Epic Cooking: The Wondrous Taste of Bigos

Epic Cooking

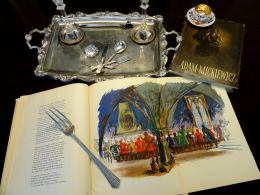

Food and Drink in “Pan Tadeusz”,

the Polish National Epic

Bigos is yum! | ||

| — Przypowieści pana Wełdysza, in: Wincenty Pol: Dzieła Wincentego Pola wierszem i prozą, Lwów: F.H. Richter, 1876, p. 360, own translation

Original text:

|

In this post I’m going to continue telling the history of bigos, the Polish national dish, and also return to Pan Tadeusz, the Polish national epic. We’ve already discussed what the protagonists of Pan Tadeusz used to have for breakfast, but what we omitted back then was the hunters’ breakfast from Book IV of the poem. That one took the form of a picnic, out in the woods, shared by a group of hunters who had just successfully concluded a bear hunt (although the bear itself was shot by Father Worm, who mysteriously disappeared a moment later).

Hunter’s Bigos

The Polish word bigos is often rendered into English as “hunter’s stew”, but in fact, hunter’s bigos, or bigos myśliwski🔊, is just one of its many varieties. Whether it’s a kind of bigos made from game meats or simply bigos eaten by hunters, but made from any kind of meat, is open to debate. As for me, I’ve never really understood why anyone would enjoy shooting terrified animals, but if Poland’s national bard himself (even if he admitted to be “a wretched marksman”[1]) wrote so much about hunting in his epic, then let’s at least quote a short excerpt, which is still quite up-to-date and may not be appreciated by the pro-hunting lobby in Poland.

The Count is well versed in the lore of the chase, | |||

| — Adam Mickiewicz: Pan Tadeusz, or The Last Foray in Lithuania: A Tale of the Gentry during 1811–1812, translated by Marcel Weyland, Book II, verses 578–591

Original text:

|

Anyway, after the hunt was over, the hunters (who had left home early in the morning with empty stomachs) treated themselves to a feast in the midst of the forest. Fires were built, “meats, vegetables, flour” and bread “were brought from the wagons”,[2] Judge Soplica “opened a box full of flagons” of Goldwasser[3] (a herbal liqueur from Danzig, or Gdańsk, famous for the gold flakes added to every bottle), while “in the pots warmed the bigos.”[4] Pan Tadeusz contains what is without a doubt the most beautiful literary monument to this Polish national dish. Or maybe bigos is considered a national dish because it is mentioned in Pan Tadeusz? Whatever the case, Mickiewicz himself admitted that he didn’t quite know how to describe what bigos actually tastes like.

Mere words cannot tell | ||

| — ibid., Book IV, verses 831–834

Original text:

|

You may remember from my previous post that sauerkraut was merely optional, and usually absent, in Old Polish bigos. In Mickiewicz’s version, though, it was already an indispensable ingredient of the recipë.

Pickled cabbage comes foremost, and properly chopped, | ||

| — ibid., Book IV, verses 839–845

Original text:

|

Rascal’s Bigos

So when, how and why did sauerkraut become part of bigos? For example, to Henryk Sienkiewicz, a turn-of-the-20th-century writer and Nobel-Prize winner, sauerkraut in bigos was so obvious that he assumed it must have been just as obvious to Lord John Humphrey Zagłoba, a character from his trilogy of historical novels set in 17th-century Poland.

“How are you, old rogue? Why twist your nose as if you had found some unvirtuous odor?” | |||

| — Translation based on Henryk Sienkiewicz: The Deluge, translated by Jeremiah Curtin, vol. 2, Warszawa: Project Gutenberg, 2011

Original text:

|

But if we moved back to the times closer to those of the trilogy’s characters, we would see that you could have eaten bigos with sauerkraut – but the kraut would have been at best a side dish rather than an actual ingredient of the bigos! Let’s take, for instance, a 17th-century epigram by Wacław Potocki about a Polish nobleman, who went empty-bellied to a banquet hosted by an Italian and returned home just as hungry. By the way, his misadventure is reminiscent of an old anecdote about a Pole who cut his stay in Italy short, because he was afraid that, if he had been treated to grass in the summer, then he would be fed hay in the winter.[5] The nobleman in Potocki’s poem, after a feast of spinach, celery, asparagus and artichokes, craved to eat his full of meat at last.

My servants have just dined. “Have you left any food?” | ||

| — Bankiet włoski, in: Wacław Potocki: Ogród fraszek, Aleksander Brückner (red.), vol. I, Lwów: 1907, p. 35, own translation

Original text:

|

Why is this funny? Because the roles were reversed and lo, the lord is having leftovers from his own servants’ table. Leftovers of what, exactly, do we have here? On the one hand, there’s the simple, rustic dish of pork fatback stewed in sauerkraut. As we can see, the idea of stewing meat and animal fat in pickled cabbage was not entirely unknown – only it wasn’t referred to as bigos! On the other hand, we’ve got something that did, in fact, go by the name of bigos and it was chopped veal that was probably seasoned sour, spicy and sweet, in line with the culinary trends of the time. This one was a more exquisite, and more expensive, dish; fit for the lordly table and known from cookbooks written at magnate courts. How did it end up on the servants’ table, then? Perhaps as leavings from their lord’s earlier meal. In this case, the hungry and humiliated protagonist would have been reduced to eating leftovers from leftovers! In the meal made from these scraps, was the sauerkraut still a separate dish that was served as a side to the veal bigos, or was everything mixed up together and reheated in a single pot? Potocki gives no answer to this question, but if it was the latter, then perhaps this is how bigos as we know it today was invented?

This is the kind of bigos that the Rev. Jędrzej Kitowicz wrote about while describing Polish alimentary habits during the reign of King Augustus III (r. 1734–1763).

| In the early part of Augustus III’s reign, there weren’t that many sumptuous dishes. There was rosół [meat broth], borscht [sour soup], boiled meat, and bigos with cabbage, made of assorted chunks of meat, sausages and fatback, chopped up finely and mixed with sauerkraut, and called “bigos hultajski”… | ||

| — O stołach i bankietach pańskich, in: Jędrzej Kitowicz: Opis obyczajów i zwyczajów za panowania Augusta III, vol. 7, Poznań: Edward Raczyński, 1840, p. 146, own translation

Original text:

|

It was called bigos hultajski🔊, or “poor man’s bigos”. Back then, the Polish word “hultaj”🔊 referred to an itinerant peasant who travelled from village to village or from town to town looking for various short-term jobs.[6] Bigos hultajski was, then, something like real bigos, as it was made from chopped meat, but of the cheaper kinds, like sausages and fatback, and it took its sour tang not from expensive limes or lemons, nor even from vinegar, but from sauerkraut or pickled beetroot juice. The sauerkraut had the additional advantage of serving as both filler and preservative. It wouldn’t take long to discover that such sauerkraut bigos could be stored for a long time and reheated multiple times, which made it a perfect food not only for itinerant peasants and domestic servants, but also for soldiers, hunters and travellers. Zygmunt Gloger, who liked to share his personal experiences in his turn-of-the-20th-century Old Polish Encyclopedia, reminisced that “in the old way of travelling, it was a superbly practical invention of Polish cuisine, which I experienced myself in 1882, when Henryk Sienkiewicz and I travelled for a few days on horseback to the Białowieża Forest.”[7]

Bigos hultajski made a stellar career not only in the culinary realm, but in literature as well – as an ideal metaphor for any kind of messy mixture of scraps which somehow manages to remain appetising. For instance, a two-act moralising romantic comedy written by Jan Drozdowski in 1801, bears the title, Bigos hultajski, or The School for Triflers (Bigos hultajski, czyli szkoła trzpiotów).

As in food, so in life, there must come the hour | ||

| — Jan Drozdowski: Bigos hultajski, czyli szkoła trzpiotów, Kraków: Jan Maj, 1803, p. 60, own translation

Original text:

|

Bigos hultajski also makes an appearance in the title of a four-decades-younger novel by Tytus Szczeniowski (published under the nom de plume Izasław Blepoński), Bigos Hultajski, or Social Poppycock (Bigos hultajski: Bzdurstwa obyczajowe). It’s not really a novel in the modern sense, but rather a loose collection of stories, drafts, digressions, polemics and sociological conjectures, arranged into a plot without a beginning or an ending. Apparently, the only thing the binds its four volumes together is a series of four forewords (and one “hindword”), which are incidentally considered the most interesting parts of the entire work.[8] This is what the author wrote of his own novel in the foreword to the first volume:

| This novel is a messy mixture of everything, […] just a scaffold thrown to the wind, to hold images haphazardly hung thereupon […] All bizarrely entangled and without any logic […] Such will be this book, full of repetitions, chatter and descriptions that fell off the pen wherever they happened to be nudged by my imagination; this is why I’ve entitled it “Bigos Hultajski”, which is made from a variety of things. It’s a poor man’s dish, but a savoury one; and perhaps it will be said of this novel that it is a poor man’s roman and an unsavoury one. | ||

| — Izasław Blepoński: Bigos hultajski: Bzdurstwa obyczajowe, Wilno: Teofil Glücksberg, 1844, p. XVII–XVIII

Original text:

|

With time, the word “hultaj” gained a negative connotation that it has today. In modern Polish, it’s roughly equivalent to the English “rascal”. The origin of the term “bigos hultajski”, now understood as “rascal’s bigos”, was largely forgotten. Gloger hypothesised that “because the best bigos contains the greatest amount of chopped meat, then there is a certain analogy with rascals, or brigands and highwaymen, who used to hack their victims to pieces with their sabres.”[9] And so even today we can find explanations, as in Polish Wikipedia, that bigos hultajski is a kind of bigos that is particularly heavy on meat and not – as in its original sense – a dish in which the scarcity of meat was masked with sauerkraut.

By the time Mickiewicz wrote Pan Tadeusz, which was in the early 1830s, bigos hultajski must have become so popular that it supplanted all other, older, kinds of bigos. Then it could finally drop the disparaging epithet and become, simply, bigos. No self-respecting Polish cookbook writer of the 19th century could neglect to include a few recipës for sauerkraut bigos in her works – including the great (both figuratively and literally) Lucyna Ćwierczakiewiczowa. Below, I quote a recipë written by one of her most loyal fans – Bolesław Prus (today remembered as a great novelist and somewhat less remembered as a columnist).

| Even if our planet is graced by many sentient beings who are not unfamiliar with the pleasures of bigos, there are still (alas!) few mortals who have fathomed the art of preparing this stew. How, then, is it done? Thusly. On the first day, cook sauerkraut and meat separately. On the second day, combine the cooked sauerkraut with chopped meat; this is but a scaffold for a future bigos, which dilettantes consider to be true bigos already. On the third day, reheat the mixture, miscalled bigos, and douse it with grape juice. On the fourth day, reheat the substance and add some bouillon and a tiny bottle of steak sauce. On the fifth day, reheat the mixture and sprinkle it with pepper in a grenadier manner. By this point, we’ve got some juvenile, fledgling bigos. So, to make it mature and strong, on the sixth day, reheat it; on the seventh day, reheat it – and – on the eighth day, reheat it. But on the ninth day, you’ve got to eat it, because, on the tenth day, classical gods, attracted by the scent of bigos, may descend from the Olympus to snatch this delicacy away from the mouths of mortals! | ||

| — Bolesław Prus: Kronika tygodniowa, in: Kurier Warszawski, 285, 1879,[10] own translation

Original text:

|

In the end, this whole elaborate and gripping recipë turns out to be just a lengthy introduction to a piece on a totally mundane and non-culinary topic.

| To reheat, toast and reheat again is a method which adds splendid characteristics to things of this world. One of such things that may be reheated over and over, forever, is the question of Warsaw’s sewer system. | ||

| — ibid.

Original text:

|

Hard-to-Digest Bigos

Unfortunately, not everything that tastes good is good for your health. Bigos happens to have a reputation for being an excessively high-fat dish that tends to sit heavy on the stomach. What’s more, it is usually made from leftovers, which has often aroused suspicions as to the freshness of its ingredients. You can see it, for example, in The Good Soldier Švejk by the Czech writer Jaroslav Hašek, where, on the one hand, one should be glad that “bikoš cooked in the Polish way” made a career as an important part of the Austro-Hungarian army’s diet on the Galician front, but, on the other hand, it was accused by Lieutenant Dub of giving him diarrhoea.

| Before they got to Żółtańce, Dub stopped the car twice and after the last stop he said doggedly to Biegler: “For lunch I had bigos cooked the Polish way. From the battalion I shall make a complaint by telegram to the brigade. The sauerkraut was bad and the pork was not fit for eating. The insolence of these cooks exceeds all bounds. Whoever doesn’t yet know me, will soon get to know me.” | |||

| — Jaroslav Hašek: The Good Soldier Švejk and His Fortunes in the World War, translated by Cecil Parrott, Penguin Books, 2005, p. 746

Original text:

|

The good thing is that, as the Poles discovered long ago, fine Polish vodka not only pairs ideally with the stew, but is also an indispensable antidote to bigos-induced indigestion.

One of the nobles brought bigos to share. | ||

| — Jan Nepomucen Kamiński: Przypadek na odpuście, Lwów: Biblioteka Uniwersalna, 1881, p. 7, own translation

Original text:

|

And because, as mentioned above, bigos was often taken as provisions for a journey, it was just as important to take an adequate amount of vodka along as well. After all, health should always come first!

| In the meantime, Gaudentius, who hadn’t failed to provision himself for the journey with leftovers from the feast of Yasnohorod, was busy reheating and consuming bigos, generously seasoned with sausages and fatback, which he had retrieved from his coffer, and washing it down, in strictly calculated intervals, with ample doses of vodka, which he kept by his right-hand side in a large rectangular decanter. […] Bigos, as is known, induces great thirst, which had to be quenched with a concoction of some kind; nearby, at Finke’s, this and other “remedies” were at hand for savouring. This venture, undertaken with certain tact, yet amateurishly, took quite some time; it had been over an hour since the sun had hidden below the horizon, when Mr. Pius was still exorcising the effects of the greasy bigos with last drops from the last bottle. | ||

| — Obrazek Jenjalnego Officjalisty, in: Franciszek Marian Ejsmont: Co Bóg dał, Kijów: Drukarnia Uniwersytecka, 1872, p. 305–306, own translation

Original text:

|

So to sum up: there’s a dish that is tasty, yet hard to digest and made from ingredients of questionable quality. Let’s add significant potential for figurative use and an undeniable status as a national dish. What do we get? That’s right – bigos as a metaphor for Polish history, society, politics, and Polishness in general!

| History is like bigos, an indigestible hodgepodge of scraps, not just from the whole week, but from thousands of years. | ||

| — Kornel Makuszyński: Szatan z siódmej klasy, Warszawa: Instytut Wydawniczy Nasza Księgarnia, 1985, p. 7, own translation

Original text:

|

National Bigos

Cyprian Kamil Norwid, a great poet of the second half of the 19th century, was able, in just one short poem, to mock both the national stew and the parochial mindset of Polish gentry, whose minds – like bigos – were just messy mixtures of diced-up thoughts.

What you write of bigos, the national stew, | ||

| — Cyprian Kamil Norwid: Z listu do Henryka Prendowskiego, Wikiźródła: Wolne materiały źródłowe, own translation

Original text:

|

Mr. Ernest Bryll, a 20th-century poet, gave an even more direct answer to the question of what to write of the national bigos. He thinks of it as a “dangerous, heavy dish, […], a mixture of everything, but also hacking people to pieces”.[11] It’s the dark side of bigos, reflecting the dark side of Polish history.

What to write of bigos, the national stew? | ||

| — Ernest Bryll: Co o bigosie pisać?, Oficjalna strona Ernesta Brylla, own translation

Original text:

|

A less poetic, but no less colourful bigos metaphor was employed by Prime Minister and Minister of Military Affairs, Marshal Józef Piłsudski, when criticising the state of Polish interwar democracy. Once again, we’ve got here bigos of the smelly, unhealthy kind, cooked from unfresh ingredients…

| As you can see, the constitution is as unbalanced and vague, its language as sloppy, as sloppy are the minds of the MPs. On a general note, I’ve got to tell you that this sloppy language makes our constitution somewhat akin to paltry bigos made from rotten ham, half-rotten fatback and half-cured sauerkraut; so that each paragraph and article may and should be read completely on its own, without linking it with any other article. Naturally, the rotten ham is for the president, the half-rotten fatback is for the cabinet, and the parliament is left with the half-cured sauerkraut. As you can see, there’s nothing their stomachs can do about it and what comes out is stench, so that it reeks all along Country Street [ulica Wiejska, where the Polish parliament is located]. And the only way out of this chaos is to rewrite the constitution in a decent way. What’s more, nobody has the right to interpret the constitution. Interpretation is forbidden – so the government is left with nothing but bigos. | ||

| — I wywiad Miedzińskiego (26 sierpnia 1930 r.), in: Józef Piłsudski: Pisma zbiorowe, vol. IX, Warszawa: Instytut Józefa Piłsudskiego, 1937, p. 219-220, own translation

Original text:

|

For good or ill, bigos seems to fit the Polish soul and Polish history so well that you can feel Makuszyński’s disappointment when he realises that another dish will make a better metaphor of a phenomenon he just observed in Polish society.

| So far, I’ve been under the false impression that the Polish national dish was bigos, an exquisite stew of cabbageheads, bitter hearts and virulent liver, a dish full of sourness and pungent smells. Someone would always “cook bigos” [i.e., make a mess] for someone else, then they would slap one another in the face, in a newspaper or in a café, and life, replete with rosy cheeks, temperament and fulsomeness, was beautiful. It saddens me, though, to see that tradition is fading away, as is the noble dish of bigos, and it is the Polish-style beef tongue that now reigns supreme on the Polish menu. Bigos was an exuberant dish, announcing itself through its scent from afar, juicy and vigorous. Tongue in the Polish style is more intricate, sweetened with almonds and raisins; it is, indeed, the dumbest part of a thoughtless beast, but the sweetness of its seasoning is ineffably appetising. | ||

| — Kornel Makuszyński: Ozór po polsku, in: Świat, 22 (7), Warszawa: Wydawnictwo Orgelbrandów, 12 February 1927, p. 3, own translation

Original text:

|

Three-Cheer Bigos

And now it’s time for a little curiosity. Have you ever heard of bigos z wiwatem🔊, or “bigos with a cheer”?

| Hunter’s bigos was served at hunts, as well as bigos with a cheer (pre-cooked bigos was reheated in a pot whose cover was tightly sealed with dough; a loud “explosion” of the lid due to pressure was a sign that the bigos was ready). | ||

| — Magdalena Kasprzyk-Chevriaux: Historie kuchenne: Nie od razu z kapustą bigos gotowano, in: Wyborcza.pl, Agora, 16 January 2016, own translation

Original text:

|

That would be some loud cheer! But an even greater curiosity is that, while you can find quite a few descriptions of this tradition on the Internet (mostly in Polish, though), they all sound quite similar (usually not longer than one or two sentences) and, what’s more, none of them cites any sources of this information. Surely, if it’s really a time-honoured tradition it is claimed to be, then it must have been mentioned in some old books, right?

However, I’ve been unable to find any mention of the “bigos with a cheer” in pre-Internet sources. You could say, of course, that I could have asked some of those people who wrote or talked about it. Well, I tried, but to no avail. It would turn out that either the source has escaped that person’s memory or that it’s simply a fact so obvious that no citations are necessary. Besides, you can find information about bigos with a cheer everywhere, I’ve been told; just grab any 19th-century cookbook that comes to hand. Well, it is true that old recipës do mention a method of cooking where the pot is sealed with dough. Ćwierczakiewiczowa advises to cook the “English meatloaf” in such a way,[12] while Maria Gruszecka uses this method to prepare a “meat essence” for the sick.[13] But still no sight of bigos cooked in a sealed pot, let alone a recipë where a lid blowing off the pot would be a desired effect rather than accident. Nor was I able to find the phrase “bigos z wiwatem” anywhere I looked.

What I did discover was that this peculiar kind of bigos not only doesn’t seem to be mentioned in pre-Internet sources, but it’s also absent in online sources that are older than 26 November 2006. So what happened on the particular day? This is when Tomasz Steifer, a painter and heraldist, added the following information to the “Bigos” article in Polish Wikipedia:

| Old Polish cuisine, especially at hunts, knew bigos with a cheer, in which the pre-cooked dish was reheated in a pot with its cover tightly sealed with dough. A loud “explosion” of the cover caused by the pressure meant that the dish was ready for consumption. | ||

| — Bigos, in: Wikipedia: wolna encyklopedia, 26 November 2006, own translation

Original text:

|

No citation here either and so it has been to this day. I can tell you, as a long-time Wikipedian myself, that any information you find in Wikipedia is worth only as much as reliable is the source given in the citation. And if there’s no citation at all? Well, there you go. Yet Wikipedia’s reputation is so good that this factoid has quickly spread through the Polish web. Did Mr. Steifer read it in a book I haven’t been able to lay my hands on, did he describe an anecdote he had once heard, a family tradition, or did he take it simply out of his own head? This we may never know, as Tomasz Steifer died in 2015.

It’s possible, of course, that the source does exist and that this quaint method of cooking bigos was actually practised. So if you remember having read about it somewhere, then I will be very grateful for a bibliographic reference. Or maybe you prepare bigos in this way yourself and would like to share your personal experience with cheering bigos in the comment section below?

The only recipë I’m aware of that could be described as “bigos with a cheer” (although this appellation is not used in the source) is a hint, given by Castellan Adam Grodziecki in his 17th-century manuscript, for a rather bawdy and somewhat primitive prank. It’s bigos with a cheer that you can smell!

| Mix some ant eggs […] into bigos […] or anything else, […] so whoever eats it, the bench underneath him will surely creak and it will go into your nose. | ||

| — Adam Grodziecki: Miscellanea De Omniscibili ex Observationibus, Biblioteka Kórnicka Polskiej Akademii Nauk, manuscript 711, f. 122; quoted in: Jarosław Dumanowski: Staropolskie przepisy kulinarne: Receptury rozproszone z XVI–XVIII w.: źródła rękopiśmienne, Warszawa: Muzeum Pałacu Króla Jana III w Wilanowie, 2017, p. 314, own translation

Original text:

|

Whether it’s actual ant eggs or a folk name for the seeds of some carminative plant, is not certain. Prof. Jarosław Dumanowski suspects that “ant eggs” may refer to common knotgrass.[14]

Finally, let’s return to Pan Tadeusz one more time, because I’ve also come across the argument that “bigos with a cheer” is mentioned in this epic poem. Indeed, the words “bigos” and “wiwat” (“cheer” or “hurrah”, from Latin “vivat”, “long live”) even appear in the same verse. But who’s doing the cheering here – and three times at that? Is it the lid (loudly blowing off) or the hunters raiding the pot (cheering out of joy that the bigos is ready)? I will let you read and decide for yourself.

Now the bigos is ready. With triple hurrah | ||

| — Mickiewicz, op. cit., Book IV, verses 846–850

Original text:

|

Recipë

As quoted above, Henryk Sienkiewicz and Zygmunt Gloger enjoyed bigos in 1882, while travelling to the vast primaeval Białowieża Forest in what is now eastern Poland. In 2015, two hairy Englishmen, David Myers and Simon King, relived this experience, except they rode motorbikes instead of horses. Here’s a video of them cooking bigos (which, for some reason, they pronounce “bigosh”) in the midst of the same forest.

References

- ↑ Mickiewicz, op. cit., Book IV, verse 43

- ↑ Mickiewicz, op. cit., Book IV, verses 820–821

- ↑ Mickiewicz, op. cit., Book IV, verse 821

- ↑ Mickiewicz, op. cit., Book IV, verse 831

- ↑ Jan Stanisław Bystroń: Dzieje obyczajów w dawnej Polsce: wiek XVI–XVIII, Warszawa: Księgarnia Trzaski, Everta i Michalskiego, 1933, p. 473

- ↑ Witold Doroszewski: Słownik języka polskiego, Warszawa: Państwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe, 1958–1969

- ↑ Zygmunt Gloger: Encyklopedia staropolska, vol. I, Warszawa: P. Laskauer i W. Babicki, 1900, p. 173, own translation

- ↑ Lucyna Nawarecka: Bigos romantyczno-postmodernistyczny: O przedmowach Tytusa Szczeniowskiego, in: Romantyczne przemowy i przedmowy, Katowice: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Śląskiego, 2010, p. 215–217

- ↑ Gloger, op. cit.

- ↑ Cyt. za: Bolesław Prus: Kroniki, oprac. Zygmunt Szweykowski, vol. 4, Warszawa: 1958, p. 90–91; cyt. za: Agnieszka M. Bąbel: Garnek i księga – związki tekstu kulinarnego z tekstem literackim w literaturze polskiej XIX wieku, in: Teksty Drugie, 6, Warszawa: Instytut Badań Literackich Polskiej Akademii Nauk, 2000, p. 178–179

- ↑ Ernest Bryll: Co o bigosie pisać? – odpowiedź czytelniczce, Oficjalna strona Ernesta Brylla

- ↑ Lucyna Ćwierczakiewiczowa: 365 obiadów za pięć złotych, Warszawa: Gebethner i Wolff, 1871, p. 71

- ↑ Maria Gruszecka: Ilustrowany kucharz krakowski dla oszczędnych gospodyń, ed. 9, Kraków: Księgarnia J. M. Himmelblaua, 1897, p. 30

- ↑ Dumanowski, op. cit.

| ◀️ Previous | 📜 List of posts | Next ▶️ |

| ⏮️ First | 🎲 Random post | Latest ⏭️ |