Difference between revisions of "Good King Stanislas and the Forty Thieves"

| (93 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | {{Cytat | + | {{data|24 April 2019}} |

| − | | | + | [[File:babà da infornare.jpg|thumb|upright|Neapolitan ''babà al rum'' still in their moulds. This photo and the next come from the blog ''[https://profumodilievito.blogspot.com/search?q=baba Profumo di lievito]'' (''The Scent of Yeast'').]] |

| − | + | Easter season is here, which is a good occasion to write something about the ''baba'', a tall, rich yeast cake traditionally served in Poland for Easter breakfast. But before we move on to the Polish ''baba'', let’s take a look at the ''babà al rum'', which the Neapolitans consider their unique regional speciality. | |

| − | | | + | |

| − | | oryg | + | == ''Si ’nu babà'' == |

| − | + | A ''babà al rum'' is a kind of oversized cupcake that is baked, usually more than one at a time, in a can-shaped mould so that the dough rises over the edge to form a mushroom-like shape. Once it’s done, removed from the mould and allowed to cool down, the ''babà'' is soaked in syrup mixed with some rum (hence the ''al rum'' in the name) or ''limoncello'' (local lemon liqueur). Neapolitans prize this delicacy so much that the word ''babà'' has become a synonym for anything or anyone that is particularly sweet and attractive. This is what Ms. Carla Nuti, an Italian psychologist who describes human personalities by comparing them with desserts, has to say about the origin of the ''babà'' and its name: | |

| + | {{clear}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[File:babà crema.jpg|thumb|upright|A Neapolitan ''babà al rum'' with pastry cream]] | ||

| + | {{ Cytat | ||

| + | | “Tu si nu babà!” [literally: you are a baba!] is a compliment Neapolitans use to tell their girlfriends that they are lovely, beautiful, attractive and sweet. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The babà, a truly Neapolitan speciality, is in fact of Polish origin. Stanislao Leszczinski [sic], King of Poland and a great gourmet, is said to have one day angrily pushed away a dessert he wasn’t fond of and to have accidentally spilled some rum on it, which gave the dish a more inviting scent and look, thus winning the royal palate. Inspired by Ali Baba, a character from One Thousand and One Nights, the sovereign named the delicacy after him. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The baba first arrived in Paris and then in Naples, together with the “monslù”, or chefs employed by Parthenopean [that is, Neapolitan] noble families, where it acquired its characteristic mushroom shape. I like to bake this cake in a round mould with a hole in the middle and to decorate it with little babàs along with some pastry cream or whipped cream, even though “true” Neapolitans consider such additions sacrilegious. | ||

| + | | źródło = {{Cyt | ||

| + | | nazwisko = Nuti | ||

| + | | imię = Carla | ||

| + | | tytuł = Una psicologa in cucina | ||

| + | | url = https://books.google.dk/books?id=Hq43aMpr7lsC&pg=PA107&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwjg55KNnrThAhWBpYsKHSgcA-0Q6AEIKjAA | ||

| + | | wydawca = Sovera Edizioni | ||

| + | | miejsce = Roma | ||

| + | | rok = 2011 | ||

| + | | strony = 107 | ||

| + | }}, own translation | ||

| + | | oryg = «Tu si nu babà!!!», complimento che i napoletani fanno alla loro ragazza per dirle che è amabile, bella, attraente e dolce. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Il babà, specialità prettamente napoletana, ha in realtà un’origine polacca. Si racconta che Stanislao Leszczinski (Re di Polonia), uomo molto goloso, un giorno, allontanando rabbiosamente il piatto contenente un dolce che amava poco, fece cadere su questo del rhum donandogli un profumo en un aspetto invitante, tanto de conquistare il palato del Re. Fu lo stesso Sovrano, inspirandosi ad Alì Babà, personaggio del libro “Le Mille e una Notte”, a dare il nome a questa leccornia. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Il babà arrivò prima a Parigi e poi a Napoli con i “monslù” (cuochi delle famiglie nobili partenopee), dove assunse la sua forma caratteristica a fungo. A me piace prepararlo tondo con il buco centrale, decorato con piccoli babà e servito con crema o panna montata. Questi sapori aggiunti, sono per i napoletani “veraci”, un vero sacrilegio. | ||

| + | }} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | Mr. Fabrizio Mangoni, “just like Stanislao, an urbanist and a gourmet”, as he describes himself, recounted the former Polish king’s alleged invention of the ''babà'' in even more colour: | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[File:Baba al rhum.jpg|thumb|Jars of Italian babàs drowned in rum or limoncello syrup]] | ||

| + | {{ Cytat | ||

| + | | The golden, wavy, spongy surface had just detached from the mould. It looked like something between a turban and a pagoda, an architecture with a new texture, built out of concentric circles growing smaller and smaller towards the top. Stanislao soon understood that he had found an answer to his own desires. It looked soft and was supple to the touch. Its fine texture and the scent it spread made it an absolute novelty. Even before tasting it, he knew that he had invented a dessert like no other in his land or in his times; a rare point of equilibrium between consistency and lightness. A bit like his own life. | ||

| + | |||

| + | This is the beginning of the long journey of the babà, a mythical dessert invented in the mid-18th century by Stanislao Lekzinsky [sic], ex-King of Poland and Duke of Lorraine at the time. A journey which has many links with the Orient. Stanislao had spent much time in Ottoman captivity and had the opportunity to study and sketch the architecture of that land, which would later inspire the pavilions decorating his ducal palace, along with an enormous theatre of automata. At first, the babà was dry, filled with sultana and Corinthian raisins, and, most importantly, it spread the scent of saffron. For its exoticism, the novelty of its taste and texture, Stanislao dubbed the dessert Ali Baba, in reference to One Thousand and One Nights, whose French translation he had read during his stay in the sultan’s prison in Constantinople. | ||

| + | | źródło = {{Cyt | ||

| + | | tytuł = Festival della letteratura di viaggio | ||

| + | | nazwisko r = Mangoni | ||

| + | | imię r = Fabrizio | ||

| + | | rozdział = I viaggi del Babà | ||

| + | | adres rozdziału = http://www.festivaletteraturadiviaggio.it/altrove/cibi/viaggi-del-baba.htm | ||

| + | | wydawca = Società Geografica Italiana Onlus | ||

| + | | miejsce = Roma | ||

| + | | rok = 2017 | ||

| + | }}, own translation | ||

| + | | oryg = La superficie dorata, a balze, spugnosa, si era appena staccata dalla forma. Ricordava qualcosa a metà tra il turbante e la pagoda, architettura di cerchi concentrici e digradanti verso l’alto, di una consistenza nuova. Che rispondesse ai suoi desideri Stanislao lo capì subito. Ne saggiò l’elasticità al tatto, e si presentava soffice. Il senso di morbidezza e il profumo che emanava ne facevano un’assoluta novità. Anche senza averlo ancora assaggiato, sapeva di aver inventato un dolce che non aveva niente a che vedere con gli altri della sua terra e della sua epoca; un raro punto di equilibrio tra consistenza e leggerezza. Un po’ come la sua vita. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Con queste parole si apre il racconto del lungo viaggio del Babà, un dolce mitico, inventato a metà del Settecento da Stanislao Lekzinsky, ex re di Polonia e al momento dell’invenzione duca di Lorena. Viaggio che presenta molti legami con l’Oriente. Stanislao era sto a lungo prigioniero dei turchi, e lì ha potuto studiare e disegnare le architetture di quella terra, che ispireranno più tardi lo stile dei Pavillons che decoreranno il suo palazzo ducale, insieme ad un enorme teatro di automi. Il babà, all’inizio era secco, aveva nell’impasto l’uvetta di Smirne e di Corinto e, soprattutto, portava il profumo dello zafferano. Per l’esotismo, la novità del sapore e della consistenza del dolce Stanislao decise di chiamarlo l’Alì Babà, in omaggio alle Mille e Una Notte, il cui testo francese aveva potuto leggere proprio durante il suo soggiorno – prigione presso il Sultano di Costantinopoli. | ||

}} | }} | ||

| − | {{ | + | How much of all that is true? Should Stanislao really get the credit for inventing the rum baba and does its name really come from a fairy-tale Arab craftsman who robbed the forty thieves of their sesame treasure? As you can see from the quotations above, the first stop on our journey to unravel this mystery is going to be in France. |

| − | | | + | |

| + | == Babaorum == | ||

| + | [[File:Babaorum.jpg|thumb|upright|Roman Gaul ca. 50 BCE according to Goscinny and Uderzo]] | ||

| + | According to one popular publication about the history of France, the rum baba dates back all the way to antiquity. The French term for this dessert, ''baba au rhum'' may have come from the name of a Roman military camp called Babaorum. In Julius Caesar’s time, it was one of the four Roman camps surrounding the last independent Gaulish village in Armorica. The other three were called Laudanum, Petibonum and Aquarium.<ref>{{Cyt | ||

| + | | nazwisko = Goscinny | ||

| + | | imię = René | ||

| + | | nazwisko2= Uderzo | ||

| + | | imię2 = Albert | ||

| + | | tytuł = Astérix : Le Combat des chefs | ||

| + | | wydawca = Hachette | ||

| + | | miejsce = Paris | ||

| + | | rok = 2013 | ||

| + | | strony = 3 | ||

| + | }}</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Yet a different source, ''Larousse Gastronomique'', the Bible of French cuisine, confirms the story of King Stanislas inventing the baba and naming it after a character from an Arabic fairy tale. | ||

| + | |||

| + | {{ Cytat | ||

| + | | Baba, a cake made from leavened dough that contains raisins and is steeped, after baking, in rum or kirsch [Alsatian cherry liqueur] syrup. {{...}} The origin of this cake is attributed to the greediness of the Polish king Stanislas Leszcsynski [sic], who was exiled in Lorraine. He found the traditional kouglof [Alsatian bundt cake] too dry and improved it by adding rum. As a dedicated reader of the Thousand and One Nights, he is said to have named this creation after his favourite hero, Ali Baba. This recipë was a great success at the court of Nancy [capital of Lorraine], where it was usually served with a sauce of sweet Málaga wine. {{...}} Sthorer [sic], a pastrycook who attended the court of the Polish king, perfected the recipë using a brioche steeped in alcohol; he made it the speciality of his house in the Rue Montorgueil in Paris and called it ‘baba’. | ||

| źródło = {{Cyt | | źródło = {{Cyt | ||

| + | | inni = ed. Joël Robuchon | ||

| + | | tytuł = Larousse Gastronomique | ||

| + | | wydawca = Hamlyn | ||

| + | | rok = 2009 | ||

| + | | strony = 51 | ||

| + | }} }} | ||

| + | |||

| + | As we shall see, ''Larousse Gastronomique'' isn’t much more reliable than ''Astérix'' as a source of historical knowledge. After all, why would Stanislas take an Alsatian ''kouglof'' and steep it in Alsatian ''kirsch'' while staying in Lorraine? Was this recipë really developed by the king himself or rather by one of his pastrycooks, such as the aforementioned Stohrer? And most importantly, why would a Pole name a cake after some Arab guy, if the word ''“baba”'' had already meant “bundt cake” in his own native language for centuries? | ||

| + | |||

| + | It looks like we need to take a closer look at this King Stanislas and his relation to the ''baba''. You could shoot a few action movies based on his biography, but I will do my best to recap his life and his times as succinctly as possible. | ||

| + | |||

| + | == A King-in-Exile == | ||

| + | [[File:Uczta koronacyjna Stanisława Leszczyńskiego.jpg|thumb|upright|left|King Stanislas’s coronation banquet]] | ||

| + | Poland entered the 18th-century as a great power in decline, under King Augustus II of House Wettin, who also ruled the Electorate of Saxony, a relatively small, but rich, state in what is now eastern Germany. Just before the end of the previous century (1698), Augustus was visited by Tsar Peter the Great of Russia, on his way back from his grand survey of Europe. Both monarchs were unusually tall, strong and able to consume copious amounts of alcohol. So when they met, they engaged in a several-day-long bout of binge drinking punctuated with cannon-shooting and bare-handed-horseshoe-breaking contests. And, while they were at it, they also decided to wage war against Sweden. A coalition of Saxon, Russian and Danish forces attacked the mighty Baltic empire soon afterwards (1700). But, like many other drunken ideas, it didn’t go exactly as intended. The Swedes smashed the Danes in Zealand, the Russians at Narva and the Saxons on the Daugava, and then proceeded to invade Poland. Polish senators tried to explain to King Charles XII of Sweden that Augustus was at war with him as Elector of Saxony rather than as King of a neutral Poland, but to no avail. The Swedes soon captured Vilno, Warsaw, Poznań and Cracow (1702), and Charles started looking around to find Poland a new king. His first choice was James Sobieski, the eldest son of the previous king, but Augustus had him imprisoned in Saxony (1704). | ||

| + | |||

| + | Anti-Saxon opposition in Poland sent a delegation to the king of Sweden, headed by the Palatine of Poznań, Stanisław Leszczyński{{czyt|Stanisław Leszczyński}}. King Charles was so charmed by the young, handsome, well-read and eloquent palatine, that he decided to make him his own puppet on the Polish throne. The royal election of 1705 – the first in Polish history to be conducted in the presence of foreign troops – was widely considered a farce, but it did dutifully elect the 28-year-old Leszczyński as the dethroned Saxon’s successor. He was crowned (in Warsaw rather than in Cracow, the traditional coronation site) with a crown which Charles had lent him for the ceremony and took back just afterwards. The reign of Stanisław I lasted no longer than four years. The situation changed dramatically when the Russians crushed the Swedish army at Poltava (1709), forcing King Charles into exile in the Ottoman Empire. Augustus got his Polish throne back, while Stanisław ran to the Swedish city of Stettin (now Szczecin, Poland) and thence to the Ottoman Empire, to consult further plans with Charles. | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[File:Colin Stanislas Ier.jpg|thumb|upright|Stanislas I, King of Poland, Duke of Lorraine and Bar, in the autumn of his years]] | ||

| + | Bender, a town in what is now Transnistria (between Moldova and Ukraine), was where King Charles stayed for a few years after Poltava and the only place in the Ottoman Empire where Stanisław spent any amount of time. He never was in Constantinople, let alone in an Ottoman prison. Eventually (1714), Charles gave him the Swedish-owned Duchy of Two Bridges (now Zweibrücken, Germany), where the former Polish king, inspired by Ottoman architecture, built himself a little palace he called Tschifflik (from Turkish ''“çiftlik”'', or “farm”). Unfortunately, Stanisław had to move out after his Swedish protector passed away (1718), so he moved to a modest palace in nearby Wissembourg. It’s a town in Alsace, a border region which by that point had belonged to France for almost forty years, but was still mostly German-speaking (Alsace would later change hands between Germany and France like a ping pong ball, eventually staying with the latter). Maybe Stanisław would have stayed there for the rest of his life, if not for an unexpected visit by matchmakers from Versailles, who asked him for his daughter’s hand in the name of King Louis XV of France. And so Princess Marie Leszczyńska married Louis, seven years her junior, and proved to be a perfect wife (she would give him ten children without getting much in the way of his many extramarital liaisons), while her parents, who wanted to be closer to their only living daughter, moved into Chambord, one of the most luxurious ''châteaux'' of the Loire Valley. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Meanwhile, back in Poland, Augustus II continued to reign until he ended his gluttonous life by dying from gangrene after diabetic foot amputation (1733). Stanisław, counting on his son-in-law’s support, decided it was a good occasion to try and win back the Polish throne. He travelled incognito back to Warsaw, where he made his sudden appearance on the election field and was chosen – legally, this time – as king of Poland. His earlier coronation was retroactively declared valid, so there was no need to repeat it. However, the history from almost thirty years before repeated itself in reverse – foreign troops, Russian this time around, captured Praga, the eastern suburb of Warsaw, where they arranged a rival election of Augustus II’s son, soon afterwards crowned in Cracow as King Augustus III. Stanisław escaped from Warsaw to Danzig (Gdańsk), a city which managed to hold out against a Russian siege for some time. A network of alliances covering Europe transformed the fight for the Polish throne into a major international conflict, which – despite being known as the War of the Polish Succession – was fought out mostly in Italy and on the banks of the Rhine. France was quick to capture Lorraine (another border region), but (except for a small and unsuccessful landing operation in Westerplatte near Danzig) did little to help Stanisław keep his crown. In the end, Danzig fell to the Russians and Stanisław, disguised as a peasant, escaped (once again) to Königsberg (now Kaliningrad, Russia). | ||

| + | |||

| + | The war ended with Augustus III staying on the Polish throne. As a consolation prize, Louis XV gave his dad-in-law the Duchy of Lorraine and Bar (1737), where Leszczyński lived out his years while still being addressed as “king” and where, in the words of Voltaire, he was “able to do more good than all the Sarmatian [that is, Polish] kings ever managed to do on the banks of the Vistula.”<ref>{{Cyt | ||

| nazwisko = Voltaire | | nazwisko = Voltaire | ||

| inni = trans. Robert M. Adams, ed. Nicholas Cronk | | inni = trans. Robert M. Adams, ed. Nicholas Cronk | ||

| Line 16: | Line 104: | ||

| wydawca = W.W. Norton & Company | | wydawca = W.W. Norton & Company | ||

| rok = 2016 | | rok = 2016 | ||

| − | }} | + | }}</ref> Lorrainers still remember Leszczyński as King Stanislas the Good (''Stanislas le Bienfaisant''), even though he earned this moniker largely due to the “good tsar, bad boyars” principle, finally living his dream of reigning as a charitable enlightened monarch surrounding himself with artists and philosophers, while leaving the day-to-day chores of running the government to his French chancellor, the widely hated Marquis de La Galaizière. |

| + | |||

| + | Although Stanislas and the Wettins of Saxony were fierce political rivals, they were united in their love of good food, sweets, wine and women. In Poland, the reign of Augustus III finally brought a period of long-sought peace, now known as the “Saxon Carnival”, when the Polish nobility lived out the proverb: | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[File:Baba au rhum chez roi Stanislas.jpg|thumb|upright|A ''baba au rhum'' being devoured at the court of King Stanislas at Lunéville. Still from Arnaud Sélignac’s 2007 biopic ''Divine Émilie''.]] | ||

| + | {{Cytat | ||

| + | | <poem>Under a Saxon king, | ||

| + | Loosen your belt to eat and drink!</poem> | ||

| + | | źródło = Polish saying (18th century), own translation | ||

| + | | oryg = <poem>Za króla Sasa | ||

| + | Jedz, pij i popuszczaj pasa!</poem> | ||

| + | }} | ||

| + | |||

| + | Meanwhile, Stanislas, in his “little Versailles” at Lunéville, hosted Voltaire, Rousseau and Montesquieu, enjoyed the theatre of automata in his exotic gardens and stuffed his face with fantastic creations sculpted from sugar and ice cream by his court confectioner Joseph Gillers. He got terribly fat, yet still outlived Augustus III; he chose not to fight for the Polish throne again, though, leaving Empress Catherine the Great of Russia to pick his namesake, Stanisław Poniatowski, as Poland’s new (and last) king (1764). | ||

| + | |||

| + | One of the shortest-reigning kings of Poland, but also the longest-lived, died a particularly nasty death. It’s said that he wanted to light his pipe or that he just plunged himself in deep thought next to a fireplace; but pissing into the fireplace wasn’t unusual at all back then, especially for elderly monarchs who didn’t always feel like walking all the way to the outhouse. In any case, his clothes caught fire and the former king died from severe burns after a few days of agony. | ||

| + | |||

| + | '''''TL;DR:''''' Stanisław Leszczyński was a king of Poland, then he was exiled, lived in Alsace for some time, then he became king of Poland and got exiled all again, and spent the rest of his life as duke of Lorraine and a great gourmet. But so far, we haven’t learned anything new about the ''baba''. | ||

| + | |||

| + | == Baba, baby == | ||

| + | {{Video|url=https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xvXyhC27buU|szer=300|poz=right|opis=Eugeniusz Bodo singing ''“Ach te baby”'' in Michał Waszyński’s 1933 film ''Zabawka'' (''Toy'')}} | ||

| + | The Polish word ''“baba”'' is unusually rich in meanings. In its original Proto-Slavic sense, it refers to a grandmother or, by extension, any elderly lady. In old Polish, the same word was used for any peasant woman and is still used to describe an uncouth, boorish hag. Other meanings include “female street vendor”, “herbalist”, “midwife” and “witch” (as in the most famous Slavic witch, Baba Yaga). A ''“baba”'' may even refer to a married or widowed woman of any age, as in ''“moja baba”'', or “my wife”. You can use the diminutive form, ''“babka”'', for a young and attractive woman, much like the ''“babà”'' in the Neapolitan dialect of Italian. But don’t overdo it, because if you diminutize the word even further, you’re gonna get a ''“babcia”'', or “granny”.<ref>{{Cyt | ||

| + | | inni = ed. Piotr Żmigrodzki | ||

| + | | tytuł = Wielki Słownik Języka Polskiego | ||

| + | | rozdział = Baba | ||

| + | | adres rozdziału = https://www.wsjp.pl/do_druku.php?id_hasla=50227&id_znaczenia=0 | ||

| + | | wydawca = Instytut Języka Polskiego PAN | ||

| + | }}</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | In Polish grammar, the plural and genitive form of ''“baba”'' is ''“baby”''{{czyt|baby}} (pronounced: ''bah-bih'', not ''bay-bee''). You can sometimes see in Poland some half-translated labels, like ''“żel do mycia baby”'', which was probably meant to say “baby-washing gel”, but actually says “crone-washing gel”. When interwar Poland’s top heart-throb Eugeniusz Bodo sang ''“ach te baby”'' in the 1930s, he wasn’t addressing his one and only baby; he meant all women in general. Or did he mean the cakes? | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[File:Adam Setkowicz.jpg|thumb|left|upright=.6|A Polish girl carrying an Easter ''baba'', visually extended by her pleated skirt (1936)]] | ||

| + | {{ Cytat | ||

| + | | <poem>Lovely “baby”, oh these “baby”! | ||

| + | One could eat them with a spoon.</poem> | ||

| + | | źródło = Jerzy Nel, ''Ach te baby'' (1933), own translation | ||

| + | | oryg = <poem>Kochane baby, ach te baby! | ||

| + | Człek by je łyżkami jadł.</poem> | ||

| + | }} | ||

| + | |||

| + | So which of these multiple meanings gave rise to ''“baba”'', the bundt cake? Did the cake use to resemble a [https://www.google.com/search?q=baby+kamienne&tbm=isch pagan stone idol,] which is also called ''“baba”'' in Polish? Or does the cake’s name come from its resemblance to a peasant woman’s long pleated skirt? Or perhaps it comes from the fact that it’s always been old women who were most experienced in the tricky art of yeast-cake baking? | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[File:Michał Elwiro Andriolli, Kłopoty wielkanocne.jpg|thumb|These ''baby'' (women) let a man into the kitchen and now their ''baba'' (cake) has flopped.]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | After all, baking a beautiful, tall, airy ''baba'' was one of the most demanding tasks Polish home cooks ever had to face. Great care was needed to prevent the cake from sinking or browning a little too much. A housewife who aimed for the perfect ''baba'' had to start by choosing the best ingredients – high-quality wheat flour, good beer yeast and fresh butter. The oven had to be heated as much as possible, so that it could keep a constant temperature for a long time. The moulds had to be perfectly clean before being filled with dough and popped into the oven. Then came the almost magical practices whose goal was to prevent the ''baba'' from “catching a cold” and falling. Doors and windows were sealed to avoid draughts, women walked on their toes and talked in whispers when close to the oven, and finally, the ''baba'' was gently placed on down pillows for cooling. And, of course, no men were allowed in the kitchen; the baking of a ''baba'' was a ''baby''-only affair.<ref>{{Cyt | ||

| + | | nazwisko = Łozińska | ||

| + | | imię = Maja | ||

| + | | nazwisko2= Łoziński | ||

| + | | imię2 = Jan | ||

| + | | tytuł = Historia polskiego smaku: Kuchnia, stół, obyczaje | ||

| + | | wydawca = Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN | ||

| + | | miejsce = Warszawa | ||

| + | | rok = 2012 | ||

| + | | strony = 173–174 | ||

| + | }}</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | In any case, the word ''“baba”'' was used in the sense of “bundt cake” at least as early as the 17th century,<ref>{{Cyt | ||

| + | | inni = ed. Włodzimierz Gruszczyński | ||

| + | | tytuł = Elektroniczny słownik języka polskiego XVII i XVIII wieku | ||

| + | | rozdział = Baba | ||

| + | | adres rozdziału = https://sxvii.pl/index.php?strona=haslo&id_hasla=1295 | ||

| + | | wydawca = Instytut Języka Polskiego PAN | ||

| + | | miejsce = Warszawa | ||

| + | }}</ref> so it’s hard to guess why Stanislas would have had to reinvent the word from Ali Baba. | ||

| + | |||

| + | == From Stohrer to Savarin == | ||

| + | [[File:Nos petits Alsaciens chez eux; notes et souvenirs d{{'}}artiste, par P. Kauffmann; (1918) (14566626019).jpg|thumb|upright|Alsatian girls carrying a ''Kugelhopf'' on Three Kings Day]] | ||

| + | While the word ''“baba”'' is without a doubt of Slavic origin (so there’s never been a need to borrow it from Arabic), there is no reason to believe that a turban-shaped yeast cake is a native Polish, or generally Slavic, invention. The same kind of cake has been known, under various names, throughout central Europe, from the Netherlands, to Alsace, Germany, Switzerland, Austria, the Czech lands, Poland, to Russia. In German-speaking territories it’s known as ''“Gugelhupf”'' or ''“Kugelhupf”''. The ''Kugelhupf'' didn’t always have to be sweet, as evidenced by the tradition of former eastern Poland, where they still bake a potato casserole with onions and bacon (the Jews make it too, but without the bacon) and call it “potato ''babka”, “kugel”, “kugiel”'' or ''“kugelis”''. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The origin of this German name is even more mysterious than that of the Polish ''“baba”''. ''“Kugel”'' means “a ball” in modern German, but the cake was never baked in such a shape. Perhaps ''“Gugel”'' comes from Latin ''“cucullus”'', or “a hood”, while ''“Hupf”'' is the equivalent of “hop” (as in jumping)? But what would a jumping hood have to do with a bundt cake? According to a pair of famous German etymologists, brothers Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm (who also collected German folk tales as part of their linguistic studies), a yeast cake would grow so fast that it jumped, but it’s possible that what they recorded was just folk etymology. Or maybe it has something to do with prancing around at weddings, where bundt cakes were often served? | ||

| + | |||

| + | This kind of cake was especially popular in Alsace, particularly on special occasions, such as weddings or the Three Kings Day (Epiphany). The Alsatians have come up with some legends to explain the name of this cake, known as ''“Kugelhopf”'' in the local dialect of German. According to one legend, it was invented by an Alsatian priest, whose name was Gérard Kugelhopf.<ref>{{Cyt | ||

| + | | nazwisko = Krondl | ||

| + | | imię = Michael | ||

| + | | tytuł = Sweet Invention: A History of Dessert | ||

| + | | wydawca = Chicago Review Press | ||

| + | | rok = 2011 | ||

| + | | strony = 173 | ||

| + | | url = https://books.google.dk/books?id=Dt0RErSFvE8C&lpg=PA171&pg=PA17 | ||

| + | }}</ref> A more interesting legend claims that it was the Three Kings (or Magi) themselves who stopped on their way from the Holy Land to Cologne (where their alleged relics are still held) in the picturesque Alsatian town of Ribeauvillé. There, they stayed in the house of a local baker named Kugel and showed their gratitude by giving him a recipë for a yeast cake, which he would later make in the shape of their turbans.<ref>{{Cyt | ||

| + | | nazwisko = Perrier-Robert | ||

| + | | imię = Annie | ||

| + | | tytuł = Dictionnaire de la gourmandise | ||

| + | | rozdział = Kugelhopf | ||

| + | | adres rozdziału = https://books.google.dk/books?id=gk2xWRx5sgIC&lpg=PT242&pg=PT816 | ||

| + | | wydawca = Robert Laffont | ||

| + | | miejsce = Paris | ||

| + | | rok = 2012 | ||

| + | }}</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[File:Stohrer Paris.jpg|thumb|left|Inside the Stohrer pastry shop in Paris]] | ||

| + | And so we may finally solve the riddle. During his stay in Alsace (between his two stints as king of Poland), Stanislas employed local chefs, pantlers and pastrycooks. It’s quite likely that from time to time they served him some Alsatian specialities, including the ''Kugelhopf'', and that he couldn’t fail to notice that it’s actually the same thing as the Polish ''baba''. The best-known pastrycook to have begun his career at Stanislas’s court was Nicolas Stohrer (1706 – ca. 1781),<ref> {{Cyt | ||

| + | | nazwisko = Goldstein | ||

| + | | imię = Darra | ||

| + | | tytuł = The Oxford Companion to Sugar and Sweets | ||

| + | | nazwisko r = Field | ||

| + | | imię r = Elizabeth | ||

| + | | rozdział = Stohrer, Nicolas | ||

| + | | adres rozdziału = https://books.google.de/books?id=jbi6BwAAQBAJ&lpg=PA312&pg=PA657 | ||

| + | | wydawca = Oxford University Press | ||

| + | | rok = 2015 | ||

| + | | strony = 657 | ||

| + | }}</ref> whom Princess Marie took with her to Versailles when she became Queen of France. For the young Stohrer this meant the best bullet point on his resumé he could have ever dreamed of, but it also gave him the opportunity to popularize the pastry from his home region at the French royal court. The only problem was the cake’s German name, which the French found unpronounceable and unspellable; if the French absolutely have to write that word down, they come up with at least as many different ways to spell it (''cougloff, goglopf, gouglouff, guglhupf, kougelhopf, kouglhupf, kouglof,'' etc.) as they have ways to spell Leszczyński’s surname. So instead of calling the cake by its German name, Stohrer presented it to the French as ''baba'', the name he had learned from his Polish employer.<ref>M. Krondl, ''op. cit.'', s. 171</ref> The new word started to crop up in French texts half a century later, including in a letter from Denis Diderot, a co-author of the ''Encyclopédie'', to his lover, in which he described the banquets held by the Baron d’Holbach in his Grand-Val castle in southern France (quite far away from Alsace, Lorraine and Versailles): | ||

| + | {{clear}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | {{ Cytat | ||

| + | | I’m going to pass another week here. Pray to God that I don’t die from indigestion. Every day, they bring us from Champigny the most furious and most perfidious eels, and then little watermelons from Astrakhan, and then sauerkraut, and then partridges with cabbage, and then young partridges à la crapaudine, and then babas, and then pies, and then tarts, and then you would need twelve stomachs [to eat all that…] Fortunately, we drink in proportion, so it all goes well. | ||

| + | | źródło = {{Cyt | ||

| + | | inni = ed. J. Assézat, Maurice Tourneux | ||

| + | | tytuł = Œuvres complètes | ||

| + | | nazwisko r = Diderot | ||

| + | | imię r = Denis | ||

| + | | rozdział = Lettres à Sophie Volland, CVI: Au Grandval, le 24 septembre 1767 | ||

| + | | adres rozdziału = https://fr.wikisource.org/wiki/Page:Diderot_-_%C5%92uvres_compl%C3%A8tes,_%C3%A9d._Ass%C3%A9zat,_XIX.djvu/256 | ||

| + | | wydawca = Garnier | ||

| + | | miejsce = Paris | ||

| + | | tom = 29 | ||

| + | | rok = 1876 | ||

| + | | strony = 246 | ||

| + | }}, own translation | ||

| + | | oryg = J’ai encore huitaine à passer ici. Priez Dieu que je ne meure pas d’indigestion. On nous apporte tous les jours de Champigny les plus furieuses et les plus perfides anguilles, et puis des petits melons d’Astracan, puis de la sauerkraut, et puis des perdrix aux choux, et puis des perdreaux à la crapaudine, et puis des baba, et puis des pâtés, et puis des tourtes, et puis douze estomacs qu’il faudrait avoir {{...}} Heureusement on boit en proportion, et tout passe. | ||

| + | }} | ||

| + | |||

| + | Somehow, along the way, ''“baba”'' has lost its original feminine gender and its association with women, becoming a masculine noun in both French (''“le baba”'') and, later, Italian (''“il babà”''), which may explain how the Ali Baba connection may have seemed plausible to non-Slavs. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In 1730, Stohrer decided to start his own business, so he opened – next to the northern coach terminus in Paris, at Mont Orgueilleux (now 51, Montorgueil Street) – [https://stohrer.fr/en the oldest Parisian pastry shop still in operation.] Did he sell ''babas / kouglofs'' there? Most probably. Were they imbibed with rum? Probably not, at least not from the start. 18th-century sources are quite unanimous in describing the ''baba'' as coloured with saffron and studded with raisins, without any mention of rum. At the beginning of the 19th century, the great gourmet Grimod de La Reynière would already attribute the baba to Stanislas, but it still wasn’t the rum baba. | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[File:Baba zwyczajna.jpg|thumb|upright|A regular Polish ''baba''<br />From [https://polona.pl/item/dra-oetkera-przepisy-dla-skrzetnych-gospodyn,MTY0MjkxNDA/20/#item a collection of pastry recipës] published in the 1930s by a Dr. Oetker factory in Oliva, Free City of Danzig (now part of Gdańsk, Poland)]] | ||

| + | {{ Cytat | ||

| + | | The baba is a Polish dish invented by Stanislas Leczinski [sic], King of Poland and Grand [sic] Duke of Lorraine and Bar, a great gourmet towards the end of his days, who was no stranger at all to culinary practice. Saffron and Corinthian raisins are the principal seasonings of the baba, but few cooks know how to make it well. | ||

| + | | źródło = {{Cyt | ||

| + | | nazwisko = Reynière | ||

| + | | imię = Alexandre-Balthazar-Laurent Grimod de La | ||

| + | | tytuł = Manuel des amphytrions | ||

| + | | url = https://books.google.pl/books?id=vAs9QwAACAAJ&pg=PA170 | ||

| + | | wydawca = Capelle et Renard | ||

| + | | miejsce = Paris | ||

| + | | rok = 1808 | ||

| + | | strony = 170 | ||

| + | }}, own translation | ||

| + | | oryg = Le baba est un met polonais, de l’invention de Stanislas Leczinski, Roi de Pologne, et Grand-Duc de Lorraine et Bar, prince fort gourmand vers la fin de ses jours, et qui n’étoit point étragner à la pratique de la cuisine. Le safran et les raisins de Corinthe sont les principaux assaisonnements du baba, mais peu de cuisiniers savent bien le faire. | ||

}} | }} | ||

| + | |||

| + | In pre-revolutionary France, rum was rare anyway, mostly due to high custom duties, imposed to protect the producers of domestic brandies and other alcohols. It was only at the beginning of the 19th century that the French learned to appreciate the English punch, which was made from Caribbean sugar-cane rum. In the 1840s, rum started to appear in French dessert recipës. And so the tasty legend of a Polish king who soaked a dry ''kouglof'' in rum and named it after a fairy-tale protagonist, falls apart like a house of cards. Mr. Michael Krondl, a food historian, has put it best: | ||

| + | |||

| + | {{ Cytat | ||

| + | | The French love to tell anecdotes about their food, and if some eminent person can be attached to a dish, so much the better. Some of the tales happen to be true, many are made up, but in some cases the stories are like a napoleon or millefeuille made up of layers of crisp fact and frothy fiction. Pulling it apart neatly is almost impossible. What’s more, once you’ve scraped away all the fluff, the truth you are left with can be a little dry. | ||

| + | | źródło = {{Cyt | ||

| + | | nazwisko = Krondl | ||

| + | | imię = Michael | ||

| + | | tytuł = Sweet Invention: A History of Dessert | ||

| + | | wydawca = Chicago Review Press | ||

| + | | rok = 2011 | ||

| + | | strony = 171 | ||

| + | | url = https://books.google.dk/books?id=Dt0RErSFvE8C&lpg=PA171&pg=PA17 | ||

| + | }} | ||

| + | }} | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[File:{{#setmainimage:Baba czekoladowa.jpg}}|thumb|upright|A Polish chocolate ''baba''<br />The Dr. Oetker factory in Oliva is still operational, with the characteristic cloying scent of powdered milk wafting off its premises. I live 400 metres away from it, so I know.]] | ||

| + | Soaking individual helpings of dry cake in wine, coffee or chocolate is surely an old practice, but it’s not the same as soaking an entire bundt cake prior to serving. Whose idea was it then? We don’t know. We do know, however, that in 1845 Auguste Julien, a co-owner of a pastry shop at Place de la Bourse in Paris, expanded his offer by introducing small babas with candied orange zest instead of raisins and imbibed with rum (or kirsch)-based syrup. And because, as we already know, the French prefer those dishes that they can associate with celebrities, he named this new kind of baba ''“savarin”''<ref>M. Krondl, ''op. cit.'', p. 172</ref> – after the famous gourmet Jean-Anthelme Brillat, who changed his name to Savarin (or was it his father?), so that he could inherit his aunt’s property.<ref>{{Cyt | ||

| + | | inni = ed. Joël Robuchon | ||

| + | | tytuł = Larousse Gastronomique | ||

| + | | rok = 1997 | ||

| + | | strony = 141 | ||

| + | | url = https://archive.org/details/DictionnaireLarousseGastronomique/page/n76 | ||

| + | }}</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | As for the distinctive shape of the ''baba'' or ''Gugelhupf'', sometimes also known the “Turk’s head”, such moulds were already used by the Romans ca. 200 CE.<ref>{{Cyt | ||

| + | | nazwisko = Adamson | ||

| + | | imię = Melitta Weiss | ||

| + | | tytuł = Food in Medieval Times | ||

| + | | url = https://books.google.de/books?id=jtgud2P-EGwC&lpg=PP1&pg=PA69 | ||

| + | | wydawca = Greenwood Press | ||

| + | | rok = 2004 | ||

| + | | strony = 69 | ||

| + | }}</ref> Which means that history came full circle, from ancient Rome, via Germany, Poland, Alsace, France and back to Italy and the Neapolitan ''babà al rum''. | ||

| + | |||

| + | == Recipë == | ||

| + | History also came full circle when recipës for Polish ''baby'' came back to Poland, but “improved” by the addition of alcohol-laced syrup. Here’s one, with arak-based punch, rather than rum, added to the dough before baking: | ||

| + | |||

| + | {{ Cytat | ||

| + | | '''Ordinary punch''': Soak one pound of sugar in water, but first use it to scrape the zest of six lemons, put it immediately into a pot and boil into syrup; pour a quart of arak and then the juice squeezed from the six lemons into the syrup; keep under cover for some time, then pour the [punch] essence into a bottle {{...}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | '''Punch babas''': Mix two pounds of fine flour with a quart of lukewarm milk and 4 tablespoons of thick yeast, add 10 whole eggs and a quarter of a pound of sugar; leave in a warm place for the night; in the morning, add a pound of lukewarm pre-melted butter and half a quart of punch essence. Knead the dough thoroughly, baste small moulds with fresh butter, half-fill them with the dough; after the dough has risen, put them into a medium-heated oven for three quarters. Remove from moulds while hot. | ||

| + | | źródło = {{Cyt | ||

| + | | nazwisko = L[eśniew]ska | ||

| + | | imię = Bronisława | ||

| + | | tytuł = Kucharz polski jaki być powinien: książka podręczna dla ekonomiczno-troskliwych gospodyń | ||

| + | | url = https://polona.pl/item/kucharz-polski-jaki-byc-powinien-ksiazka-podreczna-dla-ekonomiczno-troskliwych-gospodyn,MzU1NTg1Nw/187 | ||

| + | | wydawca = S.H. Merzbach | ||

| + | | miejsce = Warszawa | ||

| + | | rok = 1856 | ||

| + | | strony = 368, 424 | ||

| + | }}, own translation | ||

| + | | oryg = '''Poncz zwyczajny''': Funt cukru umoczyć w wodzie, poprzednio jednak trzeba go obetrzeć o skórkę 6 cytryn, włożyć natychmiast w rondelek i zagotować na syrop; mając już wyciśnięty i sok z 6 cytryn, wlać do syropu najprzód kwartę araku, a potem sok cytrynowy, potrzymać tak pod przykryciem, wtedy zlać esencję do butelki {{...}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | '''Babki ponczowe''': Dwa funty pięknej mąki zarobić kwaterką letniego mleka, 4 łyżkami albo łutami gęstych drożdży, dodać 10 jaj całych i ćwierć funta cukru; zostawić w ciepłym miejscu pod przykryciem na noc; a nazajutrz rano, dodać funt przetopionego letniego masła i półkwaterek esencji ponczowej. Wyrobić ciasto dokładnie, małe foremki wysmarować świeżym masłem, napełnić do połowy ciastem, po chwili rośnienia, wsadzić w piec umiarkowany na 3 kwadranse. Wyjąć z foremek na gorąco. | ||

| + | }} | ||

| + | |||

| + | {{Przypisy}} | ||

| + | {{Nawigacja|poprz=A Royal Banquet in Cracow|nast=A Barrel of Beer for the Benedictine Brothers}} | ||

| + | {{Komentarze}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Category: Arak]] | ||

| + | [[Category: Baba]] | ||

| + | [[Category: Kirsch]] | ||

| + | [[Category: Millefeuille]] | ||

| + | [[Category: Limoncello]] | ||

| + | [[Category: Punch]] | ||

| + | [[Category: Rum]] | ||

| + | [[Category: Savarin]] | ||

| + | [[Category: Augustus II]] | ||

| + | [[Category: Augustus III]] | ||

| + | [[Category: Jean-Anthelme Brillat-Savarin]] | ||

| + | [[Category: Denis Diderot]] | ||

| + | [[Category: Joseph Gillers]] | ||

| + | [[Category: Alexandre-Balthazar-Laurent Grimod de La Reynière]] | ||

| + | [[Category: Stanisław Leszczyński]] | ||

| + | [[Category: Marie Leszczyńska]] | ||

| + | [[Category: Bronisława Leśniewska]] | ||

| + | [[Category: Louis XV]] | ||

| + | [[Category: Peter the Great]] | ||

| + | [[Category: Nicolas Stohrer]] | ||

| + | [[Category: Vladislaus IV Vasa]] | ||

| + | [[Category: Voltaire]] | ||

| + | [[Category: Naples]] | ||

| + | [[Category: Paris]] | ||

| + | [[Category: Alsatians]] | ||

| + | [[Category: Ancient Romans]] | ||

| + | [[Category: Antiquity]] | ||

| + | [[Category: Early Modern Period]] | ||

| + | [[Category: Recipës]] | ||

| + | [[Category: Warsaw]] | ||

| + | [[Category: Cracow]] | ||

| + | [[Category: Szczecin]] | ||

| + | [[Category: Italy]] | ||

| + | [[Category: Turkey (country)]] | ||

| + | [[Category: Russia]] | ||

| + | [[Category: Germany]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[pl: Stanisław Leszczyński i czterdziestu rozbójników]] | ||

Latest revision as of 17:46, 11 May 2024

Easter season is here, which is a good occasion to write something about the baba, a tall, rich yeast cake traditionally served in Poland for Easter breakfast. But before we move on to the Polish baba, let’s take a look at the babà al rum, which the Neapolitans consider their unique regional speciality.

Si ’nu babà

A babà al rum is a kind of oversized cupcake that is baked, usually more than one at a time, in a can-shaped mould so that the dough rises over the edge to form a mushroom-like shape. Once it’s done, removed from the mould and allowed to cool down, the babà is soaked in syrup mixed with some rum (hence the al rum in the name) or limoncello (local lemon liqueur). Neapolitans prize this delicacy so much that the word babà has become a synonym for anything or anyone that is particularly sweet and attractive. This is what Ms. Carla Nuti, an Italian psychologist who describes human personalities by comparing them with desserts, has to say about the origin of the babà and its name:

| “Tu si nu babà!” [literally: you are a baba!] is a compliment Neapolitans use to tell their girlfriends that they are lovely, beautiful, attractive and sweet.

The babà, a truly Neapolitan speciality, is in fact of Polish origin. Stanislao Leszczinski [sic], King of Poland and a great gourmet, is said to have one day angrily pushed away a dessert he wasn’t fond of and to have accidentally spilled some rum on it, which gave the dish a more inviting scent and look, thus winning the royal palate. Inspired by Ali Baba, a character from One Thousand and One Nights, the sovereign named the delicacy after him. The baba first arrived in Paris and then in Naples, together with the “monslù”, or chefs employed by Parthenopean [that is, Neapolitan] noble families, where it acquired its characteristic mushroom shape. I like to bake this cake in a round mould with a hole in the middle and to decorate it with little babàs along with some pastry cream or whipped cream, even though “true” Neapolitans consider such additions sacrilegious. | ||||

— Carla Nuti: Una psicologa in cucina, Roma: Sovera Edizioni, 2011, p. 107, own translation

Original text:

|

Mr. Fabrizio Mangoni, “just like Stanislao, an urbanist and a gourmet”, as he describes himself, recounted the former Polish king’s alleged invention of the babà in even more colour:

| The golden, wavy, spongy surface had just detached from the mould. It looked like something between a turban and a pagoda, an architecture with a new texture, built out of concentric circles growing smaller and smaller towards the top. Stanislao soon understood that he had found an answer to his own desires. It looked soft and was supple to the touch. Its fine texture and the scent it spread made it an absolute novelty. Even before tasting it, he knew that he had invented a dessert like no other in his land or in his times; a rare point of equilibrium between consistency and lightness. A bit like his own life.

This is the beginning of the long journey of the babà, a mythical dessert invented in the mid-18th century by Stanislao Lekzinsky [sic], ex-King of Poland and Duke of Lorraine at the time. A journey which has many links with the Orient. Stanislao had spent much time in Ottoman captivity and had the opportunity to study and sketch the architecture of that land, which would later inspire the pavilions decorating his ducal palace, along with an enormous theatre of automata. At first, the babà was dry, filled with sultana and Corinthian raisins, and, most importantly, it spread the scent of saffron. For its exoticism, the novelty of its taste and texture, Stanislao dubbed the dessert Ali Baba, in reference to One Thousand and One Nights, whose French translation he had read during his stay in the sultan’s prison in Constantinople. | ||||

— Fabrizio Mangoni: I viaggi del Babà, in: Festival della letteratura di viaggio, Roma: Società Geografica Italiana Onlus, 2017, own translation

Original text:

|

How much of all that is true? Should Stanislao really get the credit for inventing the rum baba and does its name really come from a fairy-tale Arab craftsman who robbed the forty thieves of their sesame treasure? As you can see from the quotations above, the first stop on our journey to unravel this mystery is going to be in France.

Babaorum

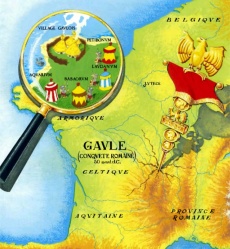

According to one popular publication about the history of France, the rum baba dates back all the way to antiquity. The French term for this dessert, baba au rhum may have come from the name of a Roman military camp called Babaorum. In Julius Caesar’s time, it was one of the four Roman camps surrounding the last independent Gaulish village in Armorica. The other three were called Laudanum, Petibonum and Aquarium.[1]

Yet a different source, Larousse Gastronomique, the Bible of French cuisine, confirms the story of King Stanislas inventing the baba and naming it after a character from an Arabic fairy tale.

| Baba, a cake made from leavened dough that contains raisins and is steeped, after baking, in rum or kirsch [Alsatian cherry liqueur] syrup. […] The origin of this cake is attributed to the greediness of the Polish king Stanislas Leszcsynski [sic], who was exiled in Lorraine. He found the traditional kouglof [Alsatian bundt cake] too dry and improved it by adding rum. As a dedicated reader of the Thousand and One Nights, he is said to have named this creation after his favourite hero, Ali Baba. This recipë was a great success at the court of Nancy [capital of Lorraine], where it was usually served with a sauce of sweet Málaga wine. […] Sthorer [sic], a pastrycook who attended the court of the Polish king, perfected the recipë using a brioche steeped in alcohol; he made it the speciality of his house in the Rue Montorgueil in Paris and called it ‘baba’. |

| — Larousse Gastronomique, ed. Joël Robuchon, Hamlyn, 2009, p. 51 |

As we shall see, Larousse Gastronomique isn’t much more reliable than Astérix as a source of historical knowledge. After all, why would Stanislas take an Alsatian kouglof and steep it in Alsatian kirsch while staying in Lorraine? Was this recipë really developed by the king himself or rather by one of his pastrycooks, such as the aforementioned Stohrer? And most importantly, why would a Pole name a cake after some Arab guy, if the word “baba” had already meant “bundt cake” in his own native language for centuries?

It looks like we need to take a closer look at this King Stanislas and his relation to the baba. You could shoot a few action movies based on his biography, but I will do my best to recap his life and his times as succinctly as possible.

A King-in-Exile

Poland entered the 18th-century as a great power in decline, under King Augustus II of House Wettin, who also ruled the Electorate of Saxony, a relatively small, but rich, state in what is now eastern Germany. Just before the end of the previous century (1698), Augustus was visited by Tsar Peter the Great of Russia, on his way back from his grand survey of Europe. Both monarchs were unusually tall, strong and able to consume copious amounts of alcohol. So when they met, they engaged in a several-day-long bout of binge drinking punctuated with cannon-shooting and bare-handed-horseshoe-breaking contests. And, while they were at it, they also decided to wage war against Sweden. A coalition of Saxon, Russian and Danish forces attacked the mighty Baltic empire soon afterwards (1700). But, like many other drunken ideas, it didn’t go exactly as intended. The Swedes smashed the Danes in Zealand, the Russians at Narva and the Saxons on the Daugava, and then proceeded to invade Poland. Polish senators tried to explain to King Charles XII of Sweden that Augustus was at war with him as Elector of Saxony rather than as King of a neutral Poland, but to no avail. The Swedes soon captured Vilno, Warsaw, Poznań and Cracow (1702), and Charles started looking around to find Poland a new king. His first choice was James Sobieski, the eldest son of the previous king, but Augustus had him imprisoned in Saxony (1704).

Anti-Saxon opposition in Poland sent a delegation to the king of Sweden, headed by the Palatine of Poznań, Stanisław Leszczyński🔊. King Charles was so charmed by the young, handsome, well-read and eloquent palatine, that he decided to make him his own puppet on the Polish throne. The royal election of 1705 – the first in Polish history to be conducted in the presence of foreign troops – was widely considered a farce, but it did dutifully elect the 28-year-old Leszczyński as the dethroned Saxon’s successor. He was crowned (in Warsaw rather than in Cracow, the traditional coronation site) with a crown which Charles had lent him for the ceremony and took back just afterwards. The reign of Stanisław I lasted no longer than four years. The situation changed dramatically when the Russians crushed the Swedish army at Poltava (1709), forcing King Charles into exile in the Ottoman Empire. Augustus got his Polish throne back, while Stanisław ran to the Swedish city of Stettin (now Szczecin, Poland) and thence to the Ottoman Empire, to consult further plans with Charles.

Bender, a town in what is now Transnistria (between Moldova and Ukraine), was where King Charles stayed for a few years after Poltava and the only place in the Ottoman Empire where Stanisław spent any amount of time. He never was in Constantinople, let alone in an Ottoman prison. Eventually (1714), Charles gave him the Swedish-owned Duchy of Two Bridges (now Zweibrücken, Germany), where the former Polish king, inspired by Ottoman architecture, built himself a little palace he called Tschifflik (from Turkish “çiftlik”, or “farm”). Unfortunately, Stanisław had to move out after his Swedish protector passed away (1718), so he moved to a modest palace in nearby Wissembourg. It’s a town in Alsace, a border region which by that point had belonged to France for almost forty years, but was still mostly German-speaking (Alsace would later change hands between Germany and France like a ping pong ball, eventually staying with the latter). Maybe Stanisław would have stayed there for the rest of his life, if not for an unexpected visit by matchmakers from Versailles, who asked him for his daughter’s hand in the name of King Louis XV of France. And so Princess Marie Leszczyńska married Louis, seven years her junior, and proved to be a perfect wife (she would give him ten children without getting much in the way of his many extramarital liaisons), while her parents, who wanted to be closer to their only living daughter, moved into Chambord, one of the most luxurious châteaux of the Loire Valley.

Meanwhile, back in Poland, Augustus II continued to reign until he ended his gluttonous life by dying from gangrene after diabetic foot amputation (1733). Stanisław, counting on his son-in-law’s support, decided it was a good occasion to try and win back the Polish throne. He travelled incognito back to Warsaw, where he made his sudden appearance on the election field and was chosen – legally, this time – as king of Poland. His earlier coronation was retroactively declared valid, so there was no need to repeat it. However, the history from almost thirty years before repeated itself in reverse – foreign troops, Russian this time around, captured Praga, the eastern suburb of Warsaw, where they arranged a rival election of Augustus II’s son, soon afterwards crowned in Cracow as King Augustus III. Stanisław escaped from Warsaw to Danzig (Gdańsk), a city which managed to hold out against a Russian siege for some time. A network of alliances covering Europe transformed the fight for the Polish throne into a major international conflict, which – despite being known as the War of the Polish Succession – was fought out mostly in Italy and on the banks of the Rhine. France was quick to capture Lorraine (another border region), but (except for a small and unsuccessful landing operation in Westerplatte near Danzig) did little to help Stanisław keep his crown. In the end, Danzig fell to the Russians and Stanisław, disguised as a peasant, escaped (once again) to Königsberg (now Kaliningrad, Russia).

The war ended with Augustus III staying on the Polish throne. As a consolation prize, Louis XV gave his dad-in-law the Duchy of Lorraine and Bar (1737), where Leszczyński lived out his years while still being addressed as “king” and where, in the words of Voltaire, he was “able to do more good than all the Sarmatian [that is, Polish] kings ever managed to do on the banks of the Vistula.”[2] Lorrainers still remember Leszczyński as King Stanislas the Good (Stanislas le Bienfaisant), even though he earned this moniker largely due to the “good tsar, bad boyars” principle, finally living his dream of reigning as a charitable enlightened monarch surrounding himself with artists and philosophers, while leaving the day-to-day chores of running the government to his French chancellor, the widely hated Marquis de La Galaizière.

Although Stanislas and the Wettins of Saxony were fierce political rivals, they were united in their love of good food, sweets, wine and women. In Poland, the reign of Augustus III finally brought a period of long-sought peace, now known as the “Saxon Carnival”, when the Polish nobility lived out the proverb:

Under a Saxon king, | ||||

— Polish saying (18th century), own translation

Original text:

|

Meanwhile, Stanislas, in his “little Versailles” at Lunéville, hosted Voltaire, Rousseau and Montesquieu, enjoyed the theatre of automata in his exotic gardens and stuffed his face with fantastic creations sculpted from sugar and ice cream by his court confectioner Joseph Gillers. He got terribly fat, yet still outlived Augustus III; he chose not to fight for the Polish throne again, though, leaving Empress Catherine the Great of Russia to pick his namesake, Stanisław Poniatowski, as Poland’s new (and last) king (1764).

One of the shortest-reigning kings of Poland, but also the longest-lived, died a particularly nasty death. It’s said that he wanted to light his pipe or that he just plunged himself in deep thought next to a fireplace; but pissing into the fireplace wasn’t unusual at all back then, especially for elderly monarchs who didn’t always feel like walking all the way to the outhouse. In any case, his clothes caught fire and the former king died from severe burns after a few days of agony.

TL;DR: Stanisław Leszczyński was a king of Poland, then he was exiled, lived in Alsace for some time, then he became king of Poland and got exiled all again, and spent the rest of his life as duke of Lorraine and a great gourmet. But so far, we haven’t learned anything new about the baba.

Baba, baby

The Polish word “baba” is unusually rich in meanings. In its original Proto-Slavic sense, it refers to a grandmother or, by extension, any elderly lady. In old Polish, the same word was used for any peasant woman and is still used to describe an uncouth, boorish hag. Other meanings include “female street vendor”, “herbalist”, “midwife” and “witch” (as in the most famous Slavic witch, Baba Yaga). A “baba” may even refer to a married or widowed woman of any age, as in “moja baba”, or “my wife”. You can use the diminutive form, “babka”, for a young and attractive woman, much like the “babà” in the Neapolitan dialect of Italian. But don’t overdo it, because if you diminutize the word even further, you’re gonna get a “babcia”, or “granny”.[3]

In Polish grammar, the plural and genitive form of “baba” is “baby”🔊 (pronounced: bah-bih, not bay-bee). You can sometimes see in Poland some half-translated labels, like “żel do mycia baby”, which was probably meant to say “baby-washing gel”, but actually says “crone-washing gel”. When interwar Poland’s top heart-throb Eugeniusz Bodo sang “ach te baby” in the 1930s, he wasn’t addressing his one and only baby; he meant all women in general. Or did he mean the cakes?

Lovely “baby”, oh these “baby”! | ||||

— Jerzy Nel, Ach te baby (1933), own translation

Original text:

|

So which of these multiple meanings gave rise to “baba”, the bundt cake? Did the cake use to resemble a pagan stone idol, which is also called “baba” in Polish? Or does the cake’s name come from its resemblance to a peasant woman’s long pleated skirt? Or perhaps it comes from the fact that it’s always been old women who were most experienced in the tricky art of yeast-cake baking?

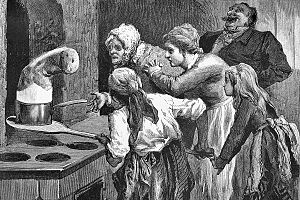

After all, baking a beautiful, tall, airy baba was one of the most demanding tasks Polish home cooks ever had to face. Great care was needed to prevent the cake from sinking or browning a little too much. A housewife who aimed for the perfect baba had to start by choosing the best ingredients – high-quality wheat flour, good beer yeast and fresh butter. The oven had to be heated as much as possible, so that it could keep a constant temperature for a long time. The moulds had to be perfectly clean before being filled with dough and popped into the oven. Then came the almost magical practices whose goal was to prevent the baba from “catching a cold” and falling. Doors and windows were sealed to avoid draughts, women walked on their toes and talked in whispers when close to the oven, and finally, the baba was gently placed on down pillows for cooling. And, of course, no men were allowed in the kitchen; the baking of a baba was a baby-only affair.[4]

In any case, the word “baba” was used in the sense of “bundt cake” at least as early as the 17th century,[5] so it’s hard to guess why Stanislas would have had to reinvent the word from Ali Baba.

From Stohrer to Savarin

While the word “baba” is without a doubt of Slavic origin (so there’s never been a need to borrow it from Arabic), there is no reason to believe that a turban-shaped yeast cake is a native Polish, or generally Slavic, invention. The same kind of cake has been known, under various names, throughout central Europe, from the Netherlands, to Alsace, Germany, Switzerland, Austria, the Czech lands, Poland, to Russia. In German-speaking territories it’s known as “Gugelhupf” or “Kugelhupf”. The Kugelhupf didn’t always have to be sweet, as evidenced by the tradition of former eastern Poland, where they still bake a potato casserole with onions and bacon (the Jews make it too, but without the bacon) and call it “potato babka”, “kugel”, “kugiel” or “kugelis”.

The origin of this German name is even more mysterious than that of the Polish “baba”. “Kugel” means “a ball” in modern German, but the cake was never baked in such a shape. Perhaps “Gugel” comes from Latin “cucullus”, or “a hood”, while “Hupf” is the equivalent of “hop” (as in jumping)? But what would a jumping hood have to do with a bundt cake? According to a pair of famous German etymologists, brothers Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm (who also collected German folk tales as part of their linguistic studies), a yeast cake would grow so fast that it jumped, but it’s possible that what they recorded was just folk etymology. Or maybe it has something to do with prancing around at weddings, where bundt cakes were often served?

This kind of cake was especially popular in Alsace, particularly on special occasions, such as weddings or the Three Kings Day (Epiphany). The Alsatians have come up with some legends to explain the name of this cake, known as “Kugelhopf” in the local dialect of German. According to one legend, it was invented by an Alsatian priest, whose name was Gérard Kugelhopf.[6] A more interesting legend claims that it was the Three Kings (or Magi) themselves who stopped on their way from the Holy Land to Cologne (where their alleged relics are still held) in the picturesque Alsatian town of Ribeauvillé. There, they stayed in the house of a local baker named Kugel and showed their gratitude by giving him a recipë for a yeast cake, which he would later make in the shape of their turbans.[7]

And so we may finally solve the riddle. During his stay in Alsace (between his two stints as king of Poland), Stanislas employed local chefs, pantlers and pastrycooks. It’s quite likely that from time to time they served him some Alsatian specialities, including the Kugelhopf, and that he couldn’t fail to notice that it’s actually the same thing as the Polish baba. The best-known pastrycook to have begun his career at Stanislas’s court was Nicolas Stohrer (1706 – ca. 1781),[8] whom Princess Marie took with her to Versailles when she became Queen of France. For the young Stohrer this meant the best bullet point on his resumé he could have ever dreamed of, but it also gave him the opportunity to popularize the pastry from his home region at the French royal court. The only problem was the cake’s German name, which the French found unpronounceable and unspellable; if the French absolutely have to write that word down, they come up with at least as many different ways to spell it (cougloff, goglopf, gouglouff, guglhupf, kougelhopf, kouglhupf, kouglof, etc.) as they have ways to spell Leszczyński’s surname. So instead of calling the cake by its German name, Stohrer presented it to the French as baba, the name he had learned from his Polish employer.[9] The new word started to crop up in French texts half a century later, including in a letter from Denis Diderot, a co-author of the Encyclopédie, to his lover, in which he described the banquets held by the Baron d’Holbach in his Grand-Val castle in southern France (quite far away from Alsace, Lorraine and Versailles):

| I’m going to pass another week here. Pray to God that I don’t die from indigestion. Every day, they bring us from Champigny the most furious and most perfidious eels, and then little watermelons from Astrakhan, and then sauerkraut, and then partridges with cabbage, and then young partridges à la crapaudine, and then babas, and then pies, and then tarts, and then you would need twelve stomachs [to eat all that…] Fortunately, we drink in proportion, so it all goes well. | ||||

— Denis Diderot: Lettres à Sophie Volland, CVI: Au Grandval, le 24 septembre 1767, in: Œuvres complètes, ed. J. Assézat, Maurice Tourneux, vol. 29, Paris: Garnier, 1876, p. 246, own translation

Original text:

|

Somehow, along the way, “baba” has lost its original feminine gender and its association with women, becoming a masculine noun in both French (“le baba”) and, later, Italian (“il babà”), which may explain how the Ali Baba connection may have seemed plausible to non-Slavs.

In 1730, Stohrer decided to start his own business, so he opened – next to the northern coach terminus in Paris, at Mont Orgueilleux (now 51, Montorgueil Street) – the oldest Parisian pastry shop still in operation. Did he sell babas / kouglofs there? Most probably. Were they imbibed with rum? Probably not, at least not from the start. 18th-century sources are quite unanimous in describing the baba as coloured with saffron and studded with raisins, without any mention of rum. At the beginning of the 19th century, the great gourmet Grimod de La Reynière would already attribute the baba to Stanislas, but it still wasn’t the rum baba.

From a collection of pastry recipës published in the 1930s by a Dr. Oetker factory in Oliva, Free City of Danzig (now part of Gdańsk, Poland)

| The baba is a Polish dish invented by Stanislas Leczinski [sic], King of Poland and Grand [sic] Duke of Lorraine and Bar, a great gourmet towards the end of his days, who was no stranger at all to culinary practice. Saffron and Corinthian raisins are the principal seasonings of the baba, but few cooks know how to make it well. | ||||

— Alexandre-Balthazar-Laurent Grimod de La Reynière: Manuel des amphytrions, Paris: Capelle et Renard, 1808, p. 170, own translation

Original text:

|

In pre-revolutionary France, rum was rare anyway, mostly due to high custom duties, imposed to protect the producers of domestic brandies and other alcohols. It was only at the beginning of the 19th century that the French learned to appreciate the English punch, which was made from Caribbean sugar-cane rum. In the 1840s, rum started to appear in French dessert recipës. And so the tasty legend of a Polish king who soaked a dry kouglof in rum and named it after a fairy-tale protagonist, falls apart like a house of cards. Mr. Michael Krondl, a food historian, has put it best:

| The French love to tell anecdotes about their food, and if some eminent person can be attached to a dish, so much the better. Some of the tales happen to be true, many are made up, but in some cases the stories are like a napoleon or millefeuille made up of layers of crisp fact and frothy fiction. Pulling it apart neatly is almost impossible. What’s more, once you’ve scraped away all the fluff, the truth you are left with can be a little dry. |

| — Michael Krondl: Sweet Invention: A History of Dessert, Chicago Review Press, 2011, p. 171 |

Soaking individual helpings of dry cake in wine, coffee or chocolate is surely an old practice, but it’s not the same as soaking an entire bundt cake prior to serving. Whose idea was it then? We don’t know. We do know, however, that in 1845 Auguste Julien, a co-owner of a pastry shop at Place de la Bourse in Paris, expanded his offer by introducing small babas with candied orange zest instead of raisins and imbibed with rum (or kirsch)-based syrup. And because, as we already know, the French prefer those dishes that they can associate with celebrities, he named this new kind of baba “savarin”[10] – after the famous gourmet Jean-Anthelme Brillat, who changed his name to Savarin (or was it his father?), so that he could inherit his aunt’s property.[11]

As for the distinctive shape of the baba or Gugelhupf, sometimes also known the “Turk’s head”, such moulds were already used by the Romans ca. 200 CE.[12] Which means that history came full circle, from ancient Rome, via Germany, Poland, Alsace, France and back to Italy and the Neapolitan babà al rum.

Recipë

History also came full circle when recipës for Polish baby came back to Poland, but “improved” by the addition of alcohol-laced syrup. Here’s one, with arak-based punch, rather than rum, added to the dough before baking:

| Ordinary punch: Soak one pound of sugar in water, but first use it to scrape the zest of six lemons, put it immediately into a pot and boil into syrup; pour a quart of arak and then the juice squeezed from the six lemons into the syrup; keep under cover for some time, then pour the [punch] essence into a bottle […]

Punch babas: Mix two pounds of fine flour with a quart of lukewarm milk and 4 tablespoons of thick yeast, add 10 whole eggs and a quarter of a pound of sugar; leave in a warm place for the night; in the morning, add a pound of lukewarm pre-melted butter and half a quart of punch essence. Knead the dough thoroughly, baste small moulds with fresh butter, half-fill them with the dough; after the dough has risen, put them into a medium-heated oven for three quarters. Remove from moulds while hot. | ||||

— Bronisława L[eśniew]ska: Kucharz polski jaki być powinien: książka podręczna dla ekonomiczno-troskliwych gospodyń, Warszawa: S.H. Merzbach, 1856, p. 368, 424, own translation

Original text:

|

References

- ↑ René Goscinny, Albert Uderzo: Astérix : Le Combat des chefs, Paris: Hachette, 2013, p. 3

- ↑ Voltaire: Candide, or Optimism, trans. Robert M. Adams, ed. Nicholas Cronk, W.W. Norton & Company, 2016

- ↑ Baba, in: Wielki Słownik Języka Polskiego, ed. Piotr Żmigrodzki, Instytut Języka Polskiego PAN

- ↑ Maja Łozińska, Jan Łoziński: Historia polskiego smaku: Kuchnia, stół, obyczaje, Warszawa: Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN, 2012, p. 173–174

- ↑ Baba, in: Elektroniczny słownik języka polskiego XVII i XVIII wieku, ed. Włodzimierz Gruszczyński, Warszawa: Instytut Języka Polskiego PAN

- ↑ Michael Krondl: Sweet Invention: A History of Dessert, Chicago Review Press, 2011, p. 173

- ↑ Kugelhopf, in: Annie Perrier-Robert: Dictionnaire de la gourmandise, Paris: Robert Laffont, 2012

- ↑ Elizabeth Field: Stohrer, Nicolas, in: Darra Goldstein: The Oxford Companion to Sugar and Sweets, Oxford University Press, 2015, p. 657

- ↑ M. Krondl, op. cit., s. 171

- ↑ M. Krondl, op. cit., p. 172

- ↑ Larousse Gastronomique, ed. Joël Robuchon, 1997, p. 141

- ↑ Melitta Weiss Adamson: Food in Medieval Times, Greenwood Press, 2004, p. 69

| ◀️ Previous | 📜 List of posts | Next ▶️ |

| ⏮️ First | 🎲 Random post | Latest ⏭️ |

- Arak

- Baba

- Kirsch

- Millefeuille

- Limoncello

- Punch

- Rum

- Savarin

- Augustus II

- Augustus III

- Jean-Anthelme Brillat-Savarin

- Denis Diderot

- Joseph Gillers

- Alexandre-Balthazar-Laurent Grimod de La Reynière

- Stanisław Leszczyński

- Marie Leszczyńska

- Bronisława Leśniewska

- Louis XV

- Peter the Great

- Nicolas Stohrer

- Vladislaus IV Vasa

- Voltaire

- Naples

- Paris

- Alsatians

- Ancient Romans

- Antiquity

- Early Modern Period

- Recipës

- Warsaw

- Cracow

- Szczecin

- Italy

- Turkey (country)

- Russia

- Germany