Difference between revisions of "Of This Ye Shall Not Eat for It Is an Abomination"

(→Blood) |

|||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | {{data| | + | {{data|5 August 2022}} |

[[File:Stempel koszerności.jpg|thumb|upright|Mirror-flipped picture of a kosher certification stamp from interwar Poland, with the Hebrew word כשר ("kosher").<br>{{small|Oświęcim (Auschwitz) Jewish Museum}}]] | [[File:Stempel koszerności.jpg|thumb|upright|Mirror-flipped picture of a kosher certification stamp from interwar Poland, with the Hebrew word כשר ("kosher").<br>{{small|Oświęcim (Auschwitz) Jewish Museum}}]] | ||

I've been asked by one of the Readers to try and explain what it means that something is or isn't kosher. On this blog, I've been focusing mostly on the history of Polish cuisine, but Jewish cuisine used to develop right next to the Polish one for ages, so naturally there's been a lot of overlap and recipe sharing between the two. Which means that if you want to know more about Polish cuisine, it's good to also learn something about Jewish foodways – and how the Jews' own religion has shaped what they do or do not eat. Prior to the Holocaust, most of the world's Jews and Poles lived in the same country, but Gentile Poles, even back then, had seldom more than only a very superficial idea about the religious rules followed by their Jewish neighbours (and ''vice versa''). Nowadays, this level of familiarity is surely even lower. | I've been asked by one of the Readers to try and explain what it means that something is or isn't kosher. On this blog, I've been focusing mostly on the history of Polish cuisine, but Jewish cuisine used to develop right next to the Polish one for ages, so naturally there's been a lot of overlap and recipe sharing between the two. Which means that if you want to know more about Polish cuisine, it's good to also learn something about Jewish foodways – and how the Jews' own religion has shaped what they do or do not eat. Prior to the Holocaust, most of the world's Jews and Poles lived in the same country, but Gentile Poles, even back then, had seldom more than only a very superficial idea about the religious rules followed by their Jewish neighbours (and ''vice versa''). Nowadays, this level of familiarity is surely even lower. | ||

Revision as of 11:24, 5 August 2022

I've been asked by one of the Readers to try and explain what it means that something is or isn't kosher. On this blog, I've been focusing mostly on the history of Polish cuisine, but Jewish cuisine used to develop right next to the Polish one for ages, so naturally there's been a lot of overlap and recipe sharing between the two. Which means that if you want to know more about Polish cuisine, it's good to also learn something about Jewish foodways – and how the Jews' own religion has shaped what they do or do not eat. Prior to the Holocaust, most of the world's Jews and Poles lived in the same country, but Gentile Poles, even back then, had seldom more than only a very superficial idea about the religious rules followed by their Jewish neighbours (and vice versa). Nowadays, this level of familiarity is surely even lower.

I won't be writing here anything you wouldn't find in a plethora of already existing sources, but these sources may be difficult to understand for people with little prior knowledge of Judaism. So I will do my best to elucidate the topic as clearly as I can, while keeping the number of Hebrew and Yiddish terms to a minimum.

But first, a few notes. Firstly, I'm not a follower of Judaism myself, so this will be an outsider's view of this religion. Secondly, the rules I'll be writing about are quite complex, so this will be only a brief and simplified overview of the principal points. Thirdly, Jews aren't all equally pious, so not all of them respect religious dietary laws and, among those who do, some respect them more strictly than others. Henceforth, when writing about "Jews", I will mean only those Jews who really take these laws seriously. And fourthly, Jews have been dispersed across many countries for centuries and developed different ways of interpreting and obeying their laws depending on where they happened to live. Unless I note otherwise, I will be focusing on culinary habits of Ashkenazi Jews, that is, those of Central and Eastern Europe.

What is the Jewish Religion About?

Polin Museum of the History of Polish Jews in Warsaw

First of all, Judaism is a religion which is very big on obeying commandments. Jews believe in a God who doesn't really care whether someone believes in him. What he's interested in is whether the Jews, a nation he made a special covenant with, respect the law he gave them as part of that deal. What you believe in doesn't matter as much as what you do. The chief source of that law is the Torah, also known as the Pentateuch, that is, the first five books of the Bible (Old Testament). It's not just the famous Ten Commandments chiselled in stone tablets, but all of the various commands and prohibitions the Torah is filled with. Long time ago someone determined there's 613 of them altogether and this is the number that has caught on, even though, when other people later did the counting, they got different results.

Biblical commandments are often quite specific and pertain to various spheres of human life. The problem is that it's a sin to break any of them even inadvertently (of course, sins committed on purpose are even worse). That's why generations of rabbis, or experts in Jewish religious law, came up with extended or additional commandments you have to follow in order to prevent breaking any of the Biblical laws even by accident. Eventually, this broad interpretation was bloated to such an extent that it made everyday life almost impossible. And so, in the subsequent stage, the rabbis devised a collection of loopholes to bypass these additional commandments, allowing the Jews to lead relatively normal lives while keeping God happy at the same time. I suppose it explains why the Jews are such a creative people. In any case, we will be seeing here, time and again, the same cycle of: simple Biblical commandment → broad rabbinical interpretation → inventive ways of circumventing it.

Animals, Clean and Unclean

Anyone who knows anything about Jewish dietary laws is most likely aware that Jews are not allowed to eat pork (which doesn't prevent some Polish grocers and restaurateurs from offering things like "schab po żydowsku", or "pork loin in the Jewish style"). But the matter is a tad more complex.

Kashrut, or the set of Jewish food-related religious regulations, is primarily concerned with determining what is "clean", or kosher (and thus edible), and what is "unclean", or treif. The distinction applies mostly to animal species.

Quadrupeds

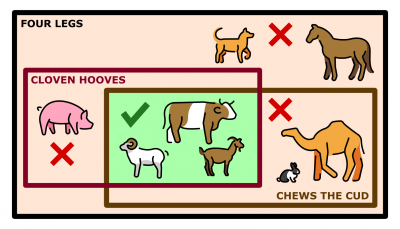

Let's start with four-legged land animals and see what the Bible has to say about their "cleanness".

| Thou shalt not eat any abominable thing. These are the beasts which ye shall eat: the ox, the sheep, and the goat, the hart, and the roebuck, and the fallow deer, and the wild goat, and the pygarg, and the wild ox, and the chamois. And every beast that parteth the hoof, and cleaveth the cleft into two claws, and cheweth the cud among the beasts, that ye shall eat. |

| — Deuteronomy, chapter 14, verses 3–6; in: Authorized (King James) Bible, Bible Gateway |

So, for a land-dwelling mammal to be kosher, it must meet two conditions at the same time: it must chew its cud (which means swallowing its food, partly digesting it in one of its stomachs, regurgitating it back to its mouth, then chewing it well, swallowing again and completing the digestion in the remaining stomachs) and have cloven, that is even-numbered, hooves.

And so, for example, a pig has cloven hooves, but doesn't chew its cud, which is precisely why it's not kosher. A camel, on the other hand, does chew its cud and it does have two toes on each foot, but the toes end with toenails rather than hooves, which makes the camel treif as well. A rabbit also passes its food twice through its digestive system, but obviously has no hooves, so it's out. The only animals which do meet both criteria belong to the suborder Ruminantia, to use modern taxonomic terminology. Apart from the species listed in the Biblical passage above, ruminants also include such creatures as: water buffalo, mouse-deer, bison, moose, wapiti and giraffe. But if we only count those ruminants which are traditionally raised for meat in Europe, then we're left with nothing but cattle, sheep and goats.

I should note here that the notion of ritual cleanness has nothing to do with whether a particular animal is physically clean or dirty. Ritual cleanness isn't a moral category either, so it's not like "clean" animals are good and the "unclean" ones are evil. All animals, as God's creations, deserve the same kind of respect from humans. The only difference is that some of them are considered fit for Jewish consumption, while others are seen as kind of… gross.

Water Creatures

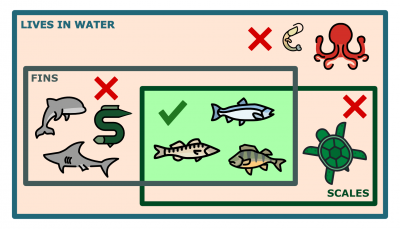

What about aquatic animals?

| These shall ye eat of all that are in the waters: whatsoever hath fins and scales in the waters, in the seas, and in the rivers, them shall ye eat. And all that have not fins and scales in the seas, and in the rivers, of all that move in the waters, and of any living thing which is in the waters, they shall be an abomination unto you. |

| — Leviticus, chapter 11, verses 9–10; in: Authorized (King James) Bible, Bible Gateway |

Again, there are two conditions that must be met at the same time: a water animal ought to have both fins and scales to be kosher. This means that Jews can enjoy many popular fish species, such as herring, salmon, cod, tuna or pike. One should be careful with carp, as some varieties have no or very few scales. To be sure, rabbis have specified that a fish must have at least three scales, so count them when in doubt. What's more, the scales must be visible with a naked eye and easily removable without tearing the skin, which makes such fish as eel, sturgeon and shark unkosher. And anything that lives in water, but is not a fish, that is, all kinds of non-fish seafood, isn't kosher either.

Now, have you heard of a traditional delicacy, still popular in Poland, known as "Jewish caviar"? Is Jewish caviar even possible? Anything that comes from an unclean animal – meat, milk, eggs, etc. – is unclean. So don't be fooled: if the sturgeon isn't kosher, then neither is sturgeon roe. Jewish "caviar" is nothing more than fried goose liver that has been chopped so finely it kind of resembles caviar – in the way it looks, at least, because it certainly doesn't taste the same.

Birds

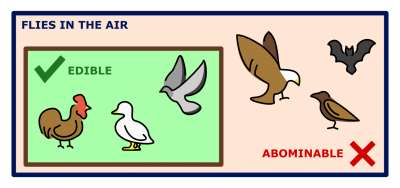

While we're talking about geese, let's take a look at winged animals in general. This is what the Scripture says about flying vertebrates, that is, birds and bats:

| And these are they which ye shall have in abomination among the fowls; they shall not be eaten, they are an abomination: the eagle, and the ossifrage, and the ospray, and the vulture, and the kite after his kind; every raven after his kind; and the owl, and the night hawk, and the cuckow, and the hawk after his kind, and the little owl, and the cormorant, and the great owl, and the swan, and the pelican, and the gier eagle, and the stork, the heron after her kind, and the lapwing, and the bat. |

| — Leviticus, chapter 11, verses 13–19; in: Authorized (King James) Bible, Bible Gateway |

No more clear-cut criteria here. Instead, we've got a short list of bird species which are definitely not kosher. It would seem the matter is simple enough: if these few birds are not kosher, then all other kinds of birds must be good to eat, right? The trouble is that there's no certainty whether all of the bird species enumerated in the original Hebrew text have been correctly translated and identified. Rabbis, therefore, took it upon themselves to come up with their own criteria allowing to classify each bird as either kosher or treif.

They had no doubt about all birds of prey being unclean. When it came to other birds, they were looking at such characteristics as the presence of a backward-pointing toe, a kind of pouch in the gullet and a special sort of stomach lining. But in the end they decided that if Jews had always been consuming a particular species of bird, then this bird must have been kosher, and if they hadn't, then it wasn't. In practice, those birds which are commonly raised as poultry, such as chickens, ducks, geese, pigeons, etc., are all kosher. Turkey, which comes from North America, is a special case, because Jews only learned about its existence once the Spaniards discovered the New World, so there was no long-standing tradition of its consumption to speak of. But the rabbis figured the turkey was similar enough to well-known species of poultry that it's okay to eat it as well.

Creeping Things

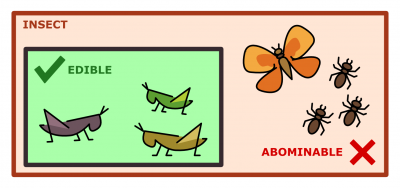

What remains are all the little critters the Bible refers to generically as "creeping things". This term seems to include all invertebrates, as well as amphibians, reptiles and small mammals. The matter of their ritual cleanness is simple enough: they're all unkosher.

| These also shall be unclean unto you among the creeping things that creep upon the earth; the weasel, and the mouse, and the tortoise after his kind, and the ferret, and the chameleon, and the lizard, and the snail, and the mole. |

| — Leviticus, chapter 11, verses 29–30; in: Authorized (King James) Bible, Bible Gateway |

There is one interesting exception, though: the Bible enumerates four kinds of Middle Eastern grasshoppers which are not "abominable".

| Yet these may ye eat of every flying creeping thing that goeth upon all four [sic!], which have legs above their feet, to leap withal upon the earth; even these of them ye may eat; the locust after his kind, and the bald locust after his kind, and the beetle after his kind, and the grasshopper after his kind. But all other flying creeping things, which have four feet, shall be an abomination unto you. |

| — Leviticus, chapter 11, verses 21–23; in: Authorized (King James) Bible, Bible Gateway |

Again, it's hard to tell which species exactly Biblical authors had in mind, so there's no other choice then falling back on tradition. But when it comes to tradition of locust consumption, it turns out it's only been preserved among Yemenite Jews. They're the only ones who can still tell which species of these insects are kosher. As for European Jews, just like Europeans in general, they're happy not to include any kinds of bugs in their menu.

Sometimes, however, you may consume some invertebrate-derived ingredients without knowing it. You may not think about it on an everyday basis, but black pasta owes its colour to sepia, which is extracted from a cuttlefish ink sac, while some strawberry milkshakes are red, because they contain cochineal, a crimson dye obtained from parasitic scale bugs feeding off cactuses. That's why there are special Jewish organizations issuing kosher certifications. It's their job to verify that all ingredients of a given food item are ritually clean and the entire production process is in line with Jewish dietary laws.

And what about honey? It can't possibly be kosher, it would seem. But there's good news here: in the past, people thought honey was produced by flowers and all that bees were doing was collecting and storing it. From Jewish perspective, honey is a perfectly vegan food rather than an detestable insect secretion. Except honeydew honey, that is; in this case it was impossible not to notice that bees collected it not from flowers, but from aphids' butts.

Blood and Other Tissues

An animal may be ritually clean, but that's not the end. It still needs to be properly killed and dressed for it to be kosher. This is mostly related to one of the most important commandements in Jewish law, wich is the prohibition against consumption of blood.

Blood

| And whatsoever man there be of the house of Israel, or of the strangers that sojourn among you, that eateth any manner of blood; I will even set my face against that soul that eateth blood, and will cut him off from among his people. For the life of the flesh is in the blood: and I have given it to you upon the altar to make an atonement for your souls: for it is the blood that maketh an atonement for the soul. […] And whatsoever man there be of the children of Israel, or of the strangers that sojourn among you, which hunteth and catcheth any beast or fowl that may be eaten; he shall even pour out the blood thereof, and cover it with dust. For it is the life of all flesh […] |

| — Leviticus, chapter 17, verses 10–11 and 13–14; in: Authorized (King James) Bible, Bible Gateway |

Blood symbolizes life, and the giver of all life is God. That's why blood is sacred and, in a way, reserved for God alone. Back when the Temple in Jerusalem still stood (ultimately demolished by the Romans in 70 CE), the Temple's altar was regularly sprinkled with calf or lamb blood as a sacrifice of atonement. And since the blood was meant as a gift for God, it was off-limits to humans. Hence, the strict and oft-repeated Biblical ban on drinking blood. When broken, it was punishable by God himself setting his face against the perpetrator: I see you, see what you did, and won't forget it.

Considering how strong the taboo against blood consumption in Judaism is, it's hard to understand how it was possible for Christians throughout Europe and over many centuries to believe an absolutely dumb and vicious gossip about Jews using Christian children's blood for making matzah. In Poland, some monarchs attempted to suppress it. As early as in 1264, Duke Boleslav the Pious of Greater Poland issued a famous charter of Jewish privileges, known as the Statute of Calisia (Kalisz), whose article 30 explicitly forbade anyone from spreading the spiteful rumour. Seventy years later, King Casimir the Great extended the law from the province of Greater Poland to the entire Kingdom of Poland. But despite these efforts, the canard continued to serve as an excuse for anti-Jewish pogroms for centuries, including the particularly shameful post-Holocaust Kielce Pogrom of 1946.

What does the prohibition against blood consumption mean in practice? Well, the animal must be butchered in such a way that lets it bleed out as quickly and as amply as possible, and then the carcass must be dressed in a way that will remove almost all of the remaining blood. This so-called Jewish ritual slaughter is practised by specially trained butchers who are required to cut the animal's throat with a single move of a long, very sharp, unserrated knife, severing the wind pipe, the food pipe and major blood vessels at the same time. Next, the carcass is quartered, larger blood vessels are removed, the meat is soaked in water, buried in salt and rinsed with water again, so as to get rid of the last drops of blood. The liver, which is especially well supplied with blood, must be additionally grilled.

The prohibition also applies to that little red spot you may occasionally find inside an egg. It's usually a tiny blood clot, which may result from a small rupture of a blood vessel in the hen's oviduct. And if it's blood, then it's unkosher. That's why each egg must be cracked into a glass and checked for such clots before use. If a blood spot is found, it must be removed (some Jews discard the entire egg). Okay, but what about a boiled egg? You can't see the blood spot when the white is already thickened, so it would seem that a boiled egg can't be kosher. But here's a surprise: if you can't see it, then it's fine, so soft or hard-boiled eggs are good to eat. Of course, if you do find a blood spot inside a boiled egg, then you have to remove it (or even throw away the whole egg).

Knowing what you already know about kosher cookery, you may be surprised to know that there is such thing as a Jewish kishke. Especially, if you know what its ancestor, the Polish kiszka, is: a thick sausage made of pork offal mixed with buckwheat and pork blood, and stuffed into a pork intestine ("kiszka" literally means "bowel" in Polish). You'd be hard pressed to find anything less kosher than that! And yet, Polish Jews have been able to invent their own kosher version of this delicacy. They've done this by replacing the blood with goose fat, the buckwheat with flour, seasoning the mixture generously with onions and packing it all inside a beef intestine.

Ritual Slaughter Controversy

Let me return to the question of ritual slaughter, as it's a topic capable of arousing quite strong passions. In Poland (and not only), it's been raised from time to time since before World War 2. Two viewpoints are at loggerheads here: on the one side, the right of the Jews to practice their religion; on the other, the right of animals to a humane death. And also the right of farmers and the meat-processing industry to make loads of money (about 30% of the beef exported from Poland is either kosher of halal; Muslim ritual slaughter is quite similar to the Jewish one). That makes three viewpoints actually. Animal rights advocates maintain that an animal subjected to ritual slaughter without prior stunning may agonize for up to several minutes before it finally dies. What's more, in some Jewish butcheries, animals are turned upside down before they are killed; while it makes the death quicker, it also increases the level of stress prior to death. On the other hand, for meat to be kosher, the slaughtered animal must be in good health (no major injuries and no defects in internal organs; lungs are particularly closely examined after the slaughter) and conscious. And this rules out stunning.

Ritual slaughter advocates respond that the requirement for the animal to be healthy and uninjured makes it necessary to treat it humanely on the farm, in transport and at the abattoir. They also claim that a creature slaughtered by an appropriately trained ritual butcher dies in a matter of seconds and practically without pain (keep in mind, though, that this said by people who subject their own newborn sons to genital mutilation without anaesthesia). Ritual slaughter, the argument goes, is at least as humane as slaughter with prior stunning (which may be painful in and of itself), to say nothing of such practices as hunting or carrying live carp in a plastic bag without water (which are legal and common in Poland). The debate is complicated by the fact that any attempts at limiting the practice of ritual slaughter are met with knee-jerk accusations of anti-Semitism (before World War 2, this was indeed done to deliberately annoy the Jews).

The most recent rounds of the conflict around ritual slaughter in Poland took place within the 21st century. According to the Polish Animal Welfare Act of 1997, "a vertebrate animal may be slaughtered in an abattoir only after prior deprivation of consciousness".[1] The same law originally contained a special provision, excepting those animals which were subjected to "specific methods of slaughter prescribed by religious rites".[2] This exemption, however, was cancelled by parliament in 2002,[3] ostensibly to bring Polish legislation in line with European Union law (even though the EU allows individual member states to make their own rules regarding ritual slaughter). Two years later, in an attempt to save lucrative Polish kosher and halal meat exports, the agriculture minister issued an ordinance which brought the exemption back,[4] but in 2012, the Constitutional Tribunal struck it down. This prompted foreign Jewish press to raise an alarm: a Polish court has ruled ritual slaughter unconstitutional! Mr. Michael Schudrich, Chief Rabbi of Poland, himself a vegetarian, expressed a more nuanced view, saying there's no point fighting over which way of killing is better.[5] In reality, the Tribunal's ruling was only based on procedural grounds: a ministerial ordinance must not contradict an act of parliament.[6] A new act of parliament would have been enough to legalize ritual slaughter again, but a bill to that effect was voted down in parliament in 2013. Eventually, the case was brought back before the Constitutional Tribunal in 2014; this time around, the Tribunal analysed the Animal Welfare Act itself and ruled that a complete ban on ritual slaughter was incompatible with constitutional guarantees of religious freedom.[7] Polish Jews breathed a sigh of relief and Polish meat lobby probably breathed an even bigger one. In 2020, Chairman Jarosław Kaczyński tried once more to limit the scale of ritual slaughter, so that it would be only legal when performed for the needs of local (and rather small) Jewish and Muslim communities, but not for export.[8] But even Poland's virtual dictator was defeated by Poland's Big Meat in the end.

Adipose Tissue and the Sciatic Nerve

The blood prohibition applies to all land animals (fish blood is kosher, which doesn't mean Jews drink it by the glassful). When it comes to farm mammals (cattle, sheep and goats), though, there are still more limitations. Firstly, eating their suet, or fat covering certain internal organs, is forbidden. Just like blood, it used to be reserved for the sacrifices offered in the Temple. Jews believed that God found the stench of burning animal fat particularly pleasant.

| And he shall offer of the sacrifice of the peace offering an offering made by fire unto the Lord; the fat that covereth the inwards, and all the fat that is upon the inwards, and the two kidneys, and the fat that is on them, which is by the flanks, and the caul above the liver, with the kidneys, it shall he take away. And Aaron’s sons shall burn it on the altar upon the burnt sacrifice, which is upon the wood that is on the fire: it is an offering made by fire, of a sweet savour unto the Lord. |

| — Leviticus, chapter 3, verses 3–5; in: Authorized (King James) Bible, Bible Gateway |

The above passage is only about bovine suet, but sheep and goat fat is covered by similar regulations.

And then there's probably the weirdest prohibition of them all: Jews are not allowed to eat a string that goes down all along the thigh and if it's damaged, then you can't move your hind limb. This commandment is linked to a Biblical story about an injury suffered by Jacob Israel while sparring with some mysterious figure when there was no one else around (kind of like Brad Pitt's character in Fight Club). The key word in the passage below has been translated as "sinew", but what it's really about is the sciatic nerve.

| And Jacob was left alone; and there wrestled a man with him until the breaking of the day. And when he saw that he prevailed not against him, he touched the hollow of his thigh; and the hollow of Jacob’s thigh was out of joint, as he wrestled with him. […] And as [Jacob] passed over Penuel the sun rose upon him, and he halted upon his thigh. Therefore the children of Israel eat not of the sinew which shrank, which is upon the hollow of the thigh, unto this day: because he touched the hollow of Jacob’s thigh in the sinew that shrank. |

| — Genesis, chapter 32, verses 24–25 and 31–32; in: Authorized (King James) Bible, Bible Gateway |

This legend was obviously composed in ancient times for the purpose of explaining an even older and already obscure taboo. What was the original rationale for not eating the sciatic nerve? Nobody knows. What is known is that removing the nerve along with the fat, which tends to grow into the muscle tissue especially in the hind half of the animal, is possible, if done by a skilled butcher, but it's time-consuming and unprofitable on a larger scale. Which is why Jews, traditionally, eat meat solely from the front half of the animal. Their Gentile neighbours have been taking advantage of this tradition for centuries, buying the appetizingly marbled hind meat from Jewish butchers at half price.

| The reason why meat is so cheap [in September] is that Jews, who slaughter a lot of cattle before their almost month-long festivals, make all of their profit on the kosher, while selling the treif, as well as hind quarters of meat, which they do not eat, for a song. | ||||

— Anna Ciundziewicka: Rocznik gospodarski, Wilno: Drukarnia Gubernialna, 1854, p. 137, own translation

Original text:

|

Bird fat is kosher, which is why well-fattened geese have been so important in traditional Jewish cuisine. Schmaltz, or rendered goose fat, has long been the primary Jewish substitute for pork lard and beef suet, especially that Jews are not allowed to fry their meat in butter (I will explain in a moment). Hence, geese were generally seen as a typically Jewish kind of poultry. Nobody expects the Spanish Inquisition! Yet anyone who got caught eating goose meat in 17th-century Spain may have expected the Spanish Inquisition to charge them with the crime of secretly being a Jew.

Meat and Dairy

Another prohibition which severely restricts what and when Jews may eat also comes from the Torah, which says:

| Thou shalt not seethe a kid in his mother’s milk. |

| — Exodus, chapter 34, verse 26; in: Authorized (King James) Bible, Bible Gateway |

Just to be clear, the word "kid" is used here in its original sense of "young goat" and not "human child". Of course, one shouldn't take this literally anyway. It's not just about young goats, but any meat in general (including poultry). And it isn't just about the animal's own mother's milk, but any kind of milk. And not just seething (boiling), but any kind of thermal treatment. Just in case, one should never eat any kind of meat together with any kind of dairy products. What do they mean by "together", though? Certainly not as part of the same meal. But what if a piece of meat is stuck between someone teeth after the meal? You never know, so just in case, you must wait six hours after eating meat before you can have anything dairy. And if you'd been having cheese, then you have to wait six hours until you can enjoy meat again.

Before eating or drinking anything, a Jew must first establish which of the following three categories of food that thing belongs to: meat, dairy or neutral. Neutral foods are those that you can eat together with either meat or dairy (but not with both at the same time, obviously). These include all plant-based products (including honey), as well is inorganic aliments, like water and salt. Eggs and fish are neutral as well, although rabbis advise against eating fish together with meat anyway. Bread, as a basic staple, must always be neutral, so kosher bread should never contain milk or butter.

Some rabbis have classified certain animal-based foodstuffs, such as gelatin or rennet, as neutral, although it must have required some impressive mental acrobatics on their part. Gelatin is made from skin and bones, that is, these body parts which are not normally considered fit for human consumption. And the rules of kashrut are only concerned with food, so they don't apply to anything that's inedible. Same thing with rennet, an enzyme obtained from a calf's stomach and used in the production of most yellow cheeses. Pure dried rennet doesn't resemble meat in any way and no one in their right mind would eat it. So it seems we're good. But on the other hand, gelatin and rennet are added to food, which means they are edible after all. But then, you only add very small amounts, and very small amounts of things unkosher are sometimes permissible when mixed with large amounts of kosher stuff. But on the fourth hand, this rule only applies, if the small amount of the unkosher additive doesn't affect the overall characteristics of the whole product; and the whole point of using gelatin or rennet is that we want them to affect the overall characteristics of the whole product… And so on, and so forth. In the end, the more liberal Jews will probably partake of rennet-set cheese or jelly cheesecake (provided, of course, that the rennet or the gelatin comes from kosher animals butchered in a kosher way). Those more strict will rather look for plant-based or microbiological equivalents.

What's more, meat products should never even touch the dairy ones. Not even indirectly. A vessel that has been "stained" with milk fat can no longer be used for meat – and vice versa. That's why a typical kosher kitchen is really two or even three kitchens rolled into one: separate sets of milk, dairy and neutral dishes, separate sets of utensils, pots, pan, kitchen tools, towels, separate cupboards, worktops, fridges, stoves, microwave ovens, sinks and dishwashers. Preferably with some kind of colour coding, so that nobody ever chops an onion that is meant for a dairy dish on a meat cutting board by mistake.

You can see how important this separation of meat and dairy in Judaism is by how the Jews observe the Feast of Weeks (Shavuot), when they remember how God (through Moses) gave them a new law. According to tradition, all of the law was revealed at once, which means that Jews had to adapt to a completely new way of life overnight. Until then, they had used the same pots for both meat and dairy, just like everyone else. Now they had to kasher their pots (by rinsing with boiling water) and decide whether they would use them for meat or for dairy moving forward. On the first day of the new law they didn't have any kosher-slaughtered meat yet anyway, so they chose to use all of their old pots as dairy pots and later make new vessels for cooking meat. And so, on the first day, they could only eat dairy, but no meat. In memory of that, Jews celebrate the Feast of Weeks by having their favourite dairy-based dishes, such as milchik borscht (vegetarian red-beet soup whitened with cream) and blintzes (crêpes filled with sweetened farmer cheese and sautéed until golden).

That's all for now, but it's not the end of the topic. Stay tuned for my next post, where I will delve into, among other things, which religious commandments gave rise to such Jewish classics as cholent, gefilte fish and matzah balls.

References

- ↑ Ustawa z dnia 21 sierpnia 1997 r. o ochronie zwierząt [Animal Welfare Act of 21 August 1997] (Dz.U. 1997 Nr 111 poz. 724), article 34, point 1

- ↑ Ustawa z dnia 21 sierpnia 1997 r. o ochronie zwierząt [Animal Welfare Act of 21 August 1997] (Dz.U. 1997 Nr 111 poz. 724), article 34, point 5 (nullified)

- ↑ Ustawa z dnia 6 czerwca 2002 r. o zmianie ustawy o ochronie zwierząt [Animal Welfare Amendment Act of 6 June 2002] (Dz.U. 2002 nr 135 poz. 1141), article 1, point 27 (b)

- ↑ Rozporządzenie Ministra Rolnictwa i Rozwoju Wsi z dnia 9 września 2004 r. w sprawie kwalifikacji osób uprawnionych do zawodowego uboju oraz warunków i metod uboju i uśmiercania zwierząt [Ordinance of the Minister of Agriculture and Rural Development of 9 September 2004 on the qualifications of persons authorised to conduct professional animal slaughter and on conditions and methods of killing animals] (Dz.U. 2004 nr 205 poz. 2102), paragraph 8, point 2

- ↑ Michael Schudrich, quoted in: Piotr Pacewicz: Schudrich: Nie licytujmy się, jaki sposób zabijania jest najlepszy, in: Krytyka Polityczna, 18 July 2013

- ↑ Wyrok Trybunału Konstytucyjnego z dnia 27 listopada 2012 r. [Constitutional Tribunal Ruling of 27 November 2012], file no. U 4/12 (Dz.U. 2012 poz. 1365)

- ↑ Wyrok Trybunału Konstytucyjnego z dnia 10 grudnia 2014 r. [Constitutional Tribunal Ruling of 10 December 2014], file no. K 52/13 (Dz.U. 2014 poz. 1794)

- ↑ Poselski projekt ustawy o zmianie ustawy o ochronie zwierząt oraz niektórych innych ustaw [Animal Welfare Amendment Bill] (Druk nr 597), article 34, point 13 (a)

Bibliography

- Jacob Cohn: The Royal Table: An Outline Of The Dietary Laws Of Israel, New York: Bloch Publishing, 1936

- Laws of Religion: Laws of Judaism Concerning Food, in: Laws of Religion: Judaism and Islam, Religion Research Society

- Tracey R. Rich: Kashrut: Jewish Dietary Laws, in: Judaism 101

- Gil Marks: Encyclopedia of Jewish Food, Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, 2010

| ◀️ Previous | 📜 List of posts | Next ▶️ |

| ⏮️ First | 🎲 Random post | Latest ⏭️ |