A Fried Pie and a Fish Dish

Szczecin – formerly known by its more pronounceable German name, Stettin – is a port city in northwestern Poland and home to two peculiar snacks. They’re called pasztecik szczeciński and paprykarz szczeciński, pronounced: pash-TEH-cheek shcheh-CHEEN-skee and pahp-RIH-kash shcheh-… oh, you know what, never mind, forget it; let’s just call them PS1 and PS2, alright?

PS1 is a kind of hand-held deep-fried pastry filled with ground meat or some other stuffing. On 20 October, Szczecinians celebrated the PS1 Day – a tradition that dates all the way back to 2017. As far as I know, this treat is virtually unknown anywhere in Poland outside Szczecin itself. PS2, on the other hand, is a canned fish spread that is popular throughout the country. It doesn’t seem, however, to have its own holiday yet.

When it comes to Szczecin – or western Polish borderlands in general – it’s difficult to speak of any long-held culinary traditions. The Germans took with them any local traditions that might have been here prior to World War 2 – either to western Germany or to mass graves. The territories vacated by the expelled Germans and annexed by Poland in 1945 were then resettled by people from Poland’s eastern borderlands that had been ceded to the Soviet Union. This way Poland literally shifted westwards and old recipes brought from Poland’s former East became the foundation for a new culinary culture in Poland’s new West. In Szczecin, people built atop this foundation, adding such novelties as Soviet army inventions, exotic recipes brought by sailors and fishermen from overseas, and – more recently – attempts at reconstructing old German local specialties (such as the Stettin gingerbread).

Mr. Adam Zadworny, a Szczecin-based journalist, has written much about the history of PS1 and PS2. Sometimes it’s difficult to tell what in his articles is true, what is an error and what is a myth. When he writes that East German tourists were taking PS1 from Szczecin back home across the Oder (even though downtown Szczecin lies on the Oder’s west bank) or that Alaska pollock and blue grenadier are Atlantic fish species (when, in fact, they live in the Pacific), then we know he just didn’t do his homework diligently enough. It’s when it gets even more confusing that we know we’re going to have some fun.

PS1 (pasztecik szczeciński)

PS1’s are actually Russian pirozhki mass-produced in a special pirozhki-frying machine, called AZhZP-M, which has been developed by the Red Army and is still manufactured in a Ukrainian arms factory. The first such machine, from army surplus, appeared in Szczecin in 1969. Pirozhki may be easily confused with Polish pierogi, even as they have little in common apart from the basic idea of wrapping some kind of filling with dough and both their names coming from the Proto-Slavic word *pir, meaning “a feast”.

So when AZhZP-M started to churn out freshly-fried pirozhki in a Szczecin coöperative fast-food bar, they had to be given a new name. The bar’s management settled for the word pasztecik, which means “a little pie” in Polish. By the way, the machine is still operational, making PS1’s at Al. Wojska Polskiego 46 (46, Polish Army Avenue) in Szczecin. Soviet-built machines were made to last.

AZhZP-M is a big metal box weighing almost a tonne, with two cylindrical containers attached to it. One contains yeast dough, the other contains filling. The contents of both are pushed out through tubes so that the filling is encased by the dough; the machine cuts out equal lengths to form little oblong pies. They are placed on a special metal cradle that travels inside the box; there, the pies first rest for a while and then get dunked in a tub of hot oil. After 40 minutes, fresh PS1’s fall out of the box – one every four seconds on average.

Mr. Zadworny does not provide the name of the constructor of this ingenious invention. The details of its manufacture, which belonged to Soviet arms industry, have always been classified as a military secret. Or so, at least, claims the journalist, for whom the secrecy may just be a perfect excuse for not digging any deeper.

| [In November 1991] a certain Szczecin-based businessman was hoping to make lots of money importing the machines. However, he didn’t know where to buy them. He only knew the name of the Soviet factory located somewhere in the Ukrainian SSR. He travelled to the Soviet Union and eventually found the town where the factory was located. He asked for its address in the streets, but people just shrugged him off. When he finally found it and started a conversation with the gatekeeper, he got arrested by the KGB. The officers who questioned him were surprised to find that he was looking not for military secrets, but for a pirozhki-making machine. He was released after a few hours, but failed to strike a deal. The factory was as big as the Szczecin shipyard and – as it turned out – was manufacturing ICBM parts, among other things. The pie-frying machines were being made in just a single old factory hall. | ||||

— Adam Zadworny: Awtomat do prigotowlenia pierożkow, in: Gazeta Wyborcza, 45, Szczecin: Agora, 22 February 2002, p. 6, own translation

Original text:

|

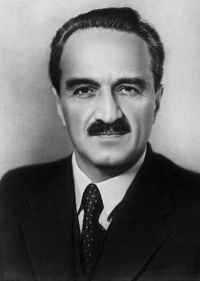

What we do know is the name of the man at the top echelons of Soviet power who was responsible for promoting this kind of gastronomical solutions. It was Anastas Mikoyan, the only Soviet dignitary who became member of the Central Committee in Lenin’s time, survived all the purges of the Stalin era, continued his career at Khrushchev’s side and peacefully retired under Brezhnev. In 1935, as minister of foreign trade, he travelled for a three-month visit to the United States where he was fascinated by the great progressive convenience available to working people – the American fast food. Back in the Soviet Union, he set about establishing a network of communal feeding establishments to liberate women from “kitchen slavery”. For the first time, the Soviets could sample their localized version of hamburgers (known as Mikoyan cutlets), popcorn and corn flakes, ice cream cones and other western delicacies.

The eating habits that Mikoyan promoted – as you can see in the title of the book published on his initiative, The Book of Healthy and Tasty Food – were a marriage of modern, rational nutrition with the traditional cookeries of the Soviet Union’s ethnic groups. The way food looks and tastes became as important as its nutrients and calorific value (a novel approach in communist thinking about food), even if many people bought the book only to marvel at the full-page colour illustrations and dream about such luxuries as sturgeon in aspic. The pirozhki-making machine, producing tasty and cheap food in large quantities, was ideally suited to fit in with this trend.

After World War 2, these ideas found their way into Poland. Recipes for bread, sausage and vodka were standardized, vocational culinary schools began to teach the principles of rational alimentation, milk bars started to pop up in cities across the country. Mikoyan personally visited the workers’ cafeteria at the steel mill in Nowa Huta. And in Szczecin, the first AZhZP-M machine was placed in the window of a fast-food bar, to let passers-by observe the production process and encourage them to come inside. The PS1’s were filled with ground meat – beef at the end of the Gomułka era (roughly, the 1960s), pork under Gierek (70s), eventually replaced with vegetarian fillings during the food shortages of the Jaruzelski era (80s). Today, the PS1’s are available in many variants: meat, sauerkraut and mushrooms, egg paste, farmer cheese and sugar. There’s more than one PS1-making machine in Szczecin now and on the Internet you can easily find more used AZhZP-Ms for sale, offered in Russia, Ukraine, Belarus or Kazakhstan. In these Russian-language offers one can read that the best filling is made from liver, but dried apricots are also good. I wonder what Szczecinians would have to say to that.

PS2 (paprykarz szczeciński)

PS2 is a reddish-brown canned fish spread made from rice, tomato paste, vegetable oil and some fish, seasoned with onions, salt and spices. A favourite of Polish hikers and students, it’s one of those canned foods you would never put in your mouth at home, but somehow becomes a beloved snack on an outdoor excursion. Its production in Szczecin began at about the same time as the arrival of the first PS1 machine. Wojciech Jakacki, production manager at Gryf (Griffin), a Szczecin-based state-owned far-sea fishing and fish processing company, is credited as the author of the original recipe for PS2. Back in the 1960s, the company’s far-sea fishing activity was located off the coast of West Africa. This is how Gryf’s founder, Mr. Bogusław Borysowicz, remembers where Jakacki drew his inspiration from:

| One day, technologists from our freezer trawlers sampled a local delicacy called “chop-chop” in one of the ports. It contained fish, rice and a very hot spice called “pima”. Back in Poland, Jakacki asked the lab girls, if they could try and develop something similar that could be canned. And after many trials and errors, they succeeded. This is how our paprykarz was born. | ||||

— Borysowicz Bogusław, quoted in: Adam Zadworny: Kultowa puszka Gryfa, in: Gazeta Wyborcza, 271, Szczecin: Agora, 21 November 2003, p. 6, own translation

Original text:

|

Now the problem is, I couldn’t find any mention of, let alone a recipe for, this supposed West African “chop-chop” dish. A spice by the name “pima” does not exist either (I mean, it doesn’t exist on the Internet, but that’s as good as not existing at all). Did Mr. Borysowicz misremember the names? Or did he repeat names that had been already butchered by the Gryf fishermen? In West African Pidgin English, the word chop means simply “food” or “to eat”. So is it possible that the fishermen were treated to a local delicacy by someone who encouraged them by saying, “eat food”, and the Poles took it to be the name of the dish? If we want to identify it, we may have to try a different approach.

Instead of searching by the name, let’s try to search by ingredients. Is there a West African dish made from rice, fish, tomato paste and hot spices? Yes, it turns out there is! It’s the national dish of Senegal, also popular in other West African countries, which goes by the name spelled ceebu jën in Wolof and thiéboudienne in French; it’s pronounced roughly cheh-BOO-djen and means simply “rice with fish”. To make it, you take an Atlantic fish called dusky grouper, cut it into steaks and stuff each one with finely chopped parsley, onion and garlic. Then you sauté vegetables (onion, chili pepper, potatoes, African eggplant, okra) with tomato paste and possibly a dried sea snail called Cymbium olla (also known as “Senegalese camembert” due it its pungent smell). Then you add water and cook the fish steaks in this soup. Once it’s cooked, you remove the fish and the veggies from the pot and replace them with some rice to let it absorb all of the broth. The fish and the veggies are served on the rice.

Okay, and what about the “pima”? This happens to be quite easy: the mysterious spice appears to be nothing more than a Polish phonetic spelling of piment, the French word for a chili pepper.

But how much in common does the Senegalese dish of large chunks of fish and vegetables served on a bed of rice have with the Polish can filled with a “firm paste” that may be “juicy” or “slightly dryish” and whose surface may be covered with “a film of oil” (the quotations are from the website of the Polish Ministry of Agriculture)?

Well, the birth of PS2 is directly linked to an efficiency improvement project whose goal was to find some use for the scraps left over from cutting large blocks of frozen fish on Gryf’s freezer trawlers. Forget about entire steaks, which wouldn’t have fit into the cans anyway. The cans were packed with finely ground fish scraps (sometimes with fins, scales and all) and Bulgarian tomato pulp; only rice grains were visible with a naked eye.

The mixture of overcooked flesh, hot spices and onions must have reminded someone in Szczecin of the Hungarian paprika-seasoned stew called paprikás. Although I must point out that, technically, paprikás must, by definition, contain sour cream; without sour cream, it is pörkölt. And you should never confuse either of these with goulash; in Hungary this is a soup rather than a stew (its name comes from the Hungarian word gulyás, or cattle herder, so it may be translated as “cowboy’s soup”). In any case, this is how PS2 got its name, "Szczecin paprikash".

All in all, we can say that PS2 is a Polish mashup of Senegalese and Hungarian culinary traditions, which means that Szczecinians were making extreme fusion cuisine before it was a thing! After the fall of communism, Polish far-sea fishing business became economically unsustainable and Gryf went bankrupt. But, as PS2 was never trademarked, it soon started to be produced all over Poland – often from freshwater fish. The labels often say vaguely that the spread contains “spices”, so there may be no paprika among its ingredients at all. Just like the Holy Roman Empire was, according to Voltaire, neither holy, nor Roman, nor an empire, so is today's “Szczecin paprikash”, made neither in Szczecin, nor from paprika.

Recipe

Writing about food made me hungry, so I decided to do some cooking. I tried to make my own take on ceebu jën. For want of certain ingredients, I had make do with some substitutions. As the Polish fishing fleet no longer operates off the coast of Senegal, I’ve used Alaska pollock instead of the dusky grouper. And because it was cut into fillets, and not steaks, I had to simply smear it on all sides with the filling, which I made by blending parsley with two onions and a few garlic cloves). Then I also sprinkled the fish with smoked paprika and some herbal olive oil.

As for the veggies, I’ve used tomatoes, a large carrot, an eggplant (a regular one, not an African one) and two sweet potatoes (instead of regular ones, as I wanted something slightly more exotic). All this I boiled in water with tomato paste, then I removed the veggies and put the fish in their place.

Once the fish was done, I removed it as well, and put risotto rice into the broth. When the rice was done, I sprinkled it with some gumbo filé to take up the excess moisture. Gumbo filé, or ground dried sassafras tree leaves, is as unobtainable in Poland as okra, but I still have a few jars that I bought once in the United States.

I saw on YouTube that the way to serve ceebu jën is to place the fish on a bed of rice and surround it with the vegetables. And how does it taste? Let me just say this: it’s better than PS2.

| ◀️ Previous | 📜 List of posts | Next ▶️ |

| ⏮️ First | 🎲 Random post | Latest ⏭️ |