Difference between revisions of "Even Older Polish Cookery for Complete Beginners"

| Line 191: | Line 191: | ||

| wolumin = 20 | | wolumin = 20 | ||

| strony = 22–42 | | strony = 22–42 | ||

| − | }}</ref> But hold, you may | + | }}</ref> But hold on, you may say, why the Manuscript Institute? We're talking about a printed book, aren't we? Well yes, but keep in mind what we said about culinary recipes being contantly copied and rewritten. Back when nobody kept a smartphone equipped with a camera and an OCR function in the pocket -- back when even photocopiers didn't exist -- people commonly copied recipes they found in printed sources by hand. Sometimes they would even create entire manuscript cookbooks that were compilations of recipes taken from diverse sources, both printed and handwritten. It was one such manuscript, entitles ''Zbiór dla kuchmistrza, tak potraw jako ciast robienia'' (''A Collection for a Master Chef, of Recipes for Both Dishes and Cakes'') cookbook that caught Dr. Bulatova's attention and led her to get in touch with the foremost specialist on the history of Polish cuisine, Prof. Jarosław Dumanowski at Copernicus University in Toruń. |

The manuscript contains a total of a about a thousand recipes, as well as medical, veterinary and gardening tips -- all written by the same hand. The sources these recipes and tips were gleaned from are not always indicated in the text, but you can see from the different styles and grammars that they must have originated in various historical periods -- mostly within the 16th and 17th centuries. And yet, the copyist who made the manuscript clearly indicated on the title page that he finished his work on 25 July 1757 (such dating is further borne out by water marks found on the paper). Which means by the time the manuscript was created, the recipes which were copied into had already been quite old. The copyist himself didn't sign his work, but the book's first owne left her signatures on three different pages. It was Rozalia Pociejowa ''née'' Zahorowska (ca. 1690–1762), a prominent noblewoman living from Volynia in what is now western Ukraine. What led her to commission such a compilation of recipes from previous centuries? Did she wish to study culinary history? Or maybe these old recipes still seemed relevant to her own times and she saw the collection in purely practical terms? We don't really know. | The manuscript contains a total of a about a thousand recipes, as well as medical, veterinary and gardening tips -- all written by the same hand. The sources these recipes and tips were gleaned from are not always indicated in the text, but you can see from the different styles and grammars that they must have originated in various historical periods -- mostly within the 16th and 17th centuries. And yet, the copyist who made the manuscript clearly indicated on the title page that he finished his work on 25 July 1757 (such dating is further borne out by water marks found on the paper). Which means by the time the manuscript was created, the recipes which were copied into had already been quite old. The copyist himself didn't sign his work, but the book's first owne left her signatures on three different pages. It was Rozalia Pociejowa ''née'' Zahorowska (ca. 1690–1762), a prominent noblewoman living from Volynia in what is now western Ukraine. What led her to commission such a compilation of recipes from previous centuries? Did she wish to study culinary history? Or maybe these old recipes still seemed relevant to her own times and she saw the collection in purely practical terms? We don't really know. | ||

Revision as of 20:23, 1 May 2024

I once wrote here about old Polish recipës that were both extremely easy to cook and surprisingly modern, which made them perfect for people who were only starting to try their hand at historical culinary reënactment. We could see how a recipë's simplicity could also mean its durability; scrambled eggs, for example, are still prepared in much the same way as they were two hundred, four hundred or one thousand years ago.

I took the recipës from Compendium Ferculorum (A Collection of Dishes) by Stanisław Czerniecki, first published in 1682. I wrote then that it was the oldest cookbook ever printed in Polish. Well, that's no longer true. Polish and Ukrainian historians have recently confirmed that an even older Polish-language cookery book was published a century and a half before Compendium Ferculorum. Not a single volume of that older book has survived to our times, but now we know for sure it was there. Some clues about its possible existence in the past had been know earlier, but as the surviving fragments could be suspected of being some 19th-century hoaxes, there was no certainty. Until now. So let's follow the fascinating history of this new oldest Polish printed cookbook and how it was rediscovered. And then, let's pick and try out a recipe from it – one for beginners, of course.

Cookery Bookery

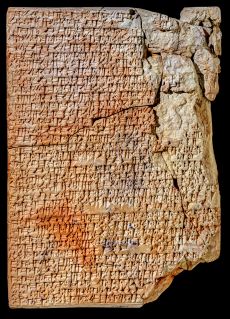

Cookbooks are one of the oldest literary genres in the world. The earliest known culinary recipës were written down in cuneiform script on clay tablets, in Babylonia, around the 19th century BCE.[1] And even these were most likely copied from even older tablets, now lost to time. Because the thing with recipës is that they're much more likely to be copied than written from scratch. You can even see it in the Polish word for "recipë", "przepis", which literally means "something that is rewritten". Oftentimes, the copyist would add something to the recipë, or perhaps makes some abridgements, redactions or modifications – thus allowing the recipë to evolve. In pre-Internet times, culinary recipës were probably some of the best examples of memes, or units of cultural evolution.[2]

For this reason, when it comes to old cookbooks, it's difficult to even speak of authorship in any meaningful way. Even if you can see somebody's name on the title page, you can't be really sure whether it's the name of the original author or perhaps of a translator, editor, copyist or publisher. Or maybe of someone who was a little bit of all the above. For the sake of simplicity, I will refer to such a person as "the author", but keep in mind the they need not necessarily be the actual content creator as understood by modern copyright laws. Besides, even the idea of copyright didn't exist before the 19th century. Before that, people would just go and rewrite or reprint books (culinary or any other) without asking anyone for permission. They would sometimes indicate the original author's name in the copy, but sometimes not. The very idea of authenticity didn't exist either, so a copy wasn't seen as something inferior, but rather as a new, maybe even better version of the original thing. According to Galen of Pergamon (of whom I wrote before), the famous Library of Alexandria was so big thanks to a policy of sending royal customs officers to each ship which called at the local port, in order to gather any scroll of papyrus or parchment they could find and take it for scribes to make copies of. Then, they would give the shining new copies to the ship's captain, while the library would contend itself with the timeworn originals.[3] And this was considered progress, not intellectual property theft!

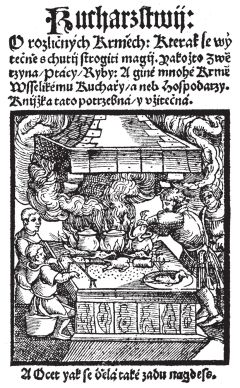

Naturally, copying books by hand was labour-intensive and, therefore, costly (even despite relatively low labour costs in the past). Besides, few people could read anyway, so cookbooks (just like any books for that matter) were a rare luxury. This began to change once Johannes Gutenberg invented the movable-type printing press. He used his invention to publish the first printed book (a Bible, obviously) in 1455. It was only 15 years later in Rome that the first ever cookbook was published in print. It was De honesta voluptate et valetudine (Of Honest Pleasure and Good Health) by Bartolomeo Sacchi (1421–1481), better known as Platina, who served as a papal secretary and librarian, although he actually copied most of the recipës from Martin do Como's handwritten Libro de arte coquinaria (Book of Culinary Arts). It took another 15 years for the first cookbook printed in a vernacular language to come out, namely the German Küchenmeisterei published by Peter Wagner. The 15th century also saw the first printed cookbooks in French, Italian and English, and the first half of the 16th century, in Dutch, Catalan, Spanish and Czech. The latter book, entitled Kuchařstvi and published by Pavel Severýn in 1535, in Prague, was a translation of the aforementioned German text. Both titles can be translated as Cooking Mastery.

And how long did one have to wait for the first cookbook printed in Polish?

A Groundbreaking Discovery

The way historians often make their most interesting discoveries is by dismantling the covers of old books. This is because bookbinders frequently strengthened the covers by gluing together pages torn from even older tomes. Luckily for us, the very first cookbook printed in Polish was among the many books to have fallen victim to this kind of recycling.

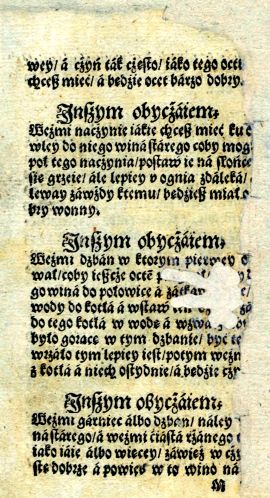

In 1891, Zygmunt Wolski (1862–1931), an apprentice librarian at the Krasiński Library in Warsaw, visited Cezary Wilanowski's (1846–1893) second-hand bookshop, where he found a folder containing four loose sheets of paper that had been removed from an old book cover. The cover bore no title, but it did bear the year of publication: 1538. The four sheets which were reused to strengthen the cover came from three different printed books. Two of the sheets were covered with culinary recipes -- all for different kinds of vinegar, as it happened. Wolski carefully examined the watermarks on the paper, the typeface and the language used in the recipes, and concluded that they must have been printed in the first half of the 16th century.[4]

Wolski found the sheets only a year after Artur Benis (1865–1932), a historian at the Jagiellonian University in Cracow who was busy researching the history of book printing in Poland, had published his work on inventories of Cracow's mid-16th-century print shops. Such inventories were typically made for the purposes of inheritance proceedings and contained lists of books which a print shop owner had printed, but died before he could sell them. And so, in an inventory made in 1555, after the death of Helena Unglerowa, the widow of Florian Ungler (d. 1536), who had been the first person to print books entirely in Polish, there was a mention of 100 unbound copies of a book whose rather unpronounceable title (to anyone who isn't Polish) was Kuchmistrzosthwo (Cooking Mastery).[5] Wolski connected the dots and concluded that the two sheets with torn edges and printed with vinegar recipes may have come from an otherwise lost coobook with such a previously unkown title.

But that's not all. The same year 1891 saw the publication of two further works which shed more light on these two sheets. Firstly, Benis published the second volume of his Inventories, which contained a mention of a single copy of a cookbook owned by Helena Gałczyna (d. 1549), the widow of another Cracow printer, Maciej Szarffenberg (d. 1547). Additionally, four copies of the same book were listed in the inventory of a Szymon Tyrlikowski's book collection. The title indicated in both inventories, however, was written as Kucharstvo or Kucharsthvo (Cookery).[6]

Secondly, Čeněk Zíbrt (1864–1932), a historian at Charles University in Prague, published a reprint of the earliest cookbook printed in the Czech language, that is, the aforementioned Kuchařství.[7] This allowed Władysław Wisłocki (1841–1900), custodian of the Jagiellonian University Library, to compare the vinegar recipes discovered by Wolski with recipes found in the Czech book. And he realized that what Wolski found were indeed fragments of the oldest printed Polish cookbook, which happened to be a translation of the Czech Kuchařství. And, according to Wisłocki, the title was rendered into Polish as Kucharstwo, rather than Kuchmistrzostwo as Wolski had claimed.[8] The question of the book's title has never been fully resolved either way, but somehow, contrary to Wisłocki's view, it is now more commonly referred to as Kuchmistrzostwo.

All this is well and good, but what kind of discovery is it when all that we have from the oldest Polish cookbook are recipes for vinegar? Yes, vinegar was formerly an extremely important preservative and a popular condiment, produced in may different ways, from wine or beer, and sometimes flavoured with various additives. You could, for example, make it like this:

| Take the vessel you wish to use for your vinegar, pour enough old wine to fill half of the vessel, place it in the sunshine and let it stay warm, but better keep it a distance away from fire; this way you will always have good wine vinegar. | ||||||||||

— [Kuchmistrzostwo], [Kraków]: [Hieronim Wietor], [ok. 1540], f1r, Warsaw Public Library, XVI.O.140, own translation

Polish text:

Czech text:

|

Yet still, one would wish for something more than just that.

Another Groundbreaking Discovery

For something more, one had to wait almost forty years, but I believe it was worth it. It was then that Kazimierz Piekarski (1893–1944), head of the Old Prints Department at the Jagiellonian Library, discovered a badly damaged sheet of paper printed with more recipes from Kuchmistrzostwo (or Kucharstwo, if you wish). He removed the sheet, naturally, from the cover of a different tome, namely the 1549 edition of the Latin-language De Tuenda Valetudine Libri Sex (Six Books on the Preservation of Health) by the aforementioned Galen.

Piekarski examined the typefaces used both on the sheet he had found and on the pages with vinegar recipes discovered by Wolski, and then compared them with the typefaces known to be used by different Cracow printers in the first half of the 16th century. And he came to the conclusion that the two fragments came from two different editions of the same cookbook. The sheet found at the Jagiellonian Library was printed with types used at Maciej Szarffenberg's print shop, while the two sheets discovered in Warsaw must have been printed with types employed by Hieronim Wietor (ca. 1480–1547) – rather than by Florian Ungler as Wolski had assumed. But if a hundred unsold copies were found in Mrs. Unlger's inventory, then Ungler must have also printed his own edition of the same cookbook, although not a single copy of that edition has survived to our times.[9] And this would mean that the first cookbook printed in Polish had at least three different editions from three different printers.

But, perhaps more importantly, on this newly discovered sheet, we finally had recipes not for vinegar, but for decent meat dishes. Even game meat, to boot! In the title of the first recipe we can also see a small, but interesting modification made by the 16th-century Polish translator. The original Czech version speaks of "buffalo, bison or other unsual game, not found in our lands", whereas the Polish translation has "buffalo, bison or other game, unusual in Polish lands". On the one hand, I understand the translator's urge to localize the text a little, but on the other, it seems to me that he did it somewhat half-heartedly. It's true that, by the 16th century, bison had already been extinct in Bohemia, or what is now the Czech Republic, but it still roamed the vasts forests of Poland, so it wasn't that exotic to Polish cuisine.

| Buffalo, bison or other game, unusual in Polish lands, but only in foreign countries. Make sauce for it in the following way. Take raisin, figs and make a toast of white bread, put it all in a mortar and let grind, and once it's well ground, pour in some heated wine and strain it through cloth, and having cut up the meat into morsels, cover them with the sauce in a cauldron or a pot, season with pepper, ginger, saffron, cloves and sweeten a little with sugar or honey, and add some fried apples, raisins large and small, almonds and anything else, according to [what you have in] your household. | ||||||||||

— [Kuchmistrzostwo], [Kraków]: [Maciej Szarffenberg], [ok. 1540], f1v, Jagiellonian Library, Old Prints Department, Cim 0.913, own translation

Polish text:

Czech text:

|

And then, there remains the question of how to date this oldest Polish cookbook. Its first edition couldn't be published earlier than 1535, which was when Kuchařství came out in Prague. After all, the translation can't be older that the original. The latest possible date, on the other hand, is 1547, wich is when the cookbook was noted in Szarffenberg's inventory. It was only in the 21st century that it was possible to significantly narrow this 12-year gap, thanks to a catalogue of the library which belonged to Austrian book collector Hieronymus Beck von Leopoldsdorf (1525–1596). One of the items listed in his catalogue is "„Kuchmistrzstwo [sic] Prossowol 1536”. It's unclear what "Prossowol" could mean; it may have refered to some printer who hailed from the village of Proszowice near Cracow. In any case, if that printer published an edition of Kuchmistrzostwo as early 1536, then it would mean that the Polish translation came out only a year after the Czech original.[10]

An Even More Groundbreaking Discovery

Some historians had their doubts, though. If the cookbook was so popular that it had three or even four editions within fifteen years, then how come not a single more or less complete copy has survived to our times? Why is it that the only proofs for the book's existence in the past are just three frayed sheets and a few mentions in inventories, which don't even agree about its title? Even worse, the two sheets with vinegar recipes got somehow misplaced, so for a time, all historians had at their disposal was a facsimilë which Wolski had made and whose authenticity could be questioned.

You could explain these doubt away by saying that the more popular a book is, the more likely it is to be worn down to nothing. It's even more true for a cookery book, which was particularly vulnerable due to its utilitarian character. As for the question of its exact title, one can imagine a scenario in which different printers published the same book under different titles, which wasn't that rare a case at all. Be it as it may, some question marks remained.

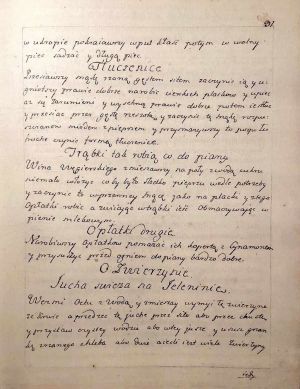

The discovery which practically removed all the remaining doubts about the actual existence of Kuchmistrzostwo and its contents was made about ten years ago by Dr Svitlana Bulatova at the Manuscript Institute of the National Library of Ukraine in Kyiv.[11] But hold on, you may say, why the Manuscript Institute? We're talking about a printed book, aren't we? Well yes, but keep in mind what we said about culinary recipes being contantly copied and rewritten. Back when nobody kept a smartphone equipped with a camera and an OCR function in the pocket -- back when even photocopiers didn't exist -- people commonly copied recipes they found in printed sources by hand. Sometimes they would even create entire manuscript cookbooks that were compilations of recipes taken from diverse sources, both printed and handwritten. It was one such manuscript, entitles Zbiór dla kuchmistrza, tak potraw jako ciast robienia (A Collection for a Master Chef, of Recipes for Both Dishes and Cakes) cookbook that caught Dr. Bulatova's attention and led her to get in touch with the foremost specialist on the history of Polish cuisine, Prof. Jarosław Dumanowski at Copernicus University in Toruń.

The manuscript contains a total of a about a thousand recipes, as well as medical, veterinary and gardening tips -- all written by the same hand. The sources these recipes and tips were gleaned from are not always indicated in the text, but you can see from the different styles and grammars that they must have originated in various historical periods -- mostly within the 16th and 17th centuries. And yet, the copyist who made the manuscript clearly indicated on the title page that he finished his work on 25 July 1757 (such dating is further borne out by water marks found on the paper). Which means by the time the manuscript was created, the recipes which were copied into had already been quite old. The copyist himself didn't sign his work, but the book's first owne left her signatures on three different pages. It was Rozalia Pociejowa née Zahorowska (ca. 1690–1762), a prominent noblewoman living from Volynia in what is now western Ukraine. What led her to commission such a compilation of recipes from previous centuries? Did she wish to study culinary history? Or maybe these old recipes still seemed relevant to her own times and she saw the collection in purely practical terms? We don't really know.

Wiadomo natomiast, skąd pochodzi blok 224 przepisów, które wyróżniają się w rękopisie najbardziej archaicznym językiem. Otóż są to receptury znane z czeskiego Kuchařství, tylko przetłumaczone na język polski. I widać po stylu i gramatyce, że jest to polszczyzna XVI-wieczna, a więc przekładu nie dokonano w momencie tworzenia rękopisu, tylko wykorzystano – albo zachowany jeszcze wtedy w całości, albo już wcześniej przepisany przez kogoś ręcznie – przekład sprzed ponad dwustu lat.

Są też inne poszlaki, które dodatkowo potwierdzają, że autor rękopisu musiał mieć dostęp do tej samej drukowanej książki, z której tylko trzy kartki zachowały się do dziś. Po pierwsze, w rękopisie znajduje się modyfikacja tytułu jednego z przepisów, którą znamy już z karty znalezionej w Jagiellonce: „Zwierzyna bawołowa albo żubrowa i insze nie będące w obyczaju polskiej ziemie, jeno w cudzy[ch] krajach”. A po drugie, w innym przepisie, gdzie jest mowa o rozwałkowaniu żytniego ciasta, znalazła się pewna charakterystyczna literówka: „weźmi ciasta rżanego jako bochen chleba abo więcej i rozdziałaj jako szyroto jest”. Oczywiście powinno być: „szyroko”, czyli: „szeroko”; skąd zatem tam się wzięło to „t”? Ano pewnie stąd, że XVIII-wieczny kopista miał problem z odczytaniem XVI-wiecznego kroju czcionki drukarskiej. A że nie jest łatwo, to zobaczcie sami: kto zgadnie, jakie słowo (wycięte z jednej z zachowanych kart) znajduje się na obrazku poniżej?[12] W każdym razie, jeśli przepisywacz popełnił błąd z powodu złego odczytania drukowanej litery, to znaczy, że musiał przepisywać tekst drukowany – a to z kolei znaczy, iż ten tekst drukowany musiał istnieć!

A zatem: nie zachował się ani jeden kompletny egzemplarz najstarszej książki kucharskiej wydrukowanej w języku polskim, ale wiemy, że ta książka istniała dzięki dawnym inwentarzom drukarni, trzem zachowanym kartkom oraz jednemu kompletnemu rękopisowi, w którym owa książka drukowana została w całości przepisana. Wiemy też, że wydano ją ok. 1536 roku w Krakowie, że nosiła tytuł: Kuchmistrzostwo bądź Kucharstwo oraz że był to przekład wydanej rok wcześniej czeskiej książki pt.: Kuchařství, która z kolei była tłumaczeniem książki niemieckiej pt.: Küchenmeisterei.

A to znaczy, że najstarszą znaną drukowaną książką kucharską w języku polskim nie jest już Compendium ferculorum. Nadal jednak można powiedzieć, iż jest to najstarsza taka książka, która zachowała się do dzisiaj w całości. A zarazem pierwsza wydana drukiem książka kucharska, która nie jest tłumaczeniem, ale została napisana oryginalnie po polsku.

Ugotujmy coś!

No dobrze, to jakie ciekawe przepisy możemy znaleźć w owym Kuchmistrzostwie? Przepisy podzielone są na trzy, a właściwie na cztery rozdziały, z tym że czwarty rozdział nie jest jakoś wyraźnie oddzielony od trzeciego.

W pierwszym, pod nagłówkiem: „O zwierzynie”, wypisano przepisy na dania mięsne. Jest tu sporo przepisów na kurę i inne ptaki (np. „ptacy, którzy bywają w cebuli przyprawiani, a w cieście tak mają być działani”), ale są też receptury mówiące, jak przyrządzić wołowinę („pieczenia wołowa po węgiersku”), wieprzowinę, zająca („zając w cebuli albo bez cebuli”) oraz różnego rodzaju dziczyznę, jak: kuropatwy, sarninę, jeleninę, „wieprzowinę dziką”, wspominaną już „zwierzynę bawołową albo żubrową”, a nawet… wiewiórki. Te ostatnie gotuje się tak:

| Skin them and wash them clean inside, and cook them in meat broth, not too salty, and once they are cooked, make yellow or black sauce for them. To make the yellow sauce: roast squirrel livers and make two or three rye-bread toast, grind them all up in a mortar, dissolve in meat broth and strain. Place the squirrels in the sauce and season with pepper, ginger, mace, and fry some apples as you would for other game, serve in a bowl and remember to salt.

And to make the black sauce: take prunes or fried sweet cherries, make toasts of white bread, place them all in a mixture of vinegar and water, and bring to boil, then strain clean through cloth, add squirrels, bring to boil, season with pepper, ginger, cloves and sprinkle some saffron on top. | ||||||||||

— Zbiór dla kuchmistrza tak potraw jako i ciast robienia wypisany roku 1757 dnia 24 lipca, red. Jarosław Dumanowski, Switłana Bułatowa, Warszawa: Muzeum Pałacu Króla Jana III w Wilanowie, 2021, p. 141, own translation

Original text:

Czech text:

|

Oba przepisy na wiewiórkę – w ich czeskiej wersji – odtworzyli kilka lat temu Czesi: popularyzator gastronomii Roman Vaněk i szef kuchni Pavel Mencl, z pomocą historyka Martina Franca, w programie telewizyjnym z serii Zmlsané dějiny (Łakoma historia). Pewną trudność nastręczyło im zdobycie podstawowego surowca, gdyż rodzime, rude wiewiórki są w Europie pod ochroną; zamiast nich trzeba było sprowadzić z Anglii wiewiórki szare, które masowo odławia się tam jako gatunek inwazyjny. Efekt końcowy był dla rekonstruktorów całkiem zadowalający, tylko kolory sosów wyszły nieco inne, niż można było się spodziewać: zamiast żółtego i czarnego – różne odcienie brązu. Widać, że barwy potraw były postrzegane nieco inaczej w czasach, gdy nie dodawano do żywności sztucznych barwników.

No ale miało być dla początkujących, więc szukamy dalej.

Następny rozdział jest „o rybach”, czyli o żywności typowo postnej. Jest tu wiele przepisów na karpia, szczupaka, sztokfisz (czyli suszonego dorsza), a także na łososia, węgorza, piskorze, minogi oraz raki. Sporo miejsca zajmują tu przepisy na różne galarety, a szczególnie wykwintny jest tu pierwszy przepis, na „kisielicę z karpiów czterech barw”, czyli na karpia w kwaśnej galarecie z żuru, w czterech kolorach: czarnym (barwionym krwią), brunatnym (cynamonem), zielonym (natką pietruszki) oraz białym (śmietaną). To też raczej dla kucharzy bardziej zaawansowanych.

Przepis na zwierzynę bawołową albo żubrową (tylko że z wołowiną zamiast grubej dziczyzny), a także na różne rodzaje kisielic, odtworzył Maciej Nowicki, szef kuchni Muzeum Pałacu Króla Jana III w Wilanowie, z pomocą prof. Dumanowskiego, w czwartym odcinku serialu Historia kuchni polskiej, który poświęcony jest właśnie Kuchmistrzostwu.

Trzeci rozdział to „karmie sobotniej wypisanie”. Ów sobotni pokarm to potrawy przewidziane na post sobotni, a więc łagodniejszy od piątkowego i dopuszczający spożywanie nabiału. W tym rozdziale dominują przepisy na rozmaite kluski i kasze oraz farmuszki, czyli zupy zagęszczane żółtkami. Na końcu, w niewydzielonym wyraźnie czwartym rozdziale, są jeszcze – częściowo już nam znane – przepisy na ocet. Zostańmy jednak przy kaszach. Słowo „kasza” miała dawniej nieco szersze znaczenie niż dzisiaj i obejmowało wszystkie potrawy o konsystencji kaszy. Można było na przykład podsmażyć jabłka, przetrzeć je przez sito i to była kasza z jabłek.

Moją uwagę zwrócił jednak przepis na „kaszę z ryżu”, czyli nic innego niż ryż ze śmietaną, cukrem i cynamonem.

| Kaszę z ryżu tak działaj: Weźmij ryżu, coć się widzi, a czystej śmietany, uwarz ją pierwej, a potym ten ryż wypłucz, a kładź do tej śmietany, a omaścisz masłem i mieszaj, aby się nie zewrzało, tedy będzie czysta [tj. nieprzypalona] kasza, a potem, gdy dasz na misę, posyp cynamonem i cukrem. | ||||||

— Zbiór dla kuchmistrza tak potraw jako i ciast robienia wypisany roku 1757 dnia 24 lipca, red. Jarosław Dumanowski, Switłana Bułatowa, Warszawa: Muzeum Pałacu Króla Jana III w Wilanowie, 2021, p. 168

Original text:

|

Myślę, że prawie każdy Polak przynajmniej raz w życiu jadł coś podobnego. Główna różnica w samej recepturze jest taka, że dziś ugotowalibyśmy ryż na mleku, a dopiero potem polali śmietaną, natomiast tutaj ryż gotuje się już w śmietanie. Istotniejsza różnica jest w tym, jak ten przysmak był i jest postrzegany. Dla nas jest to proste danie, wręcz banalne, choć możemy myśleć o nim z nostalgią jako o słodkim smaku dzieciństwa. W XVI w. był to szczyt luksusu. Ryż, cukier i cynamon trzeba było sprowadzać z zamorskich krain za grube pieniądze. Masło i śmietanę pozyskiwano wprawdzie lokalnie, lecz były to najdroższe produkty mleczarskie. W kuchni, w której szczególną rolę odgrywały kolory, potrawy białe ceniono szczególnie wysoko – stąd dbałość, by ryżu przypadkiem nie przypalić. Krótko mówiąc – była to kasza na bogato.

Do wykonania tego przepisu użyłem śmietany 30%, którą jednak rozrzedziłem nieco mlekiem. Cukru – trzcinowego, bo buraczanego w XVI w. nie znano – dodałem już na etapie gotowania, żeby dobrze się rozpuścił. Na koniec posypałem ryż sproszkowanym cynamonem – i gotowe! Smakowało przyjemnie – jak ryż ze śmietaną, cukrem i cynamonem.

A gdyby ktoś chciał sobie wybrać jakieś inne przepisy z najstarszej polskiej książki kucharskiej, to mam dobrą wiadomość: cały Zbiór dla kuchmistrza został w 2011 r. naukowo zredagowany przez państwa Bułatową i Dumanowskiego, i wydany przez Muzeum Pałacu Króla Jana III w Wilanowie. W ten sposób po prawie półtysiącleciu od pierwszego wydania receptury z Kuchmistrzostwa ponownie ukazały się drukiem.

Timeline of Early Printed Cookbooks

Na koniec, w charakterze podsumowania: mała tabelka, mająca pokazać, kiedy i w jakiej kolejności ukazywały się pierwsze drukowane książki kucharskie w poszczególnych językach europejskich do połowy XVI w. – na tle wybranych wydarzeń z historii ogólnej.

| First cookbooks printed in given languages | Decade | Selected events in Europe, for guidance |

|---|---|---|

| 1451–1460 |

• 1453, Contantinople (Istanbul) – Ottoman Turks under Sultan Mehmed II capture the capital city of the eastern Roman Empire | |

|

• Bartolomeo Platina (☛), De honesta voluptate et valetudine, Rome ca. 1470 – in Latin. |

1461–1470 |

• 1461, France – François Villon writes his testament in verse. |

| 1471–1480 |

• 1473, North Sea – as part of the Anglo-Hanseatic War, corsairs from Danzig (Gdańsk) loot the Last Judgement triptych (☚) by Hans Memling (now still in Gdańsk). | |

|

• Peter Wagner, Küchenmeisterei, Nuremberg 1485 – in German. |

1481–1490 |

• 1489, Cracow – Veit Stoß finishes his work on St. Mary's altarpiece, a masterpiece of Gothic sculpture (still in Cracow). |

|

• Richard Pynson, The Boke of Cokery, London 1500 – in English. |

1491–1500 |

• 1492 – Cristoffa Colombo (☚) sails under a Spanish ensign in search of a western route to India, ending up in the Caribbean. |

| 1501–1510 |

• 1505, Radom – King Alexander Jagiellon of Poland (☚) signs the Nihil Novi act, establishing parliamentary monarchy in his kingdom. | |

|

• Thomas van der Noot, Een notabel boecxken van cokeryen, Brussels 1514 – in Dutch. |

1511–1520 |

• 1517, Wittenberg – Martin Luther publishes his 95 theses against the sale of indulgencies, kicking off the Protestant Reformation. |

|

• Robert de Nola, Libro de guisados, Toledo 1525 – in Spanish (translated from Catalan). |

1521–1530 |

• 1522, Graudenz (Grudziądz) – Niklas Koppernigk aka Copernicus (☚), canon of Ermland, delivers a speech about monetary policy at the dietine (regional assembly) of Royal Prussia. |

|

• Pavel Severýn, Kuchařství, Prague 1535 – in Czech (translated from German). |

1531–1540 |

• 1534, London – King Henry VIII (☚) becomes the head of the Church of England. |

References

- ↑ Gojko Barjamovic et al.: The Ancient Mesopotamian Tablet as Cookbook, in: Lapham's Quarterly, 11 June 2019

- ↑ Many people think of memes as nothing but silly pictures shared on the Internet, but they are, in fact, as old as human culture itself. The Internet is only a new medium for memes to spread in, faster than ever before. The notion of memes, as cultural equivalents of genes, was coined by the famous biologist Prof. Richard Dawkins in 1976 (when the Interent was still in its infancy), who wanted to show that you can also study evolution outside of biology (R. Dawkins: Memes: the new replicators, in: The Selfish Gene, Oxford University Press, 1989, p. 189–201). The very idea of a meme would soon become a successful and quickly evolving meme in and of itself.

- ↑ Galen of Pergamon: Commentary on Hippocrates' Epidemics, in: Andrew Smith: Attalus

- ↑ Zygmunt Wolski: Kuchmistrzostwo: Szczątki druku polskiego z początku w. XVI, Biała Radziwiłłowska: self-published, 1891, p. 11–12

- ↑ Artur Benis: Materyały do historyi drukarstwa i księgarstwa w Polsce, vol. I. Inwentarze księgarń krakowskich Macieja Scharffenberga i Floryana Unglera (1547, 1551), Kraków: Akademia Umiejętności, 1890

- ↑ Artur Benis: Materyały do historyi drukarstwa i księgarstwa w Polsce, vol. II. Inwentarze bibliotek prywatnych (1546–1553), Kraków: Akademia Umiejętności, 1891

- ↑ Kuchařství: O rozličných krmích, kterak se s chutí strojiti mají, red. Čeněk Zíbrt, Praha: F. Šimáček, 1891

- ↑ Władysław Wisłocki: Przewodnik Bibliograficzny, 14/10, Kraków: self-published, October 1891, p. 166–167

- ↑ Kazimierz Piekarski: Miscellanea Bibljograficzne: „Kuchmistrzostwo” Macieja Szarffenberga, in: Przegląd Bibljoteczny, IV, Kraków: Wydawnictwo Związku Bibljotekarzy Polskich, 1930, p. 415–418

- ↑ Magdalena Herman: Ślady pierwszej polskiej książki kucharskiej, in: Silva Rerum, Warszawa: Muzeum Pałacu Króla Jana III w Wilanowie, 3 December 2020

- ↑ Світланa Олегівнa Булатова: Рукописна книга ХVIII ст. з історії старопольської кухні „Zbiór dla kuchmistrza tak potraw jako ciast robienia” з фондів Інституту рукопису Національної бібліотеки України імені ВІ Вернадського, in: Рукописна та книжкова спадщина України, 20, 2016, p. 22–42

- ↑ Poprawna odpowiedź: „kotła”.

Bibliografia

- [Kuchmistrzostwo], Kraków: ok. 1540

- zachowany fragment (przepisy na ocet), Biblioteka Publiczna m.st. Warszawy – Biblioteka Główna Województwa Mazowieckiego, sygn. XVI.O.140

- zachowany fragment (przepisy na dania mięsne), Biblioteka Jagiellońska, Dział Starodruków, sygn. Cim 0.913

- Artur Benis: Materyały do historyi drukarstwa i księgarstwa w Polsce, Kraków: Akademia Umiejętności

- Aleksander Brückner: Źródła do dziejów literatury i oświaty polskiej: VII. O pismach dziś nieznanych: IV. Rozmaitości, in: Biblioteka Warszawska, t. I, Warszawa: 1895, p. 24–28

- Switłana Bułatowa, Jarosław Dumanowski: „Kuchmistrzostwo”: Kopia tekstu najstarszej polskiej książki kucharskiej z XVI wieku, in: Silva Rerum, Warszawa: Muzeum Pałacu Króla Jana III w Wilanowie, 18 lipca 2022

- Jarosław Dumanowski: Tajemnica pierwszej polskiej książki kucharskiej, in: Silva Rerum, Warszawa: Muzeum Pałacu Króla Jana III w Wilanowie, 7 lutego 2009

- Karol Estreicher: Bibliografia polska, cz. III, vol. XIX, Kraków: Akademia Umiejętności, 1905, p. 355

- Magdalena Herman: Ślady pierwszej polskiej książki kucharskiej, in: Silva Rerum, Warszawa: Muzeum Pałacu Króla Jana III w Wilanowie, 3 grudnia 2020

- Henry Notaker: A History of Cookbooks: From Kitchen to Page over Seven Centuries, Oakland: University of California Press, 2017

- Kazimierz Piekarski: Miscellanea Bibliograficzne: „Kuchmistrzostwo" Macieja Szarffenberga, in: Przegląd Biblioteczny, IV, Kraków: Wydawnictwo Związku Bibljotekarzy Polskich, 1930, p. 415–418

- Marta Sikorska: Smak i tożsamość: Polska i niemiecka literatura kulinarna w XVII wieku, Warszawa: Muzeum Pałacu Króla Jana III w Wilanowie, 2019

- Magdalena Spychaj: „Spis o krmích” z XV wieku: u źródeł czeskiej literatury kulinarnej, in: Przegląd Historyczny, 102/4, 2011, p. 591–607

- Władysław Wisłocki: Przewodnik Bibliograficzny, 14/10, Kraków: nakładem własnym, październik 1891, p. 166–167

- Zygmunt Wolski: Kuchmistrzostwo: Szczątki druku polskiego z początku w. XVI, Biała Radziwiłłowska: nakładem autora, 1891

- Zbiór dla kuchmistrza tak potraw jako ciast robienia wypisany roku 1757 dnia 24 lipca, red. Jarosław Dumanowski, Switłana Bułatowa, Warszawa: Muzeum Pałacu Króla Jana III w Wilanowie, 2021

- Jarosław Dumanowski, Switłana Bułatowa: Książka kucharska Rozalii Pociejowej i Ludwiki Honoraty Lubomirskiej, in: Zbiór dla kuchmistrza…, p. 11–112

- Čeněk Zíbrt: Staročeské umění kuchařské, Praha: Stará garda mistrů kuchařů, 1927

| ◀️ Previous | 📜 List of posts | Next ▶️ |

| ⏮️ First | 🎲 Random post | Latest ⏭️ |

- Artur Benis

- Switłana Bułatowa

- Martin do Como

- Stanisław Czerniecki

- Jarosław Dumanowski

- Galen z Pergamonu

- Kazimierz Piekarski

- Bartolomeo Platina

- Władysław Wisłocki

- Zygmunt Wolski

- Čeněk Zíbrt

- Kyiv

- Cracow

- Prague

- Warsaw

- Sugar

- Cinnamon

- Carp in aspic

- Rice

- Cream

- Squirrel

- Antiquity

- Middle Ages

- Early Modern Period

- 19th century

- 20th century

- 21st century

- Recipes