Difference between revisions of "Even Older Polish Cookery for Complete Beginners"

| Line 182: | Line 182: | ||

You could explain these doubts away by saying that the more popular a book is, the more likely it is to be worn down to nothing. It’s even more true for a cookery book, which was particularly vulnerable due to its utilitarian character. As for the question of its exact title, one can imagine a scenario in which different printers published the same book under different titles, which wasn’t that rare a case at all. Be it as it may, some question marks remained. | You could explain these doubts away by saying that the more popular a book is, the more likely it is to be worn down to nothing. It’s even more true for a cookery book, which was particularly vulnerable due to its utilitarian character. As for the question of its exact title, one can imagine a scenario in which different printers published the same book under different titles, which wasn’t that rare a case at all. Be it as it may, some question marks remained. | ||

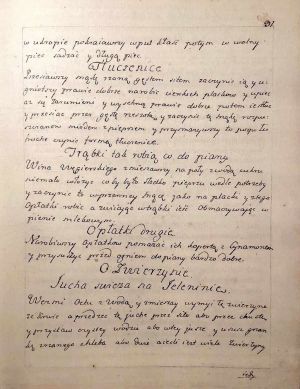

| − | [[File:O zwierzynie.jpg|thumb|A folio of the manuscript ''Zbiór dla kuchmistrza'' (''A Collection for the Master Chef''). The heading ''O zwierzynie'' (''Of Game Dishes'') opens the block of recipës copied from ''Kuchmistrzostwo''.]] | + | [[File:O zwierzynie.jpg|thumb|A folio of the manuscript ''Zbiór dla kuchmistrza'' (''A Collection for the Master Chef''). The heading ''O zwierzynie'' (''Of Game Dishes'') opens the block of recipës copied from ''Kuchmistrzostwo''.]] |

The discovery which practically removed all the remaining doubts about the actual existence of ''Kuchmistrzostwo'' and its contents was made about ten years ago by Dr Svitlana Bulatova{{czyt|Switłana Bułatowa}} at the Manuscript Institute of the National Library of Ukraine in Kyiv.<ref>{{Cyt | The discovery which practically removed all the remaining doubts about the actual existence of ''Kuchmistrzostwo'' and its contents was made about ten years ago by Dr Svitlana Bulatova{{czyt|Switłana Bułatowa}} at the Manuscript Institute of the National Library of Ukraine in Kyiv.<ref>{{Cyt | ||

| tytuł = Рукописна та книжкова спадщина України | | tytuł = Рукописна та книжкова спадщина України | ||

Latest revision as of 13:25, 6 December 2024

I once wrote here about old Polish recipës that were both extremely easy to cook and surprisingly familiar to our own times, which made them perfect for people who were only starting to try their hand at historical culinary reënactment. We could see how a recipë’s simplicity could also mean its durability; scrambled eggs, for example, are still prepared in much the same way as they were two hundred, four hundred or one thousand years ago.

I took the recipës from Compendium Ferculorum (A Collection of Dishes) by Stanisław Czerniecki,🔊 first published in 1682. I wrote then that it was the oldest cookbook ever printed in Polish. Well, that’s no longer true. Polish and Ukrainian historians have recently confirmed that an even older Polish-language cookery book was published a century and a half before Compendium Ferculorum. Not a single volume of that older book has survived to our times, but now we know for sure that it did exist. Some clues about its possible existence in the past had been know earlier, but as the surviving fragments could be suspected of being some 19th-century hoaxes, there was no certainty. Until now. So let’s follow the fascinating history of this new oldest Polish printed cookbook and how it was rediscovered. And then, let’s pick a recipë out of it to try out – one for beginners, of course.

Cookery Bookery

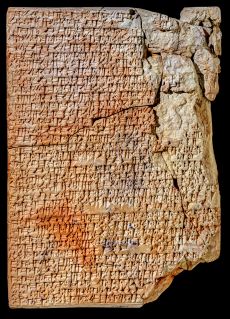

Cookbooks are one of the oldest literary genres in the world. The earliest known culinary recipës were written down in cuneiform script on clay tablets, in Babylonia, around the 19th century BCE.[1] And even these were most likely copied from even older tablets, now lost to time. Because the thing with recipës is that they’re much more likely to be copied than written from scratch. You can even see it in the Polish word for “recipë”, “przepis”,🔊 which literally means “something that is rewritten”. Oftentimes, the copyist would add something to the recipë, or perhaps makes some abridgements, redactions or modifications – thus allowing the recipë to evolve. In pre-Internet times, culinary recipës were probably some of the best examples of memes, or units of cultural evolution.[2]

For this reason, when it comes to old cookbooks, it’s difficult to even speak of authorship in any meaningful way. Even if you can see somebody’s name on the title page, you can’t be really sure whether it’s the name of the original author or perhaps of a translator, editor, copyist or publisher. Or maybe of someone who was a little bit of all the above. For the sake of simplicity, I will refer to such a person as “the author”, but keep in mind that they need not necessarily be the actual content creator as understood by modern copyright laws. Besides, even the idea of copyright didn’t exist before the 19th century. Before that, people would just go and rewrite or reprint books (culinary or any other) without asking anyone for permission. They would sometimes indicate the original author’s name in the copy, but sometimes not. The very idea of authenticity didn’t exist either, so a copy wasn’t seen as something inferior, but rather as a new, maybe even better version of the original thing. According to Galen of Pergamon (of whom I wrote before), the famous Library of Alexandria was able to grow so big thanks to a policy of sending royal customs officers to each ship which called at the local port, in order to gather any scroll of papyrus or parchment they could find and take it for scribes to make copies of. Then, they would give the shining new copies to the ship’s captain, while the library would contend itself with the timeworn originals.[3] And that was considered progress, not intellectual property theft!

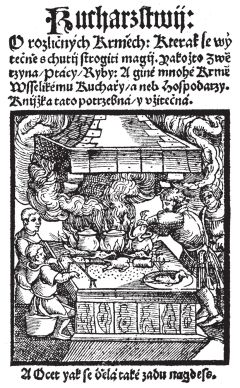

Naturally, copying books by hand was labour-intensive and, therefore, costly (even despite relatively low labour costs in the past). Besides, few people could read anyway, so cookbooks (just like any books for that matter) were a rare luxury. This began to change once Johannes Gutenberg🔊 invented the movable-type printing press. He used his invention to publish the first printed book (a Bible, obviously) in 1455. It was only 15 years later in Rome that the first ever cookbook was published in print. It was De honesta voluptate et valetudine (Of Honest Pleasure and Good Health) by Bartolomeo Sacchi🔊 (1421–1481), better known as Platina, who served as a papal secretary and librarian. In fact, Platina copied most of the recipës from Martin do Como’s handwritten Libro de arte coquinaria (Book of Culinary Arts). It took another 15 years for the first cookbook printed in a vernacular language to come out, namely the German Küchenmeisterei🔊 published by Peter Wagner.🔊 The 15th century also saw the first printed cookbooks in French, Italian and English, and the first half of the 16th century, in Dutch, Catalan, Spanish and Czech. The latter book, entitled Kuchařstvi🔊 and published by Pavel Severýn🔊 in 1535, in Prague, was a translation of the aforementioned German text. Both titles can be translated as Cooking Mastery.

And how long did one have to wait for the first cookbook printed in Polish?

A Groundbreaking Discovery

The way historians often make their most interesting discoveries is by dismantling the covers of old books. This is because bookbinders in the past frequently strengthened the covers by gluing together pages torn from even older tomes. Luckily for us, the very first cookbook printed in Polish was among the many books to have fallen victim to this kind of recycling.

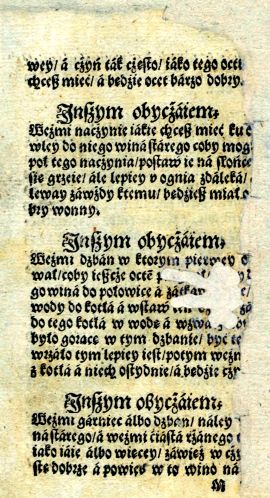

In 1891, Zygmunt Wolski🔊 (1862–1931), an apprentice librarian at the Krasiński Library in Warsaw, walked into Cezary Wilanowski’s🔊 (1846–1893) second-hand bookshop, where he found a folder containing four loose sheets of paper that had been removed from an old book cover. The cover bore no title, but it did bear the year of publication: 1538. The four sheets which were reused to strengthen the cover came from three different printed books. Two of the sheets were covered with culinary recipës – all for different kinds of vinegar, as it happened. Wolski carefully examined the watermarks on the paper, the typeface and the language used in the recipës, and concluded that they must have been printed in the first half of the 16th century.[4]

Wolski found the sheets only a year after Artur Benis🔊 (1865–1932), a historian at the Jagiellonian University in Cracow who was busy researching the history of book printing in Poland, had published his work on inventories of Cracow’s mid-16th-century print shops. Back in the 16th century, Cracow was Poland's capital city and the cradle of the nation's printing business. The inventories studied by Benis were typically made for the purposes of inheritance proceedings and contained lists of books which a print shop owner had printed, but died before he could sell them. And so, in an inventory made in 1555, after the death of Helena Unglerowa,🔊 the widow of Florian Ungler🔊 (d. 1536), who had been the first person to print books entirely in Polish, there was a mention of 100 unbound copies of a book whose rather unpronounceable title (to anyone who isn’t Polish) was Kuchmistrzosthwo🔊 (Cooking Mastery).[5] Wolski connected the dots and concluded that the two damaged sheets printed with vinegar recipës that he found may have come from an otherwise lost cookbook with such a previously unknown title.

But that’s not all. The same year 1891 saw the publication of two further works which shed more light on these two sheets. Firstly, Benis published the second volume of his Inventories, which contained a mention of a single copy of a cookbook owned by Helena Gałczyna🔊 (d. 1549), the widow of another Cracow printer, Maciej Szarffenberg🔊 (d. 1547). Additionally, four copies of the same book were listed in the inventory of a Szymon Tyrlikowski’s book collection. The title indicated in both inventories, however, was written as Kucharstvo or Kucharsthvo🔊 (Cookery).[6]

Secondly, Čeněk Zíbrt🔊 (1864–1932), a historian at Charles University in Prague, published a reprint of the earliest cookbook printed in the Czech language, that is, the aforementioned Kuchařství.[7] This allowed Władysław Wisłocki🔊 (1841–1900), custodian of the Jagiellonian University Library, to compare the vinegar recipës discovered by Wolski with recipës found in the Czech book. And he realized that what Wolski found were indeed fragments of the oldest printed Polish-language cookbook, but it hadn't been written originally in that language; it was a Polish translation of the Czech Kuchařství. And, according to Wisłocki, the title was rendered into Polish as Kucharstwo, rather than Kuchmistrzostwo as Wolski had claimed.[8] The question of the book’s title has never been fully resolved either way, but somehow, contrary to Wisłocki’s view, it is now more commonly referred to by the longer title.

All this is well and good, but what kind of discovery is it when all that we have from the oldest Polish cookbook are recipës for vinegar? Yes, vinegar was formerly an extremely important preservative and a popular condiment, produced in many different ways, from wine or beer, and sometimes flavoured with various additives. You could, for example, make it like this:

| Take the vessel you wish to use for your vinegar, pour enough old wine to fill half of the vessel, place it in the sunshine and let it stay warm, but better keep it a distance away from fire; this way you will always have good wine vinegar. | ||||||||||

— [Kuchmistrzostwo], [Cracow]: [Hieronim Wietor], [ok. 1540], f1r, Warsaw Public Library, XVI.O.140, own translation

Polish text:

Czech text:

|

Yet still, one would wish for something more than just that.

Another Groundbreaking Discovery

For something more, one had to wait almost forty years, but I believe it was worth it. It was then that Kazimierz Piekarski🔊 (1893–1944), head of the Old Prints Department at the Jagiellonian Library, discovered a badly damaged sheet of paper printed with more recipës from Kuchmistrzostwo (or Kucharstwo, if you wish). He removed the sheet, naturally, from the cover of a different tome, namely the 1549 edition of the Latin-language De Tuenda Valetudine Libri Sex (Six Books on the Preservation of Health) by the aforementioned Galen.

Piekarski examined the typefaces used both on the sheet he had found and on the pages with vinegar recipës discovered by Wolski, and then compared them with the typefaces known to be used by different Cracow printers in the first half of the 16th century. And he came to the conclusion that the two fragments came from two different editions of the same cookbook. The sheet found at the Jagiellonian Library was printed with types used at Maciej Szarffenberg’s print shop, while the two sheets discovered in Warsaw must have been printed with types employed by Hieronim Wietor🔊 (ca. 1480–1547) – rather than by Florian Ungler as Wolski had assumed. But if a hundred unsold copies were found in Mrs. Unlger’s inventory, then Ungler must have also printed his own edition of the same cookbook, although not a single copy of that edition has survived to our times.[9] And this would mean that the first cookbook printed in Polish had at least three different editions from three different printers.

But, perhaps more importantly, on this newly discovered sheet we can finally find recipës not for vinegar, but for decent meat dishes. Even game meat, to boot! In the title of the first recipë we can also see a small, but interesting modification made by the 16th-century Polish translator. The original Czech version speaks of “buffalo, bison or other uncommon game, not found in our lands”, whereas the Polish translation has “buffalo, bison or other game, uncommon in Polish lands” (the buffalo here is the water buffalo, not the American cousin of the European bison). On the one hand, I understand the translator’s urge to localize the text a little, but on the other, it seems to me that he did it somewhat half-heartedly. It’s true that, by the 16th century, bison had already been extinct in Bohemia, or what is now the Czech Republic, but it still roamed the vast forests of Poland, so it wasn’t that exotic to Polish cuisine.

| Buffalo, bison or other game, unusual in Polish lands, but only in foreign countries. Make sauce for this [meat] in the following way. Take raisins, figs and make a toast of white bread, put it all in a mortar and let grind, and once it’s well ground, pour in some heated wine and strain it through cloth, and having cut up the meat into morsels, cover them with the sauce in a cauldron or a pot, season with pepper, ginger, saffron, cloves and sweeten a little with sugar or honey, and add some fried apples, raisins large and small, almonds and anything else, according to [what you have in] your household. | ||||||||||

— [Kuchmistrzostwo], [Kraków]: [Maciej Szarffenberg], [ok. 1540], f1v, Jagiellonian Library, Old Prints Department, Cim 0.913, own translation

Polish text:

Czech text:

|

And then, there remains the question of how to date this oldest Polish cookbook. Its first edition couldn’t be published earlier than 1535, which was when Kuchařství came out in Prague. After all, the translation can’t be older that the original. The latest possible date, on the other hand, is 1547, which is when the cookbook was noted in Szarffenberg’s inventory. It was only in the 21st century that it was possible to significantly narrow this 12-year gap, thanks to a catalogue of the library which belonged to Austrian book collector Hieronymus Beck von Leopoldsdorf🔊 (1525–1596). One of the items listed in his catalogue is “Kuchmistrzstwo Prossowol 1536”. It’s unclear what “Prossowol” could mean; it may have referred to some printer who hailed from the village of Proszowice🔊 near Cracow. In any case, if that printer had published an edition of Kuchmistrzostwo as early as 1536, then it would mean that the Polish translation came out only a year after the Czech original.[10]

An Even More Groundbreaking Discovery

Some historians had their doubts, though. If the cookbook was so popular that it had three or even four editions published within fifteen years, then how come not a single more or less complete copy has survived to our times? Why is it that the only proofs for the book’s existence in the past are just three frayed sheets and a few mentions in inventories, which don’t even agree about its title? Even worse, the two sheets with vinegar recipës got somehow misplaced, so for a time, all that historians had at their disposal was a facsimilë which Wolski had had made and whose authenticity could be questioned.

You could explain these doubts away by saying that the more popular a book is, the more likely it is to be worn down to nothing. It’s even more true for a cookery book, which was particularly vulnerable due to its utilitarian character. As for the question of its exact title, one can imagine a scenario in which different printers published the same book under different titles, which wasn’t that rare a case at all. Be it as it may, some question marks remained.

The discovery which practically removed all the remaining doubts about the actual existence of Kuchmistrzostwo and its contents was made about ten years ago by Dr Svitlana Bulatova🔊 at the Manuscript Institute of the National Library of Ukraine in Kyiv.[11] But hold on, you may say, why the Manuscript Institute? We’re talking about a printed book, aren’t we? Well, yes, but keep in mind what we said about culinary recipës being constantly copied and rewritten. Back when nobody kept a smartphone equipped with a camera and an OCR function in the pocket – back when even photocopiers didn’t exist – people commonly copied recipës they found in printed sources by hand. Sometimes they would even create entire manuscript cookbooks that were compilations of recipës taken from diverse sources, both printed and handwritten. It was one such manuscript, entitled Zbiór dla kuchmistrza, tak potraw jako ciast robienia🔊 (A Collection for the Master Chef, of Recipës for Dishes, as Well as for Cakes) that caught Dr. Bulatova’s attention and led her to get in touch with the foremost specialist on the history of Polish cuisine, Prof. Jarosław Dumanowski🔊 at Copernicus University in Toruń.

The manuscript contains a total of about a thousand recipës, as well as medical, veterinary and gardening tips – all written by the same hand. The sources these recipës and tips were gleaned from are not always indicated in the text, but you can see from the different styles and grammars that they must have originated in various historical periods – mostly within the 16th and 17th centuries. And yet, the copyist who made the manuscript clearly indicated on the title page that he finished his work on 25 July 1757 (such dating is further borne out by water marks found on the paper). Which means that by the time the manuscript was created, the recipës which were copied into it had already been quite old. The copyist himself didn’t sign his work, but the book’s first owner left her signatures on three different pages. It was Rozalia Pociejowa née Zahorowska🔊 (ca. 1690–1762), a prominent noblewoman from the region of Volynia in what is now western Ukraine. What led her to commission such a compilation of recipës from previous centuries? Did she wish to study culinary history? Or maybe these old recipës still seemed relevant to her own times and she saw the collection in purely practical terms? We don’t really know.

What we do know is where a block of 224 recipës which stand out from the rest as being written in a particularly archaic language come from. They are all old Polish translations of recipës from the Czech Kuchařství. It’s clear from the style and the grammar of these recipës that they were all written in early-16th-century Polish, which means that the translation couldn’t have been made at the same time as the manuscript was written. The copyist must have used an existing 200-year-old translation, which was either still preserved in its printed form at the time or had already been copied by hand from a printed book before.

There are other clues, too, which confirm that the author of the manuscript had access to the same printed cookbook of which only the three sheets survive today. One is that the manuscript contains the modified title of one of the recipës that we already saw on the sheet found at the Jagiellonian Library: “buffalo, bison or other game which is uncommon in Polish lands, but only in foreign countries”. Another is a word incorrectly written with the letter T where one would expect the letter K. It looks like the 18th-century copyist had trouble reading 16th-century typeface, in which the K’s and the T’s do indeed look quite similar. See for yourselves: can your make out the word written in the picture below?[12] So if the copyist misspelled a word because he'd misread a printed letter, then he must have been copying a printed text – and this means that the printed text must have existed in the first place!

To sum up: not a single printed copy of the first cookbook printed in the Polish language has survived, but thanks to old print shop inventories, three surviving sheets and one complete manuscript copy, we do know that it existed. We also know that it was first published around 1536 in Cracow, that its title was either Kuchmistrzostwo (Cooking Mastery) or Kucharstwo (Cookery) and that it was a translation of the Czech Kuchařství, which had been published a year earlier and which was itself a translation of the German Küchenmeisterei.

And this, in turn, means that Compendium Ferculorum is not the earliest cookbook to be printed in the Polish language. But it’s still correct to say that it’s the oldest surviving printed Polish cookbook. And it’s also the first printed cookbook that was written originally in Polish rather than translated.

Let’s Cook!

Okay, so what interesting recipës can you find in that oldest Polish cookbook? The recipës are divided into three chapters, or actually even four, except that the fourth chapter isn’t visibly separated from the third.

The first chapter contains recipës for meat dishes. Many of these are for chicken and other birds (e.g., “birds seasoned with onions and encased in dough”), but there are also several recipës for beef (“roasted beef in the Hungarian style”), pork, hare (“hare with or without onions”), as well as various kinds of game, including: partridges, roe deer and red deer venison, wild boar, “buffalo or bison”, and even… squirrels. This is how you can cook the latter:

| Skin them and wash them clean inside, and cook them in meat broth, not too salty, and once they are cooked, make yellow or black sauce for them. To make the yellow sauce: roast squirrel livers and make two or three rye-bread toasts, grind them all up in a mortar, dissolve in meat broth and strain. Place the squirrels in the sauce and season with pepper, ginger, mace, then fry up some apples as you would for any other game, serve in a bowl and remember to salt.

And to make the black sauce: take prunes or fried sweet cherries, make toasts of white bread, place them all in a mixture of vinegar and water, and bring to boil, then strain clean through cloth, add the squirrels, bring to boil, season with pepper, ginger, cloves, and sprinkle some saffron on top. | ||||||||||

— Zbiór dla kuchmistrza tak potraw jako i ciast robienia wypisany roku 1757 dnia 24 lipca, ed. Jarosław Dumanowski, Switłana Bułatowa, Warszawa: Muzeum Pałacu Króla Jana III w Wilanowie, 2021, p. 141, own translation

Original text:

Czech text:

|

Both recipës for squirrels – in their Czech-language version – were tried out by a group of Czechs: food writer Roman Vaněk🔊 and chef Pavel Mencl,🔊 with the help of historian Martin Franc,🔊 in an episode of the Czech-language TV show Zmlsané dějiny🔊 (Hungry for History). Obtaining the principal raw material proved to be difficult as red squirrels, which are native to Europe, are protected by law. They ended up importing some grey squirrels from Britain, where they are trapped and killed as an invasive species. The culinary reënactors were quite satisfied with the end result, except that the colours weren’t as bright as they had expected: rather than yellow and black, the sauces came out in different shades of brown. But this only shows that colours were perceived differently by people back when no artificial food colouring was available.

Oh, but we wanted a recipë for beginners, so let’s keep on looking.

The next chapter is devoted to fish dishes, that is, something to eat during Catholic fasting days, such as Friday. Here you will find many recipës for carp, pike, stockfish (dried cod), as well as salmon, eel, weatherfish, lampreys and crayfish. A large portion of the chapter covers various kinds of aspic dishes. One particularly elaborate recipë is for carp in kisielica,🔊 or a kind of jelly made from fermented rye flour and divided into four parts, each in a different colour: black (with blood), brown (with cinnamon), green (with parsley) or white (with cream).

The recipës for buffalo or bison (with beef substituted for the game), as well as for various kinds of kisielica, were tried out by Maciej Nowicki, chef at the Wilanów Royal Palace in Warsaw, aided by Prof. Dumanowski, in the fourth episode of the Polish-language TV show Historia kuchni polskiej🔊 (History of Polish Cuisine), which was all about the oldest Polish cookbook. But these recipës, too, are definitely for more advanced cooks.

The third chapter has recipës for “Saturday food”, which means food allowed by the Catholic Church on the milder fasting days, such as Saturday. The milder version of fasting still excluded the meat of land-dwelling animals, but allowed the consumption of dairy and eggs. This chapter abounds in recipës for various kinds of dumplings, porridges and yolk-thickened soups. At the very end, in an implicit fourth chapter, we can find the vinegar recipës, some of which we already know from the two surviving sheets. But let’s stick to the porridges. The Polish word for “porridge”, “kasza”,🔊 had a broader meaning in the past than it has today and referred not only to boiled cereal grains, but to any kind of food with porridge-like consistency. For example, you could chop some apples into small chunks, fry them up and then pass through a sieve to obtain what was referred to as “apple porridge”.

One recipë that caught my attention is for “rice porridge”.

| To make rice porridge: take as much rice as you want and some clean cream, cook it first and then rinse the rice, and place it in the cream, add some butter and mix, so it doesn’t burn and you have clean porridge, and then, when you serve it in a bowl, sprinkle with cinnamon and sugar. | ||||||||||

— Zbiór dla kuchmistrza tak potraw jako i ciast robienia wypisany roku 1757 dnia 24 lipca, ed. Jarosław Dumanowski, Switłana Bułatowa, Warszawa: Muzeum Pałacu Króla Jana III w Wilanowie, 2021, p. 168, own translation

Polish text:

Czech text:

|

I suppose that to any Polish person this dish would immediately bring back some childhood memories. Rice with cream, sugar and cinnamon was a typical children’s food when I was growing up. The only difference between modern and historical versions is that in our times, you would cook the rice in milk and only then mix it with cream, rather than cook the rice already in the cream. A more important distinction is in the way this dish was and is perceived. In our times, it would be seen as a rather simple dish, tinged perhaps with a bit of nostalgia for some people. But in the 16th century, it would have been the pinnacle of luxury. Rice, sugar and cinnamon were all considered exotic spices that were imported from overseas for a lot of money. Butter and cream were sourced locally, but they were the most expensive of all dairy products. What’s more, in a cuisine where colours played an especially important role, white was prized above all other colours – hence the warning not to burn the rice. All in all, it was definitely a rich man’s porridge.

For my reconstruction, I used 30%-fat cream, which I diluted a little with milk. I added cane sugar (beet sugar was unknown in the 16th century) already while cooking, to let it dissolve well in the cream. At the end, I only had to sprinkle the porridge with powdered cinnamon – and that’s it! I did like the flavour – it tasted just the way I expected rice with cream, sugar and cinnamon to taste.

If you can read Polish and would like to try out some other recipës form the oldest cookbook in that language, then I’ve got some good news: the entire manuscript, edited by Bulatova and Dumanowski, was published in 2011 by Wilanów Palace Museum in Warsaw. This way, almost half a millennium after the first publication of Kuchmistrzostwo, its recipës were published in print once again.

Timeline of Early Printed Cookbooks

And to summarize what I wrote above, here’s a little table to show you the sequence in which the first cookbooks printed in given languages were originally published (up to the middle of the 16th century) – in relation to selected events from universal history.

| First cookbooks printed in given languages | Decade | Selected events in Europe, for guidance |

|---|---|---|

| 1451–1460 |

• 1453, Contantinople (Istanbul) – Ottoman Turks under Sultan Mehmed II capture the capital city of the eastern Roman Empire | |

|

• Bartolomeo Platina (☛), De honesta voluptate et valetudine, Rome ca. 1470 – in Latin. |

1461–1470 |

• 1461, France – François Villon writes his testament in verse. |

| 1471–1480 |

• 1473, North Sea – amidst the Anglo-Hanseatic War, privateers from Danzig (Gdańsk) loot the Last Judgement triptych (☚) by Hans Memling (now still in Gdańsk). | |

|

• Peter Wagner, Küchenmeisterei, Nuremberg 1485 – in German. |

1481–1490 |

• 1489, Cracow – Veit Stoß finishes his work on St. Mary’s altarpiece, a masterpiece of Gothic sculpture (still in Cracow). |

|

• Richard Pynson, The Boke of Cokery, London 1500 – in English. |

1491–1500 |

• 1492 – Cristoffa Colombo (☚) sails under a Spanish flag in search of a western route to India, ending up in the Caribbean. |

| 1501–1510 |

• 1505, Radom – King Alexander Jagiellon of Poland (☚) signs the Nihil Novi act, establishing parliamentary monarchy in his kingdom. | |

|

• Thomas van der Noot, Een notabel boecxken van cokeryen, Brussels 1514 – in Dutch. |

1511–1520 |

• 1517, Wittenberg – Martin Luther publishes his 95 theses against the sale of indulgencies, kicking off the Protestant Reformation. |

|

• Robert de Nola, Libro de guisados, Toledo 1525 – in Spanish (translated from Catalan). |

1521–1530 |

• 1522, Graudenz (Grudziądz) – Niklas Koppernigk aka Copernicus (☚), Canon of Ermland, makes a speech about monetary policy at the dietine (regional assembly) of Royal Prussia. |

|

• Pavel Severýn, Kuchařství, Prague 1535 – in Czech (translated from German). |

1531–1540 |

• 1534, London – King Henry VIII (☚) becomes the head of the Church of England. |

References

- ↑ Gojko Barjamovic et al.: The Ancient Mesopotamian Tablet as Cookbook, in: Lapham’s Quarterly, 11 June 2019

- ↑ Many people think of memes as nothing but silly pictures shared on the Internet, but they are, in fact, as old as human culture itself. The Internet is only a new medium for memes to spread in, faster than ever before. The notion of memes, as cultural equivalents of genes, was coined by the famous biologist Prof. Richard Dawkins in 1976 (when the Internet was still in its infancy), who wanted to show that you can also study evolution outside of biology (R. Dawkins: Memes: the new replicators, in: The Selfish Gene, Oxford University Press, 1989, p. 189–201). The very idea of a meme would soon become a successful and quickly evolving meme in and of itself.

- ↑ Galen of Pergamon: Commentary on Hippocrates’ Epidemics, in: Andrew Smith: Attalus

- ↑ Zygmunt Wolski: Kuchmistrzostwo: Szczątki druku polskiego z początku w. XVI, Biała Radziwiłłowska: self-published, 1891, p. 11–12

- ↑ Artur Benis: Materyały do historyi drukarstwa i księgarstwa w Polsce, vol. I. Inwentarze księgarń krakowskich Macieja Scharffenberga i Floryana Unglera (1547, 1551), Kraków: Akademia Umiejętności, 1890

- ↑ Artur Benis: Materyały do historyi drukarstwa i księgarstwa w Polsce, vol. II. Inwentarze bibliotek prywatnych (1546–1553), Kraków: Akademia Umiejętności, 1891

- ↑ Kuchařství: O rozličných krmích, kterak se s chutí strojiti mají, ed. Čeněk Zíbrt, Praha: F. Šimáček, 1891

- ↑ Władysław Wisłocki: Przewodnik Bibliograficzny, 14/10, Kraków: self-published, October 1891, p. 166–167

- ↑ Kazimierz Piekarski: Miscellanea Bibljograficzne: „Kuchmistrzostwo” Macieja Szarffenberga, in: Przegląd Bibljoteczny, IV, Kraków: Wydawnictwo Związku Bibljotekarzy Polskich, 1930, p. 415–418

- ↑ Magdalena Herman: Ślady pierwszej polskiej książki kucharskiej, in: Silva Rerum, Warszawa: Muzeum Pałacu Króla Jana III w Wilanowie, 3 December 2020

- ↑ Світланa Олегівнa Булатова: Рукописна книга ХVIII ст. з історії старопольської кухні „Zbiór dla kuchmistrza tak potraw jako ciast robienia” з фондів Інституту рукопису Національної бібліотеки України імені ВІ Вернадського, in: Рукописна та книжкова спадщина України, 20, 2016, p. 22–42

- ↑ The correct answer is: “kotła”.🔊

Bibliografia

- [Kuchmistrzostwo], Cracow: ca. 1540

- surviving fragment (recipës for vinegar), Warsaw Public Library, ID number: XVI.O.140

- surviving fragment (recipës for meat dishes), Jagiellonian Library, Old Prints Department, ID number: Cim 0.913

- Artur Benis: Materyały do historyi drukarstwa i księgarstwa w Polsce, Kraków: Akademia Umiejętności

- Aleksander Brückner: Źródła do dziejów literatury i oświaty polskiej: VII. O pismach dziś nieznanych: IV. Rozmaitości, in: Biblioteka Warszawska, t. I, Warszawa: 1895, p. 24–28

- Switłana Bułatowa, Jarosław Dumanowski: „Kuchmistrzostwo”: Kopia tekstu najstarszej polskiej książki kucharskiej z XVI wieku, in: Silva Rerum, Warszawa: Muzeum Pałacu Króla Jana III w Wilanowie, 18 lipca 2022

- Jarosław Dumanowski: Tajemnica pierwszej polskiej książki kucharskiej, in: Silva Rerum, Warszawa: Muzeum Pałacu Króla Jana III w Wilanowie, 7 lutego 2009

- Karol Estreicher: Bibliografia polska, cz. III, vol. XIX, Kraków: Akademia Umiejętności, 1905, p. 355

- Magdalena Herman: Ślady pierwszej polskiej książki kucharskiej, in: Silva Rerum, Warszawa: Muzeum Pałacu Króla Jana III w Wilanowie, 3 grudnia 2020

- Henry Notaker: A History of Cookbooks: From Kitchen to Page over Seven Centuries, Oakland: University of California Press, 2017

- Kazimierz Piekarski: Miscellanea Bibliograficzne: „Kuchmistrzostwo” Macieja Szarffenberga, in: Przegląd Biblioteczny, IV, Kraków: Wydawnictwo Związku Bibljotekarzy Polskich, 1930, p. 415–418

- Marta Sikorska: Smak i tożsamość: Polska i niemiecka literatura kulinarna w XVII wieku, Warszawa: Muzeum Pałacu Króla Jana III w Wilanowie, 2019

- Magdalena Spychaj: „Spis o krmích” z XV wieku: u źródeł czeskiej literatury kulinarnej, in: Przegląd Historyczny, 102/4, 2011, p. 591–607

- Władysław Wisłocki: Przewodnik Bibliograficzny, 14/10, Kraków: nakładem własnym, październik 1891, p. 166–167

- Zygmunt Wolski: Kuchmistrzostwo: Szczątki druku polskiego z początku w. XVI, Biała Radziwiłłowska: nakładem autora, 1891

- Zbiór dla kuchmistrza tak potraw jako ciast robienia wypisany roku 1757 dnia 24 lipca, ed. Jarosław Dumanowski, Switłana Bułatowa, Warszawa: Muzeum Pałacu Króla Jana III w Wilanowie, 2021

- Jarosław Dumanowski, Switłana Bułatowa: Książka kucharska Rozalii Pociejowej i Ludwiki Honoraty Lubomirskiej, in: Zbiór dla kuchmistrza…, p. 11–112

- Čeněk Zíbrt: Staročeské umění kuchařské, Praha: Stará garda mistrů kuchařů, 1927

| ◀️ Previous | 📜 List of posts | Next ▶️ |

| ⏮️ First | 🎲 Random post | Latest ⏭️ |

- Artur Benis

- Svitlana Bulatova

- Martin do Como

- Stanisław Czerniecki

- Jarosław Dumanowski

- Galen of Pergamon

- Kazimierz Piekarski

- Bartolomeo Platina

- Władysław Wisłocki

- Zygmunt Wolski

- Čeněk Zíbrt

- Kyiv

- Cracow

- Prague

- Warsaw

- Sugar

- Cinnamon

- Carp in aspic

- Rice

- Cream

- Squirrel

- Antiquity

- Middle Ages

- Early Modern Period

- 19th century

- 20th century

- 21st century

- Recipës