that the rash nobles would grab their sabres and hack him to pieces, the one who upset the government, who upset the law, before he could get away. |

| — Komorowski, Bronisław, quoted in: wPolityce.pl, 19 December 2010, own translation |

The above translation is mine, but during the actual speech, by the time the president had got to the third phase, the poor interpreter got so lost that she rendered bigosować as "stewing". Well, bigos is a kind of stew, but it didn't make any sense in this context, so I'm not sure whether the American audience ever understood this short lecture in the history of Polish cuisine and Polish parliamentarism.

Novel bigos

The 18th century introduced a kind of bigos that was a little more like the one we know today. It was made from a variety of meats, with exotic spices replaced by domestic herbs and veggies, but still no cabbage. We can find the following recipe in Kucharz doskonały (The Perfect Cook) by Wojciech Wielądko, the second-oldest fully-preserved cookbook printed in Polish:

| Veal bigos for a starter: Take some veal or other butcher's meat, or some poultry or game; you may also mix various kinds, if you do not have enough of one kind; chop it up, put in a pot together with butter, parsley, onion, chopped shallots, put on a fire, add a pinch of flour, pour in half a glass of boullion and as much [meat] juice, salt, pepper, boil for a quarter, add some coulis [thick sauce of puréed vegetables]. Serve with fried croutons. | ||||

— Wielądko, Wojciech (1783) Kucharz doskonały, Warszawa, p. 98, own translation

Original text:

|

But if you think that we're finally going to prove the Polish origin of one of Poland's most famous dishes, then think again. Wielądko didn't write about Polish cuisine; his book was a translation of La cuisinière bourgeoise by Menon. He modified the book's title to better suit his Polish readers' expectations (the cook in the original title is an urban woman, but the one in Wielądko's translation is a man of unspecified origin), but the recipes themselves remained French, even if much abridged. So does it mean that bigos is originally a French dish then? Yes and no. Wielądko simply used the word bigos as the Polish equivalent to what Menon referred to as hachis (pronounced AH-shee and derived from the verb hacher, "to chop", which is related to the English "hatchet"). We could probably trace the origins of that dish also back to the ancient Roman minutal. Minutal, hachis, salmigondis, hutsepot, hodgepodge, bigos... they all belong to one big family of chopped dishes, once featured on tables throughout Europe. Which is not surprising, if you think about it: chopping, dicing or mincing was the only way of processing meat before the first half of the 19th century, when the German inventor Karl Drais built the first meat grinder. It was only then that pâtés, sausages and fillings in the form of a uniform mass became possible.

Besides, as I've mentioned already, it wasn't only meat that was being chopped. Both in Menon's book and in Wielądko's translation we can find a recipe for a purely vegetarian dish made from diced root vegatables. Wielądko calls it "carrot-and-parsnip bigos".

| Cut onions into thin slices, brown them in butter with flour, add some bouillon, bring to boil; then add precooked and diced carrots, parsnips, celeriacs and rutabagas; salt, pepper, add a little vinegar and serve with mustard. | ||||

— Wielądko, op. cit., p. 260

Original text:

|

Przepis

A teraz pora na moją własną interpretację XVII-wiecznego przepisu na prawdziwie staropolski bigos: bez mięsa i bez kapusty! Zacząłem od tego, że pokroiłem płat dorsza na pojedyncze kęsy i zamarynowałem go w mieszaninie oliwy, octu jabłkowego, soku z limonki, miodu, cynamonu i gałki muszkatołowej. Najmniej staropolski w tym wszystkim jest prostacki miód, którego użyłem zamiast cenionego przez dawną szlachtę cukru. Następnego dnia wyjąłem go z marynaty i podpiekłem w naczyniu żaroodpornym.

W dużym woku podsmażyłem na maśle posiekaną cebulę, a następnie dodałem (uwaga!) agrest (o tej porze roku był tylko mrożony, ale akurat w tym przepisie to nie szkodzi) oraz wymoczone w porto rodzynki i suszoną żurawinę. Kiedy agrest się rozpadł, dodałem rybę i oliwki, i jeszcze trochę podgrzałem. Oliwki pojawiają się w przepisach z epoki, ale w tym wypadku bez oliwek też byłoby dobre.

Podałem (to już czysto moja inwencja) z podsmażonymi kluskami kładzionymi z mąki gryczanej i z karmelizowaną kalarepą na purée z pietruszki. Gościom powiedziałem, że to, co jedzą, to bigos; wyczuli wprawdzie, że jest w nim ryba, a nie mięso, ale byli przekonani, że czują smak kiszonej kapusty.

W kolejnym wpisie zobaczymy, jak dalej potoczyła się historia bigosu – teraz już z mięsem i z kapustą!

Bibliografia

- Dembińska, Maria; Weaver, William Woys (1999) Food and Drink in Medieval Poland: Rediscovering a Cuisine of the Past, University of Pennsylvania Press, Philadelphia

- Skarżyński, Mirosław (2017) Polish (?) Bigos: About the Thing and About the Word w: Essays in the History of Languages and Linguistics, Kraków, s. 609–617, doi:10.12797/9788376388618.37

| ◀️ Previous | 📜 List of posts | Next ▶️ |

| ⏮️ First | 🎲 Random post | Latest ⏭️ |