Difference between revisions of "Old Polish Cookery for Beginners"

| Line 4: | Line 4: | ||

== A Collection of Dishes == | == A Collection of Dishes == | ||

| − | The book in question, first published in 1682, was written by Stanisław Czerniecki (pronounced ''stah-{{small|NEE}}-swahf churn-{{small|YET}}-skee''), a steward and chef at the court of the Princes Lubomirski. He gave it a bilingual | + | The book in question, first published in 1682, was written by Stanisław Czerniecki (pronounced ''stah-{{small|NEE}}-swahf churn-{{small|YET}}-skee''), a steward and chef at the court of the Princes Lubomirski. He gave it a bilingual (Latin-Polish) title, ''Compendium ferculorum, albo Zebranie potraw'' (''A Collection of Dishes''), but the contents were entirely in Polish (contrary to what Ms. Mary Ellen Snodgrass suggested in her ''Encyclopedia of Kitchen History'', where she described ''Compendium ferculorum'' as Poland's "Latin standard"<ref>{{Cyt |

| nazwisko = Snodgrass | | nazwisko = Snodgrass | ||

| imię = Mary Ellen | | imię = Mary Ellen | ||

| Line 13: | Line 13: | ||

| rok = 2004 | | rok = 2004 | ||

| strony = 270 | | strony = 270 | ||

| − | }}</ref>) Czerniecki was well aware that his was the first cookbook ever published in his native tongue. "As no one before me has yet wished to present to the world such useful knowledge in our Polish language," he wrote in his opening line, "I have dared, {{...}} despite my ineptitude, to offer my {{...}} collection of dishes to the Polish world."<ref>{{Cyt | + | }}</ref>). Czerniecki was well aware that his was the first cookbook ever published in his native tongue. "As no one before me has yet wished to present to the world such useful knowledge in our Polish language," he wrote in his opening line, "I have dared, {{...}} despite my ineptitude, to offer my {{...}} collection of dishes to the Polish world."<ref>{{Cyt |

| nazwisko = Czerniecki | | nazwisko = Czerniecki | ||

| imię = Stanisław | | imię = Stanisław | ||

| Line 23: | Line 23: | ||

}}, Dedication, own translation</ref> The author divided his work into three chapters of about one hundred recipes each, for meat dishes, fish dishes and other dishes, respectively. | }}, Dedication, own translation</ref> The author divided his work into three chapters of about one hundred recipes each, for meat dishes, fish dishes and other dishes, respectively. | ||

| − | The recipes, though, are not easy to | + | The recipes, though, are not easy to follow. First, they're in Polish, which may be an inconvenience, if you don't speak the language. But even you did, you'd still have to wade through 17th-century Polish spelling, interpunction and typeface. Let's take the example below. You could probably make out the name of the dish, printed in roman type, but what about the actual recipe, written in blackletter? |

[[File:Compendium 15.jpg|600px|Potráwá żołta w dobrey iuſze, álbo po Krolewſku. Weźmiy Járząbká álbo Kuropátwę/ Ptáßki álbo Gołembie/ Kápłoná álbo Cielęćinę/ álbo co chceß/ wymocz/ ſpuść w gárniec/ zaſol/ odwarż/ odbierz/ nácedz znowu tym roſołem/ y pietrußki włoż/ á gdy dowiera/ wley Gąßczu/ Octu/ ſłodkośći/ Száfranu/ Pieprzu/ Cynámonu/ Rozenkow oboygá/ Limoniy/ przywarz á dáy ná miſę.]] | [[File:Compendium 15.jpg|600px|Potráwá żołta w dobrey iuſze, álbo po Krolewſku. Weźmiy Járząbká álbo Kuropátwę/ Ptáßki álbo Gołembie/ Kápłoná álbo Cielęćinę/ álbo co chceß/ wymocz/ ſpuść w gárniec/ zaſol/ odwarż/ odbierz/ nácedz znowu tym roſołem/ y pietrußki włoż/ á gdy dowiera/ wley Gąßczu/ Octu/ ſłodkośći/ Száfranu/ Pieprzu/ Cynámonu/ Rozenkow oboygá/ Limoniy/ przywarz á dáy ná miſę.]] | ||

| Line 32: | Line 32: | ||

{{Cytat | {{Cytat | ||

| '''Yellow Dish in Good Sauce, in the Royal Style'''<br> | | '''Yellow Dish in Good Sauce, in the Royal Style'''<br> | ||

| − | Take a hazel grouse or a partridge, small birds or pigeons, a capon or veal, or whatever [kind of meat] you want; soak in water, put in a pot, salt, bring to boil, debone, cover again with the stock, add parsley; and when boiling, add coulis [thick vegetable sauce], vinegar, sugar, saffron, pepper, cinnamon, both kinds of raisins, limes; bring to boil and serve in a bowl. | + | Take a hazel grouse or a partridge, small birds or pigeons, a capon or veal, or whatever [kind of meat] you want; soak in water, put in a pot, salt, bring to boil, debone, cover again with the stock, add parsley; and when boiling, add coulis [thick vegetable sauce], vinegar, sugar, saffron, pepper, cinnamon, both kinds of raisins, and limes; bring to boil and serve in a bowl. |

| oryg ='''Potrawa żółta w dobrej jusze, albo po królewsku'''<br> | | oryg ='''Potrawa żółta w dobrej jusze, albo po królewsku'''<br> | ||

Weźmij jarząbka albo kuropatwę, ptaszki albo gołębie, kapłona albo cielęcinę, albo co chcesz; wymocz, spuść w garniec, zasól, odwarz, odbierz, nacedź znowu tym rosołem i pietruszki włóż; a gdy dowiera, wlej gąszczu, octu, słodkości, szafranu, pieprzu, cynamonu, rożenków obojga, limonij; przywarz, a daj na misę. | Weźmij jarząbka albo kuropatwę, ptaszki albo gołębie, kapłona albo cielęcinę, albo co chcesz; wymocz, spuść w garniec, zasól, odwarz, odbierz, nacedź znowu tym rosołem i pietruszki włóż; a gdy dowiera, wlej gąszczu, octu, słodkości, szafranu, pieprzu, cynamonu, rożenków obojga, limonij; przywarz, a daj na misę. | ||

| Line 46: | Line 46: | ||

}} }} | }} }} | ||

| − | That better, isn't it? But I bet you'd still have a hard time actually cooking from this recipe. Where's the list of ingredients? Where are the quantities and proportions? What about caloric contents? Cooking time and temperatures? How many people does it serve? We've got used to taking certain elements of a cooking recipe for granted, but it turns out they just hadn't been invented yet in the 17th century. | + | That's better, isn't it? But I bet you'd still have a hard time actually cooking from this recipe. Where's the list of ingredients? Where are the quantities and proportions? What about caloric contents? Cooking time and temperatures? How many people does it serve? We've got used to taking certain elements of a cooking recipe for granted, but it turns out they just hadn't been invented yet in the 17th century. |

[[File:Nowy Wiśnicz z powietrza.jpg|thumb|left|The castle of Nowy Wiśnicz, which was once the family seat of the Princes Lubomirski; this is where Stanisław Czerniecki worked as a steward and chef, and where he wrote down his recipes in the first cookbook printed in Polish.]] | [[File:Nowy Wiśnicz z powietrza.jpg|thumb|left|The castle of Nowy Wiśnicz, which was once the family seat of the Princes Lubomirski; this is where Stanisław Czerniecki worked as a steward and chef, and where he wrote down his recipes in the first cookbook printed in Polish.]] | ||

| − | + | Another thing we take for granted is that it's usually the same person who buys a cookbook, reads it and cooks according to its recipes. In the 17th century, though, it was quite normal for these three roles to be separated. The book would have been purchased by someone who could afford it, that is, a rich nobleman or a magnate (the Polish equivalent of an aristocrat). Or, rather, it would have been his wife, the lady of the house. She wouldn't have bought the book for herself, however, but for the head chef (or "master cook") she'd had employed. It was the head chef's job to manage the entire kitchen staff, order the necessary ingredients from external suppliers and make decisions about what would be served on the lord's table (having agreed the menu and the costs with the lady). So the recipes in the cookbook would have been read by the head chef – an experienced professional who didn't need all the proportions, temperatures and cooking times, because he already kept this knowledge in his head. But here comes another twist: he would have read the recipes aloud – not to himself, but to the kitchen staff, who would actually carry the instructions out. We can tell this by the grammatical forms used in the book; it's always the singular second-person imperative, indicating a direct order that you could issue to your subordinate, but never to a magnate's wife (the owner of the book). Czerniecki, for example, would have never addressed his own employer, Princess Helena Tekla Lubomirska, by the familiar "''ty''" ("thou"), but consistently called her "Your Princely Grace, my Most Charitable Lady and Benefactress". | |

| − | |||

| − | + | Let's go back to the recipe. What do we have here? Stewed meat with sweet, sour and spicy seasoning; taste combinations that most Poles today would consider typical for Indian or Thai cuisines, but never for Old Polish cookery. And yet, this is exactly the kind of cooking that the Polish lords of yore would have priced the most and this is what we will find throughout Czerniecki's cookbook. So does it even make sense to recreate these old recipes, if the final effect may well turn out inedible to our modern palates? | |

== Eggy Recipes == | == Eggy Recipes == | ||

Revision as of 11:50, 6 January 2020

Cooking according to centuries-old recipes can be a real challenge even for experienced chefs. There are, however, dishes so simple that even beginner cooks could hardly fail to get them right – whether hundreds of years ago or today (let alone today, I should say, with modern kitchen tools at our disposal). So here's a handful of easy recipes I've picked for culinary novices from the oldest printed Polish-language cookbook.

A Collection of Dishes

The book in question, first published in 1682, was written by Stanisław Czerniecki (pronounced stah-NEE-swahf churn-YET-skee), a steward and chef at the court of the Princes Lubomirski. He gave it a bilingual (Latin-Polish) title, Compendium ferculorum, albo Zebranie potraw (A Collection of Dishes), but the contents were entirely in Polish (contrary to what Ms. Mary Ellen Snodgrass suggested in her Encyclopedia of Kitchen History, where she described Compendium ferculorum as Poland's "Latin standard"[1]). Czerniecki was well aware that his was the first cookbook ever published in his native tongue. "As no one before me has yet wished to present to the world such useful knowledge in our Polish language," he wrote in his opening line, "I have dared, […] despite my ineptitude, to offer my […] collection of dishes to the Polish world."[2] The author divided his work into three chapters of about one hundred recipes each, for meat dishes, fish dishes and other dishes, respectively.

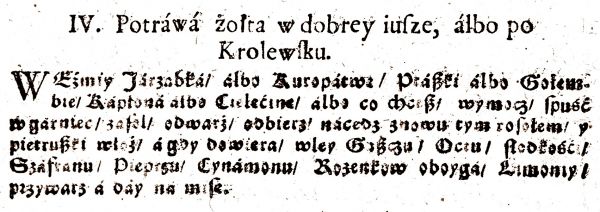

The recipes, though, are not easy to follow. First, they're in Polish, which may be an inconvenience, if you don't speak the language. But even you did, you'd still have to wade through 17th-century Polish spelling, interpunction and typeface. Let's take the example below. You could probably make out the name of the dish, printed in roman type, but what about the actual recipe, written in blackletter?

But don't worry; I've translated it for you:

| Yellow Dish in Good Sauce, in the Royal Style Take a hazel grouse or a partridge, small birds or pigeons, a capon or veal, or whatever [kind of meat] you want; soak in water, put in a pot, salt, bring to boil, debone, cover again with the stock, add parsley; and when boiling, add coulis [thick vegetable sauce], vinegar, sugar, saffron, pepper, cinnamon, both kinds of raisins, and limes; bring to boil and serve in a bowl. | ||||

— Stanisław Czerniecki: Compendium ferculorum albo Zebranie potraw, Kraków: w drukarni Jerzego i Mikołaja Schedlów, 1682, p. 15

Original text:

|

That's better, isn't it? But I bet you'd still have a hard time actually cooking from this recipe. Where's the list of ingredients? Where are the quantities and proportions? What about caloric contents? Cooking time and temperatures? How many people does it serve? We've got used to taking certain elements of a cooking recipe for granted, but it turns out they just hadn't been invented yet in the 17th century.

Another thing we take for granted is that it's usually the same person who buys a cookbook, reads it and cooks according to its recipes. In the 17th century, though, it was quite normal for these three roles to be separated. The book would have been purchased by someone who could afford it, that is, a rich nobleman or a magnate (the Polish equivalent of an aristocrat). Or, rather, it would have been his wife, the lady of the house. She wouldn't have bought the book for herself, however, but for the head chef (or "master cook") she'd had employed. It was the head chef's job to manage the entire kitchen staff, order the necessary ingredients from external suppliers and make decisions about what would be served on the lord's table (having agreed the menu and the costs with the lady). So the recipes in the cookbook would have been read by the head chef – an experienced professional who didn't need all the proportions, temperatures and cooking times, because he already kept this knowledge in his head. But here comes another twist: he would have read the recipes aloud – not to himself, but to the kitchen staff, who would actually carry the instructions out. We can tell this by the grammatical forms used in the book; it's always the singular second-person imperative, indicating a direct order that you could issue to your subordinate, but never to a magnate's wife (the owner of the book). Czerniecki, for example, would have never addressed his own employer, Princess Helena Tekla Lubomirska, by the familiar "ty" ("thou"), but consistently called her "Your Princely Grace, my Most Charitable Lady and Benefactress".

Let's go back to the recipe. What do we have here? Stewed meat with sweet, sour and spicy seasoning; taste combinations that most Poles today would consider typical for Indian or Thai cuisines, but never for Old Polish cookery. And yet, this is exactly the kind of cooking that the Polish lords of yore would have priced the most and this is what we will find throughout Czerniecki's cookbook. So does it even make sense to recreate these old recipes, if the final effect may well turn out inedible to our modern palates?

Eggy Recipes

Nie martwcie się: wśród ponad 300 przepisów zawartych w Compendium ferculorum można znaleźć kilka potraw na tyle prostych, że ich receptury od wieków niemal nie zmieniły się i – nawet zapisane staropolszczyzną – brzmią zaskakująco znajomo. Są to dania jajeczne, zapewne tak stare, jak długo ludzie hodują kury. Zacznijmy od receptury najbanalniejszej, czyli na zwykłą jajecznicę:

| Jajecznica prosta Rozbij jajec, wlej na masło w rynkę, a usmażywszy, daj z rynką na stół; możesz też cebulki młodej, zielonej albo pietruszki drobno ukrajać. |

| — Op. cit., s. 74 |

Oprócz tego, że dziś zamiast rynki, czyli ceramicznego rondelka, użylibyśmy teflonowej patelni, to przepis ani na jotę się nie zmienił. Jest to jajecznica tak prosta, a nawet prostacka, że aż dziw bierze, iż przepis na nią w ogóle znalazł się w książce kucharskiej przeznaczonej dla magnackich kuchmistrzów.

Jeśli jajecznica zdaje się Czytelnikowi daniem zbyt łatwym i chciałby spróbować czegoś wymagającego odrobinę większego obycia kuchennego, to proponuję przepis Czernieckiego na naleśniki, który też prawie w ogóle się nie zestarzał:

| Naleśnik Rozbij jajec z mlekiem i trochą mąki, zynguj masłem rynkę albo kielemkę [czyli: posmaruj masłem rondel], wlewaj po trosze, a piecz cienko, a polawszy masłem, daj na stół. |

| — Op. cit., s. 75 |

I jeszcze jeden przepis jajeczny, tym razem na grzybek, czyli coś w rodzaju omleta (według Kuchni polskiej z 2005 r., grzybek różni się od omleta tym, że do tego pierwszego dodaje się mąki;[3] ale Czerniecki uważał, że, choć do grzybka można dodać mąki, to lepiej nie):

| Grzybek Rozbij jajec z mlekiem, a jeżeli chcesz, możesz przydać mąki trochę, jednak lepiej bez mąki; przydaj rożenków [rodzynków] drobnych, cynamonu, wlej w rynkę na masło gorące, a smaż i przewróć; usmażywszy, pocukruj, a daj na stół. |

| — Op. cit., s. 75 |

Winey Eggs

Któż nie pamięta z czasów studenckich tego przepysznego dania śniadaniowego, którym była jajecznica na winie? Brało się do tego jajka, masło i wszystko, co się nawinie (stąd nazwa). Nazwa dania jest oczywiście żartem, no bo kto by dodawał do jajecznicy prawdziwego wina? Ani to opłacalne, ani smaczne.

A jednak, oprócz wspomnianej wyżej jajecznicy prostej, można u Czernieckiego znaleźć też przepis na jajecznicę z winem. Tym razem to nie żart; faktycznie chodzi o potrawę z jajek i wina. Oto jak się ją przyrządza:

| Jajecznica z winem Masła w rynce rozpuść, jajec rozbij z winem i cukrem, i cynamonem; ubij to społem, a wlej na gorące masło; usmażywszy, daj z rynką, a nie mieszaj. |

| — Op. cit., s. 74 |

Z ostatniego polecenia (nie mieszaj) można wywnioskować, że chodzi tu raczej znowu o omlet niż o jajecznicę w dzisiejszym rozumieniu. I jest to omlet na słodko – z cukrem i cynamonem – więc i wino pewnie powinno być słodkie.

Ten przepis postanowiłem wypróbować sam. Użyłem do tego trzech jajek, łyżeczki cukru, szczypty soli i cynamonu oraz ⅓ kieliszka wina. Jako że dawni Polacy kochali węgrzyna, to uznałem, że najlepszy do tego będzie słodki tokaj.

Jajka roztrzepałem ze szczyptą soli, następnie dodałem cukru, cynamonu, wina i wylałem na rozgrzane na patelni masło. Choć w orginalnym przepisie nie było rodzynków, to jednak je dodałem, uważając, że byłoby to zgodne z duchem epoki.

Masa jajeczno-winna z początku była dość puszysta, ale potem opadła, co, jak sądzę, było spowodowane dodaniem wina, bo w normalnym omlecie nigdy mi się coś takiego nie zdarzyło. Taki omlet za to dał się łatwo złożyć na pół, a nawet na ćwierć.

Podsmażyłem go jeszcze trochę, przełożyłem na talerz (taka zaleta teflonu, że nie trzeba dawać omleta z rynką na stół) i posypałem cukrem pudrem (czy, jakby powiedział Czerniecki, cukrem faryną).

Mnie smakowało, winny aromat tokaja był wyraźnie wyczuwalny i lekko przełamywał słodycz cukru. I co również ważne, byłem tym śniadaniem zupełnie najedzony.

References

- ↑ Mary Ellen Snodgrass: Encyclopedia of Kitchen History, New York, London: Fitzroy Dearborn, 2004, p. 270

- ↑ Stanisław Czerniecki: Compendium ferculorum albo Zebranie potraw, Kraków: w drukarni Jerzego i Mikołaja Schedlów, 1682, Dedication, own translation

- ↑ Zofia Surzycka-Mliczewska (red.): Kuchnia polska, Warszawa: Polskie Wydawnictwo Ekonomiczne, 2005, p. 262–263

Bibliography

Jeśli ktoś chciałby sobie poczytać oryginalne wydanie Compendium ferculorum z 1682 r., to polecam skany w Polonie, czyli witrynie internetowej Biblioteki Narodowej. Na szczęście nie jest to jedyny sposób zapoznania się z tym dziełem, bo można też kupić wydanie współczesne, zredagowane i opatrzone komentarzem przez prof. Jarosława Dumanowskiego, a wydane przez Muzeum Pałacu Jana III w Wilanowie jako pierwsza książka z serii Monumenta Poloniae Culinaria:

- Stanisław Czerniecki: Compendium Ferculorum albo Zebranie Potraw, Jarosław Dumanowski, Magdalena Spychaj (ed.), Stanisław Lubomirski (preface), Warszawa: Muzeum Pałac w Wilanowie, 2010

| ◀️ Previous | 📜 List of posts | Next ▶️ |

| ⏮️ First | 🎲 Random post | Latest ⏭️ |